The Charles W. Capps Jr. Archives and Museum, which sits on the campus of Delta State University in Cleveland, Mississippi, is named, like a number of buildings at DSU, after a state political figure who needed to be thanked. The structure’s handsome white façade aspires to something classic and grand, with the entrance’s square columns suggesting that perhaps some of democracy’s great secrets lie within.

The most prominent and voluminous of all the manuscript collections at the archives is that of Walter Sillers Jr. (1888-1966) of the nearby Mississippi River town of Rosedale. Sillers was a lawyer, cotton planter, and, at 22-plus years, the longest-serving Speaker of the Mississippi House of Representatives. His half-century tenure in the House, from 1916 to 1966, is also a record. Perhaps remembered for his staunch defense of racial segregation in the later stages of his career, Sillers was also “Mr. Delta” in state politics for decades, fiercely championing the interests of his home region.

Two schools

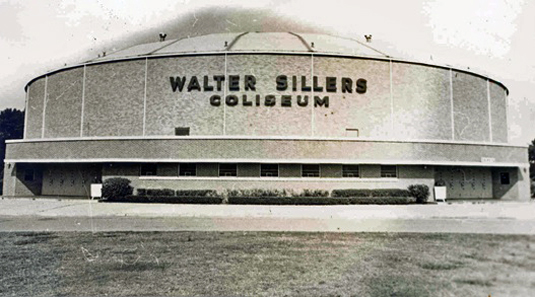

Sillers was Delta State’s key patron and longtime protector in the legislature, especially in its early years as a small teachers college during the Great Depression of the 1930s. As a result of his years of advocacy, he has his own Delta State building dedicated in gratitude, the Walter Sillers Coliseum.

Sillers’ reign as House Speaker, from the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s, coincided with the most dramatic period of Mississippi’s civil rights struggle. In leading the White response, he was more subtle than his political rival, Theodore G. Bilbo, and operated locally and more behind-the-scenes than his nationally known Delta neighbor U. S. Senator James O. Eastland. But as a longtime tactician and powerbroker on behalf of the “Southern way of life,” at least at the state level, Sillers was more than the equal of his two higher-profile colleagues.

For example, in the years prior to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision by the U. S. Supreme Court outlawing public school segregation, pressure was building to integrate Delta State, along with the other Whites-only Mississippi campuses. To forestall that possibility and help redirect the expected number of Black applicants, Speaker Sillers took the lead in the legislature in founding (and funding) Mississippi Vocational College outside Itta Bena in Leflore County. The intention was that African Americans would settle for going there instead and would seek an education strictly to acquire a blue-collar trade, or to train for teaching. In strategic appreciation of the legislative largesse, that school, since renamed Mississippi Valley State University, put up a Sillers structure too – the Walter Sillers Fine Arts Building – on a campus now traversed by a Medgar Evers Street, a Fannie Lou Hamer Street, and a Rosa Parks Avenue. Mississippi’s racial history, it would seem, is not all that simple.

Bolivar County heritage

Walter Sillers Jr. was born April 13, 1888, into a landholding Bolivar County family with extensive political connections. The Mississippi River was literally a backdrop of his life. His family settled in a large Victorian house on Levee Street in Rosedale, a site abutting the river’s embankment, and later as an adult Sillers made his own home on the same street. He also grew up with family ties both to the American Civil War and to the overthrow of Reconstruction Republican rule. His grandfather, Joseph Sillers, had been a Confederate soldier and was captured at Vicksburg; he died in 1865. Sillers’ father, Walter Sillers Sr., had taken part in the revolution of Democrats in 1875, which restored White governance in Mississippi. His father was also a lawyer, owner of several plantations in Bolivar County, member of the state Democratic executive committee, and for a time held the most powerful political job in the Mississippi Delta – chairman of the state levee board.

Sillers went to the University of Mississippi and by his early twenties was practicing law back in Rosedale with his father. The law office would remain for Sillers the seat of his local power for the rest of his life. He first entered the Mississippi Legislature in 1916 as a “whisker-less” 27-year-old. (“Whisker-less” was a lighthearted term the newspapers of the day used to underscore the state capitol newcomers’ distinctive clean-shaven style and their relative youth.) His arrival coincided with Bilbo’s first term as Mississippi governor, which was the high point of Progressivism in the state. Mississippi was in transition in the late 1910s and the new cohort of young state lawmakers, also including future governors Mike Conner and Thomas L. Bailey, seemed to herald a new day. Though Sillers came to the capital city of Jackson to represent the cotton planters of his home area, there were some traces of reform in his early public profile.

Accumulating power

Sillers was a pro-labor lawyer. As late as 1931, he still had his workingman credentials intact as the attorney for the American Federation of Labor in the state and as an honorary union member. Several years later, a flyer announcing a Sillers speech touted him as “long an advocate of progress – exponent of agriculture, education, roads and community health.” But Sillers’ brand of progressivism, such as it was, differed sharply from the more classic anti-corporate strain. He was part of a group, in ascendance in Mississippi politics by the mid-1920s, of so-called “business progressives,” which sought gradual, mild, controlled reform without upsetting the state’s existing economic and social structure.

As the 1930s wore on with the expansion of the federal New Deal and then into the early 1940s, Sillers’ power accumulated and his record and public statements were increasingly marked by business conservatism and defense of the embattled prerogatives of his race. His hardening political outlook came to include: resentment toward U. S. President Franklin Roosevelt and the national Democratic Party over revocation of the two-thirds rule, which for nearly a century had essentially given the White South a veto over party nominees; manipulation of New Deal land-purchasing programs in the Delta for his own personal financial gain; misgivings about industrialization for Mississippi; alarm over two large biracial cooperative farms formed in the Delta; opposition to Governor Paul B. Johnson Sr.‘s “little New Deal” for Mississippi in 1940; a growing preoccupation with anything that might be construed as associated with communism or socialism; fury at the 1944 Smith v. Allwright U. S. Supreme Court ruling banning the all-white political primary, one of the key tools propping up White supremacist power; support for the poll tax; and a deeply suspicious if complicated stance toward the federal government generally.

In the early 1940s, Sillers served as president of the Delta Council, the inner sanctum of the business community in the state’s cotton-growing region. The 1940s and 1950s Mississippi media regularly referred to Sillers, now at the pinnacle of his legislative power, as the “Old Guard” or the “Grand Old Gibraltar” or the “Old Man River” (for his faithful attention to levee improvements). Sillers’ ongoing combination of defense of White racial privilege and advocacy for Delta business interests came to define his tenure in office.

Civil rights

By the late 1950s and the 1960s, now in his final years and slowed by a heart attack, Sillers’ ever-more strenuous efforts to stave off change to the racial status quo reflected the extreme polarity of the intensifying civil rights crisis in Mississippi. He was an active member of the Sovereignty Commission, the state government’s last-ditch effort against integration. His best-remembered quotation was aimed at moderate Greenville newspaper editor Hodding Carter, who, Sillers said, was “unfit to live in a decent white society.” His campaign press releases were addressed to “White Democrats of Bolivar County.” In the wake of the Brown ruling, Speaker Sillers was a moving force behind a constitutional amendment allowing the closure of the state’s public schools if necessary to preserve segregation.

Though Sillers never held public office beyond the Mississippi House of Representatives, his influence was felt regionally if not nationally on resisting progress on civil rights. He had a central role in the States’ Rights Democratic Party (the Dixiecrats), most notably in 1948. In February of that year, U. S. President Harry Truman sent a special message to Congress urging implementation of his civil rights committee’s recommendations. Sillers, leading a group of other state lawmakers, wired a fervent reaction to Mississippi’s U. S. House of Representatives delegation in Washington. “We join with all the white Democrats in Mississippi who appreciate your forthright, outspoken denunciation of the president’s message and the damnable, communistic, unconstitutional, anti-American, anti-Southern legislation recommended to Congress,” the telegram stated. “We commend you for your courageous defense of the South.”

Apart from racial issues, Sillers had an impressive shrewdness and ubiquity as a political operator. Nobody stays in public office for more than half a century without highly developed political judgment, but Sillers’ meticulous approach and attention to constituent service, to patronage, to ongoing Mississippi political developments, to the convoluted process of making law, and to his law practice, all give evidence of a uniquely gifted mind harnessed to dogged work habits. The depth and breadth of his experience in Mississippi law and politics was unsurpassed. He was steeped in the details of complex issues such as insurance, taxes, procurement, agricultural allotments, pensions, land assessment, railroad freight rates, and the implementation of the U. S. Census in Mississippi. With his many years in the House, including a stint as chairman of the Rules Committee, Sillers also thoroughly understood the nuance and arcana of legislative procedure and this expertise gave him still added authority. He either chaired or sat on many influential boards, commissions, and committees – including the State Building Commission and the Legislative Planning Committee.

A related point is how divided and localized political power was in Mississippi during Sillers’ time, and the capacity for skilled persistent leadership required to make it all function effectively. The Mississippi House of Representatives of the 1940s, for example, had as many as forty-two separate committees. There was a committee on drainage, another on fees and salaries, one on the oyster industry, and even one on “humane and benevolent institutions.” There were committees on public health, public land, and public work. There was a committee on interstate cooperation. There was even a committee on “unfinished business.” And so on. Someone had to choose and motivate committee members and then coordinate the work of all those separate fiefdoms. For years, that inside political dealmaker and leader was “Mr. Walter,” as his colleagues admiringly addressed him.

As Mississippi grappled with social change in the 20th century, it was the state’s governors in particular who seemed to seize and hold the spotlight of massive resistance. The media characterization of events such as James Meredith’s attempt to enroll at Ole Miss in 1961-62 underscored the dramatic role of memorable figures such as Governor Ross Barnett. But, aside from the theatrics, as riveting as they were, the governor’s office actually had limited relevance and influence when compared with the Mississippi Legislature. Governors were term-limited and their office budgets were intentionally kept meager. With one-party (Democratic) rule, the governor’s leverage in lawmaking was minimal. By contrast, the actions of members of the legislature, and in particular those of the oligarchy of old-timers such as Sillers who tightly controlled it, were crucial. Karl Wiesenburg, a state representative from Pascagoula in the late 1950s and early 1960s, speaking in 1965, stated: “Mr. Sillers has been for some thirty years the most important man in the state of Mississippi. Governors may come and go, but Mr. Sillers goes on forever.”

Benjamin O. Sperry, Ph.D., is an instructor in history at Cleveland State University and Lakeland Community College, both in Ohio. He spent the 2009-2010 academic year as a visiting professor of history at Delta State University.

-

Walter Sillers Jr. was first elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives in 1916. Courtesy of Delta State University Archives & Museum, M004_BP1_F5d. -

Speaker Sillers presides over the Mississippi House of Representatives, date unknown. Courtesy of Delta State University Archives & Museum, M004_BP1_F5a.

-

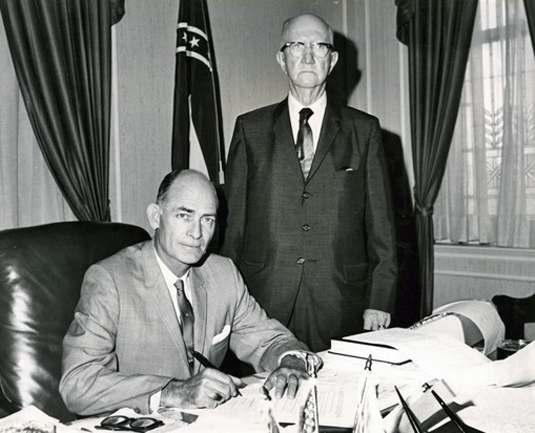

Sillers stands behind Governor Paul B. Johnson Jr. as he signs act repealing statewide prohibition in 1966. Courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/POL/1983.0013/1. -

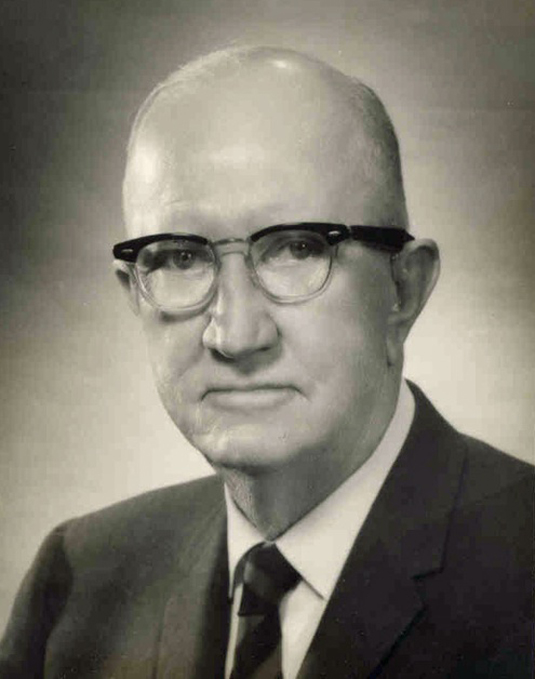

Walter Sillers in 1960. Courtesy of Delta State University Archives & Museum, M004_BP1_F5c. -

The Walter Sillers Coliseum at Delta State University was completed in 1961. Courtesy of Delta State University Archives & Museum, RG25_B1F36_SillersColiseumF. -

Unveiling of Sillers portrait in the Walter Sillers Building in Jackson, 1972. Mrs. Walter Sillers stands with then Speaker of the House John R. Junkin. Courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/2007.0075/17. -

Walter Sillers Building on High Street in Jackson, Mississippi. Courtesy of Downtown Jackson Partners, Inc.

Resources:

Cobb, James C. The Most Southern Place on Earth: The Mississippi Delta and the Roots of Regional Identity. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Key Jr., V.O. Southern Politics in State and Nation. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1984.

Morgan, Chester M. Redneck Liberal: Theodore G. Bilbo and the New Deal. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1985.

Sillers Jr., Walter, Papers. Charles W. Capps Jr. Archives and Museum, Delta State University.

Wiesenburg, Karl. Interview. Civil Rights Documentation Project, Mississippi Humanities Council, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Millsaps College Archives, June 11, 1965.

Woodward, C. Vann. Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel. New York: Macmillan, 1938.

_________ Origins of the New South, 1877-1913. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, Revised edition, 1971.