Progressivism was a political movement that swept America beginning about 1900. Progressives were people who believed that politicians should combine human compassion with the latest scientific and medical advances in order to tackle tough problems and supply solutions to those problems. Among the most famous Progressives nationally were U. S. presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.

Progressives saw that the United States faced many tough problems: poverty, alcoholism, child labor, inadequate roads, unsafe factories, epidemic diseases, and crowded city housing. Yet even though they spent a lot of their time pondering these problems, Progressives were not at all gloomy because they believed that if government acted intelligently all of these problems could be solved.

Mississippi was first in the nation with two Progressive reforms. The first was aimed at the problem that politicians seemed to have too much power. In Mississippi in the late 19th century, the nominees for governor and other offices had been chosen by other politicians meeting at their party’s state convention. Mississippi became the first state in the nation to bring in primary elections, in which the citizens voted directly to decide who would be the nominee of each political party. Thus this reform in Mississippi, enacted in 1902, took some power away from politicians and gave that power directly to the voters.

The other “first” for the state of Mississippi was its prohibition of alcoholic beverages. Across the United States, many Progressives pointed out the problems of alcoholism, including medical ailments and the difficulty alcoholics experienced in keeping their jobs. In 1908 Mississippi Progressives, helped by many church leaders, secured passage of a law outlawing alcoholic beverages in the state.

Later, the United States Congress passed the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, making Prohibition a nationwide policy. Constitutional amendments must be ratified (approved) by three-quarters of the states, and Mississippi’s Progressives saw to it that their state was the first in the nation to ratify the Eighteenth Amendment.

Child labor

The first governor of Mississippi chosen under the primary election system was James K. Vardaman, elected in 1903. In his campaign speeches Vardaman had supported a number of Progressive causes, and as governor he and the legislature brought in many Progressive reforms.

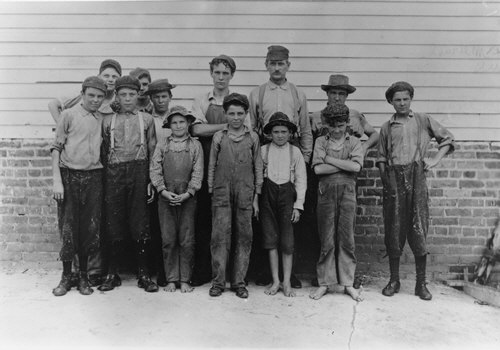

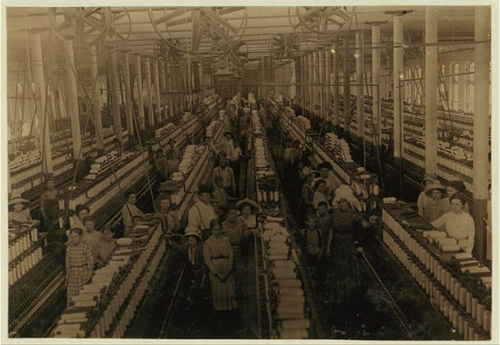

One of the most important Progressive reforms was a 1908 law during the administration of Governor Edmund Noel that made it illegal for factories to hire young children under age 12 to work in factories and established a 10-hour work day and a 58-hour work week. The children under age 12 who had worked in factories would now be able to attend school instead.

Prior to the passage of the 1908 law, factory managers liked to hire children because children worked cheap. In 1896, for example, child textile workers earned an average of 31 cents per day, compared with 47 cents per day for women, and 67 cents for men.

Six years later while Governor Earl Brewer was in office, the legislature raised the work age limit for girls to 14 years, and left the age limit for boys at 12, but limited the work day to eight hours with a 48-hour work week for boys under 16 and girls under 18.

Diseases, convict labor, and roads

Governors Vardaman, Noel, and Brewer helped make sure that state government played a large role in conquering diseases such as pellagra and hookworm. Also while Vardaman was governor, Mississippi began to take steps to end convict leasing, a system where persons convicted of minor offenses had their labor rented out to the highest bidder – a system that in many ways resembled slavery.

Another governor with a Progressive record was Theodore G. Bilbo. Elected in 1915, Bilbo worked with the legislature to secure passage of a number of Progressive laws. For example, Mississippi faced the problem that nearly all of the state’s roads were dirt roads, and when rains came the roads were nearly impassible for automobiles, which were just starting to make an appearance in the state. Under Bilbo’s leadership, the legislature set up the State Highway Commission to help bring better roads to Mississippi. The state opened a juvenile reformatory so teenagers convicted of crimes would not be imprisoned with adult offenders.

While Bilbo was governor the state opened a new charity hospital to provide medical care for poor people who were not able to pay for it. The state also opened night schools to help adults who had not been able to get an education when they were younger.

Nationwide and in Mississippi, Progressivism came to an end around the year 1917. That was the year the United States entered World War I. Progressivism had included some expensive programs for both the state and United States governments, and now with the added expenses of wartime, Progressive programs were often dropped. Also, American newspapers devoted so much space to war news that they stopped giving much attention to Progressive reforms as workplace safety and child labor.

Still, Progressivism was an important movement, and Mississippi seems Progressive in the present day when one notices its two “first in the nation” reforms of the primary election and the Eighteenth (Prohibition) Amendment. Yet in some other ways, Mississippi does not seem so Progressive.

Woman suffrage and race relations

Nationwide, one important part of Progressivism was woman suffrage, which means the right of women to vote. During the early part of the nation’s history, voting had been limited to males only. A handful of states granted women the right to vote in the late 1800s, and with the rise of Progressivism after 1900, the more Progressive states also extended voting rights to women.

Mississippi, however, did not. Several Progressive Mississippians did work for woman suffrage – these included Belle Kearney and Nellie Nugent Somerville. Governors Vardaman and Noel also backed woman's suffrage. The 1919 Mississippi legislature, however, refused to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which brought in nationwide woman suffrage. This action of the legislature suggests Mississippi was not such an important part of Progressivism.

In the area of race relations, Mississippi also seems to lack a Progressive record. Governor Vardaman, for example, despite being Progressive in many ways, was a bitter racist. His method for getting elected to office was to fan the flames of racial hatred, and to warn White Mississippians that only by voting for him could the interests of White people be protected.

Vardaman’s record on the subject of lynching was especially troubling. Lynching was the killing of a person by a mob, usually by hanging. The victims of lynch mobs in Mississippi were almost always Black. In his campaign speeches, Vardaman praised the actions of lynch mobs, and said lynchings were necessary to control Black men. Vardaman claimed that most of the men who were lynched were guilty of raping White women, although in fact this was not true.

The story of Vardaman and lynching becomes more complicated when we note that as governor he did what he could to prevent lynchings. He even traveled to counties where a lynching seemed about to take place, taking with him members of the National Guard who could help ensure that a lynching did not occur. Thus Mississippi had a governor who got elected by praising the practice of lynching, but who by his actions worked against it.

Even if Vardaman quietly worked against lynching, it is nevertheless true that his words helped increase racial hatred in the state. Theodore Bilbo, too, is noted for using very racist language, in effect encouraging White people to hate. In Bilbo’s case, however, it should be noted that most of his racially hateful language came in the 1930s and 1940s, after Progressivism had ended.

Looking at Progressivism nationwide, it is clear that even Progressives in the northern states took some bigoted stands that seem wrong as we look back on them. For example, many Progressives believed that persons who had immigrated to our country from Europe were often ignorant, were heavy drinkers, and had a tendency toward crime. Progressives sometimes supported laws to make it harder for immigrants to become citizens, or tried to reduce the number of Jewish and Catholic immigrants coming to this country. Many northern Progressives were unconcerned about the fact that Black Southerners often were not permitted to vote.

Some Progressives got their science wrong and believed that habitual criminals passed their tendency to crime down to their children genetically. Therefore these Progressives supported laws calling for the mandatory sterilization of habitual criminals. These various actions fit the definition of Progressivism because their backers believed that modern science and social science had pointed out these problems, and they were offering new laws to solve the problems.

Thus, not everything that was a part of Progressivism really seems like “progress” in the 21st century. Certainly the views of Vardaman and Bilbo on race don’t seem to invite progress, nor does the action of Mississippi’s legislature in voting against woman suffrage.

On the whole, though, Mississippi did play an important role in Progressivism during the years 1900 to 1917. Many important Progressive laws were passed, and Mississippi tackled many of its problems, including child labor, unsafe factories, inadequate roads, and widespread diseases.

Stephen Cresswell, Ph.D., a native of Jackson, Mississippi, is now a professor of history at West Virginia Wesleyan College. He has written books and articles about Mississippi during Reconstruction and about third-party movements in the state.

Lesson Plan

-

Children work as shrimp pickers at Peerless Oyster Company on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. A Progressive law made it illegal for factories to hire young children under 12 to work in factories. 1911 photograph by Lewis Wickes Hine. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. PI/1986.0031/8/Box 73 R 71/B 1/S 3/ Folder 9 -

Some of the young workers at Laurel Cotton Mills in Laurel, Mississippi. 1911 photograph by Lewis Wickes Hine. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. PI/1986.0031/11/Box 73 R 71/B 1/S 3/ Folder 9

-

Progressives made Prohibition a nationwide policy. Bottles and barrel of confiscated whiskey. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-96026?? -

Progressives set up the State Highway Commission to help bring better roads to Mississippi. The Shell Road in Biloxi, Mississippi, circa 1901. Lighthouse in background. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection, LC-D4-13539 -

One of the young workers at the Kosciusko Cotton Mills in Kosciusko, Mississippi. The lad told the photographer he was 10 and had a regular job at the mill. November 1913 photograph by Lewis Wickes Hine. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-nclc-02882 -

Interior of Magnolia Cotton Mills spinning room in Magnolia, Mississippi. See the children workers scattered throughout the mill. March 1911 photograph by Lewis Wickes Hine. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-nclc-01871

References

Giroux, Vincent A. “The Rise of Theodore Bilbo (1908-1932).” Journal of Mississippi History, XLIII (1981): 180-209.

Holmes, William F. The White Chief: James Kimball Vardaman. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1970.

McLemore, Nannie Pitts. “The Progressive Era,” in Richard Aubrey McLemore, A History of Mississippi. Jackson: University and College Press of Mississippi, 1973 (volume II, pages 29-58).

McMillen, Neil R. Dark Journey: Black Mississippians in the Age of Jim Crow. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989.