Washington, Mississippi, provided the stage in the early 19th century for extraordinary historical events: In 1801 it became the capital of the Mississippi Territory; in 1811, Jefferson College, the only chartered educational institution prior to the statehood of Mississippi opened there; and in 1817, Mississippi’s state constitution was drafted there in a small Methodist Church, which later became part of Jefferson College.

Washington sits near the Mississippi River, six miles northeast of Natchez, and was named in honor of George Washington, the first president of the United States. The town would remain the territorial capital until 1817, the year when the western part of the Mississippi Territory was admitted to the United States as the state of Mississippi, and Natchez was designated the state capital.

Enduring legacy of education

Yet, Washington’s most enduring legacy is its early education history. When the Mississippi Territory was established in 1798, its government was modeled after the 1787 Northwest Ordinance, a law enacted by Congress to establish a government in that territory and to set up procedures by which statehood was to be achieved. The ordinance stated that “schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.”

Thus, Governor of the Mississippi Territory William C. C. Claiborne proposed an institution of learning be established in the territory to drive out “mental darkness” and “become a fruitful nursery of science and virtue.” In 1802, at its first meeting in Washington, the General Assembly approved a bill to construct a school. The assembly appointed a board of trustees and charged them with the responsibilities to find a suitable location for a school, contract for the construction of school buildings, hire instructors, and conduct all business associated with the school. They named the institution Jefferson College in honor of Thomas Jefferson, then president of the United States.

The school’s opening was delayed for nine years due to disputes over its location and inadequate financial support — the General Assembly had not appropriated any funds for it. The eventual choice of Washington for the school’s site fit the town well. By the time Jefferson College opened in 1811, the population in Washington had grown to reflect its status as territorial capital. High officials of the territory made it their home. In addition, Congress had located Fort Dearborn near Washington and situated the important land office west of the Pearl River there.

J.F.H. Claiborne, nephew of Territorial Governor Claiborne, describes Washington as situated in “rich, elevated and picturesque country.” He tells of the many “gentlemen of fortune” who resided there. There were lawyers, doctors, clergy, planters, and politicians. Washington thrived. Streets accommodated large hotels, churches, and businesses and “every hill was occupied by some fine gentleman’s chateaux … parades and public entertainments were the features of the place.” There were wine parties and dinners and “more wit and beauty than we have ever witnessed since.” Its society was “highly cultured and refined.”

Jefferson College opened in this environment with an enrollment of fifteen boys and girls. The goal for the school was to draw students from across the territory, but attendance remained low always and it was difficult to recruit students. While some wealthy parents chose colleges in the North, others sent their sons to Jefferson College.

Jefferson College

Over the years attendance rose and fell at Jefferson College, reaching a top enrollment of approximately 130 students. In 1818, Elizabeth Female Academy opened in Washington, a few miles away from Jefferson College. Within a short period, most of the girls of Washington, and many from Natchez, attended the new girls’ school and Jefferson College became primarily an all-male institution. In 1820 a student could attend Jefferson College for a single session for $16, or $32 for two sessions. Tuition rose to $50 per year in 1825, and to $60 in 1830.

Academic studies at Jefferson College received high priority. The curriculum, which offered some college-level classes, included modern language, mathematics, science, business, and agricultural chemistry. The entrance exam of 1840 included grammar, arithmetic, Latin and Greek grammar and literature, as well as the Bible.

Class schedules were tight. During the summer of 1817, for example, school began at 6 a.m., with breaks for breakfast and lunch, then classes continued until well into late afternoon. Students studied on Saturdays. On Sundays they were expected to attend church. Only the month of August was summer break, and students had two weeks off at Christmas.

Rules were enforced at Jefferson College. In the early years the Journal of the Board of Trustees notes that, “No student shall be seen in a tavern or grog shop or house of ill fame, or at any public place or gathering where gambling, drinking, racing, rioting or any other species of vice prevails. No student shall be absent from school … No student shall laugh or disturb another in school time, nor be idle, nor neglect the task or exercise assigned him … No student shall curse or swear, lie or get drunk or use improper or foolish epithets or indecent or profane language … No student shall be dirty or loose or destroy his clothes nor tear or abuse his books or instruments …” and the list continues.

Many of Mississippi’s early political leaders were associated with Jefferson College. Perhaps the most famous student was the young Jefferson Davis, who in 1861 became president of the Confederate States of America. Territorial Governor Claiborne served as president of the college’s first board of trustees. Albert Gallatin Brown, who later became governor of the state, was a student. Benjamin L.C. Wailes, a noted geologist, was a student and later taught there and served on its board of trustees. Moreover, Wailes contributed greatly to the college museum by donating a sizable number of mineral samples, fossils, and preserved specimens.

The school quickly became an intellectual center for Washington and the surrounding area. The local elite supported the school and participated in several learned societies. Local nurseryman Thomas Affleck hosted agricultural fairs and published proceedings in national journals. He organized the Agricultural, Horticultural, and Botanical Society of Jefferson College. The Washington Lyceum, formed around 1837 and based at Jefferson College, organized standing committees on belles-lettres and mental science, moral philosophy and theology, constitutional law and political economy, natural history, mathematics and physical science, antiquities and history, and anatomy and physiology. The Lyceum published an important literary journal, and undertook investigations of local Indian mounds.

Evolution to historic public property

With the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 enrollment at Jefferson College dropped dramatically and the school came upon hard times. It closed in 1863. After the war, Jefferson College had become a Freedmen’s Bureau school by June 1865 to educate recently freed enslaved people. In November of that year, the school was returned to the Jefferson College Board of Trustees at the request of the trustees.

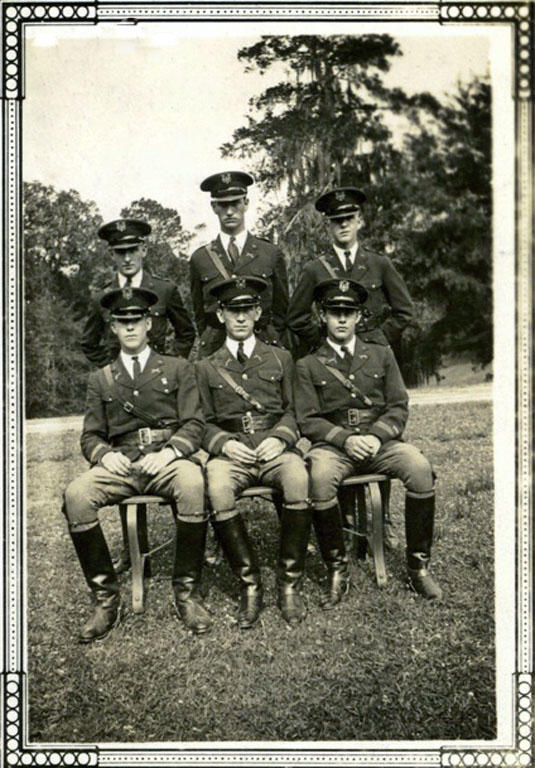

Jefferson College reopened in 1866 as a preparatory school. Although it kept the name college it never again offered college-level classes. By the early 20th century the school had evolved into a military preparatory school known as Jefferson Military College. It functioned as a military school until steep debts and lack of enrollment forced it to close forever in 1964, as did other Southern military schools.

The Mississippi Building Commission purchased the site in 1964, and in 1971 transferred the title to the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. By this time, the buildings were in shambles and the grounds were overgrown. Buildings and grounds were restored and today, known as Historic Jefferson College, it is a beautiful, historic site with eight remaining school buildings dating from 1817 to 1937.

When approaching the school, one notices two very large, three-and-a-half-story brick buildings known as the East Wing and West Wing. Completed in 1819, the East Wing was the first portion of the college constructed by builder Lewis Evans and architect Levi Weeks. The East Wing provided residential, classroom, and meeting spaces as well as a state-of-the-art science laboratory and a museum “filled with curiosities from every part of the earth.” The matching West Wing was completed in 1839. The circa 1835 President’s House, which was purchased for the school in 1842, is now a private residence on the campus. A gymnasium, constructed in 1894, was demolished during the site renovation. Three 20th century dormitories remain on the campus, including Raymond Hall (1915), Prospere Hall (1931), and Carpenter Hall (1937).

Cheryl Munyer Waldrep, a former branch director for Historic Jefferson College, holds a bachelor’s degree in history and a master’s degree in historical administration from Eastern Illinois University.

Lesson Plan

-

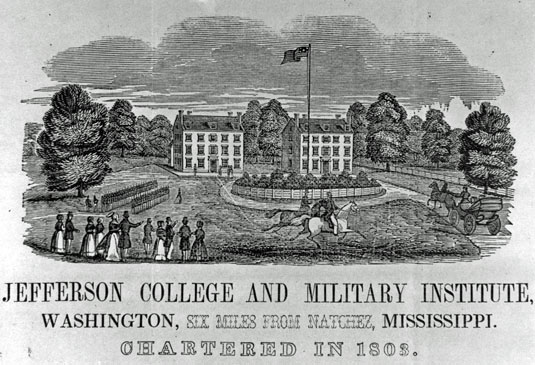

Early woodcut of Jefferson College, Washington, Mississippi. Image courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI ED J43 11. -

West and East wings of Jefferson College in 1970, before restoration. The East Wing was constructed in 1819 and the West Wing in 1839. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

-

Restored West Wing at Jefferson College. Courtesy of photographer Cheryl Munyer Waldrep. -

Kitchen at Jefferson College, photographed April 15, 1936, by James Butters. The kitchen building was constructed in 1839. Courtesy Historic American Building Survey, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, No. HABS MISS,1-WASH, 2-B-1. -

Renovated kitchen at Jefferson College, photographed in 2005. Courtesy of photographer Cheryl Munyer Waldrep. -

Cadets at Jefferson Military College. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI ED J43 58. -

Raymond Hall at Jefferson College, constructed in 1915. June 1970 photograph Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI ED J43 11. -

The circa 1835 President's House, which was purchased for the school in 1842, is now a private residence on the campus. Photographed January 2008 on a rare snowy day for south Mississippi. Courtesy of photographer Cheryl Munyer Waldrep.

References:

Blain, William T. Education in the Old Southwest: A History of Jefferson College. Natchez, Mississippi: Friends of Jefferson College, 1976.

Bunn, Michael and Clay Williams. Mississippi’s Territorial Years: A Momentous and Contentious Affair, Mississippi History Now (November 2008).

Branyan, Cheryl and H. C. Burkett. “Historic Jefferson College.” Mississippi Gardener, (March 2005): 44-45.

Branyan, Cheryl Munyer. “Jefferson College in Washington, MS.” Antiques Gazette, vol. 21, no. 12 (July 2005): 13-14.

Burkett, H. Clark. “Jefferson College, The Freedmen’s Bureau, and Union Occupation.” Journal of Mississippi History, Vol LXVI, No. 2 (Summer 2004).

Claiborne, J. F.H. Mississippi as a Province, Territory, and State with Biographical Notices of Eminent Citizens. Spartanburg, South Carolina: The Reprint Company, 1976.

Haynes, Robert V. “The Formation of the Territory,” A History of Mississippi, Volume One, edited by Richard Aubrey McLemore. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1973.

Mississippi Department of Archives and History Historic Jefferson College

Rowland, Dunbar, ed. Mississippi Volume I: Comprising Sketches of Counties, Towns, Events, Institutions, and Persons, Arranged in Cyclopedic Form. Spartanburg, South Carolina: The Reprint Company, 1976.