The study of historic architectural styles provides us a unique way to learn how our ancestors lived and worked, how and what they built, and what they thought about themselves and their society as expressed in their buildings. Mississippi has a wide variety of architectural styles. Here is an overview of them.

Vernacular style

Vernacular architecture is a traditional form of building that reflects local environmental influences, uses locally available building materials, and is passed down from generation to generation. The earthen mounds built by prehistoric native peoples are Mississippi’s oldest examples of vernacular architecture, if architecture is defined simply as structures built by humans. The mounds were elevated bases for either temples or homes of tribal leaders, or they may have served as elevated ceremonial platforms. Winterville Mounds near Greenville and Emerald Mound near Natchez are two of the best examples of prehistoric structures in Mississippi.

European colonists built the oldest surviving buildings in the area that would become the state of Mississippi. Timber was plentiful and early buildings in Mississippi were constructed with heavy timber framing. Brick was used to a lesser extent; very little stone was used since it was difficult and expensive to acquire.

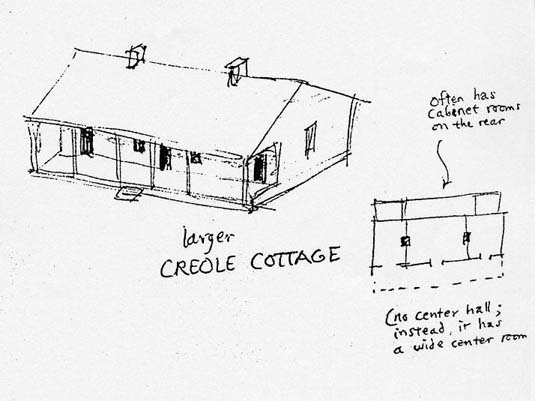

The French were the first Europeans to establish permanent settlements on the Gulf of Mexico coastline in 1699 near present-day Ocean Springs, Mississippi, and around 1716 along the Mississippi River at present-day Natchez. The early colonists developed a house form based on their French building traditions, use of local building materials, and construction that made it easier to endure the effects of the hot and humid climate. Their house form is called the Creole Cottage. It is a one-story, or one-and-one-half-story, house that is one-room deep, two or three rooms wide, with an overhanging roof sheltering an undercut front gallery, or porch. It is usually built on a raised foundation. The back of the cottage might have a rear gallery, but often there is a recessed loggia, a centered small porch open to the outside on only one elevation. The loggia is flanked by smaller rooms, called cabinet (pronounced kah-be-nay) rooms. Access to the second, or attic, floor is usually by a ladder or small staircase from the rear loggia or a cabinet room.

A good example of a Creole Cottage, and the earliest surviving building in the lower Mississippi River Valley, is the De La Point-Krebs house in Pascagoula, Mississippi. It was built around 1770 as part of an early plantation.

After 1763, the British were the next Europeans to take control of this area and it became British West Florida. Many settlers of British ancestry moved into the area from the country’s older east coast colonies, or from Britain itself. Since the Creole Cottage form developed by the French worked very well in the hot humid climate, many elements of the form were retained. The Anglo-American settlers, however, did bring some ideas of their own. While the Creole Cottage is horizontal in orientation, a long, thin form that appears to hug the ground, the new colonists brought forms that were more vertical. King’s Tavern, believed to be the oldest standing structure in Natchez, is a good example of this influence. King’s Tavern is a full two stories and has an attached porch rather than the integral undercut gallery.

The British lost control of West Florida to the Spanish during the American Revolution. In 1790 the Spanish laid out the new town of Natchez on the Mississippi River bluffs. Prior to this, Natchez consisted only of the settlement along the banks of the river with Fort Rosalie on the bluffs above. The best example of Spanish Colonial architecture in Natchez is Texada, a town house built in the late 1790s by Manuel Texada. As originally constructed, this two-and-one-half-story brick house had living quarters on the second floor. The first floor was built for commercial use. The town house sits directly adjacent to the sidewalk; the porch is on the rear. Texada is the oldest surviving brick building in Mississippi.

The Spanish left in 1798 when the United States took control of the area and established the Mississippi Territory. Many settlers from the older, established areas of the United States flowed into the new territory and brought with them their own vernacular architectural traditions.

While the new settlers adopted the Creole Cottage, they too made changes to reflect their traditions, particularly the addition of the center hall, one of the characteristic architectural elements used by the Anglo-American settlers. In a house built along typical Anglo-American lines, the front entrance opens into a wide center hall flanked by one or two rooms. If there is an upper floor, the staircase usually rises from the center hall.

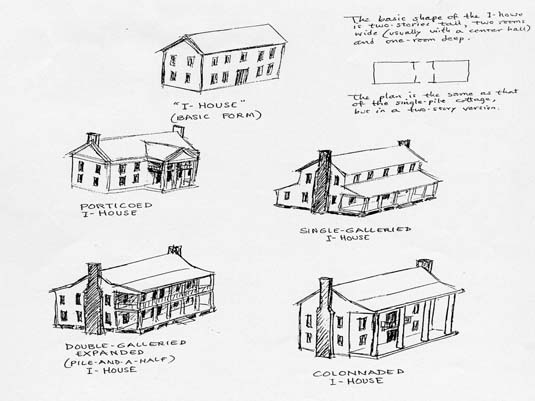

The settlers also brought the log cabin to Mississippi. Introduced to North America by Scandinavian colonists in the 17th century, log construction quickly became popular among all North American colonists since the log cabin made sense in a country with abundant forests. Consequently, many Mississippians lived in simple one-room log cabins. Often the early cabins were expanded by the addition of a second cabin connected to the first by an open passage known as a “dog trot.” A dog trot is different from a center hall although the two are often confused. A center hall was built as an enclosed room with doors at each end. A dog trot is an open passageway with no provision made to close off the ends. Many dog trots were later enclosed however. A more formal house type introduced by the new settlers is the I-House; a two-story, one-room deep house, usually with a center hall.

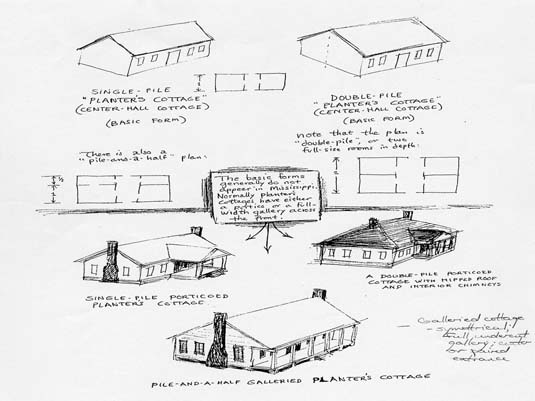

Another vernacular house form built in Mississippi during the 19th century was the Planter’s Cottage. The Planter’s Cottage is a small, one-, or one-and-one-half, story house with a center hall and usually either one or two rooms deep. It can be further defined by whether it has a portico or a gallery across the front. Generally the porticoed version is found in North Mississippi and the galleried version in South Mississippi. The use of the term “Planter’s Cottage” does not indicate that all the houses were built for or occupied by planters. In fact, many were built in towns and cities for doctors, lawyers, merchants, and other professionals. The term reflects that this relatively small and modest house form was the most common type found on many Mississippi plantations. The large two-story, columned mansion, which is often associated with the plantation, is more often found in or near a settlement and are town houses, or suburban villas, rather than plantation houses.

These basic vernacular forms dominated Mississippi’s early domestic architecture until after the American Civil War. Other buildings constructed during this earliest period, such as courthouses, schools, stores, banks, and churches, were generally one-room structures devoid of any individual architectural character.

Federal style

The first architectural style to appear in Mississippi was the Federal style. This style, based on the neo-classical architecture of the British architects Robert and James Adam, was the most popular architectural style along the eastern coast of North America during the early years of the Federal Republic, hence the name Federal style. It makes use of classical columns and ornament inspired by ancient Roman architecture. In addition to the classical columns, the Federal style is identified by the use of semi-circular fanlights over doors, oval windows in pediments, and delicately carved interior woodwork. The best Federal style architecture in Mississippi is found in the old Natchez District, the area of Southwest Mississippi centered on Natchez, since it was the wealthiest, most settled area of the state at the time. The best example of this style is Auburn, a suburban villa constructed near Natchez about 1812.

It was also during the Federal style period that the first substantial public buildings, churches, and commercial buildings began to appear. The First Presbyterian Church in Natchez and the Presbyterian Church at Rodney are good examples of this style.

Greek Revival style

In the 1830s, the Greek Revival architectural style first appeared in Natchez and is the style most often associated with the antebellum South. The Greek Revival style, identified by its tall white columns, is a reinterpretation of the architecture of Ancient Greece, the birthplace of democracy. The idea of reviving the architecture of ancient democracy in the world’s first modern democracy appealed to early 19th century Americans and became the first style found throughout the country. Greek Revival dominated building in Mississippi until after the Civil War. Ancient Greek temples were built of stone, but Americans usually built their new “temples” of wood or brick, covered in stucco and decorated to look like stone. The Greek Revival style was used for residences, banks, schools, courthouses, churches, commercial buildings, state capitols, hospitals, and even outhouses. There are many theories as to why this style remained popular for so long. One of the obvious is that a monumental building could be created with readily available local materials and with relatively modest craftsmanship.

The first Greek Revival structure in Mississippi is the Natchez Agricultural Bank of 1833. It was quickly followed by the houses Ravenna and Richmond, both circa 1835. The Commercial Bank of 1836, also in Natchez, is the only Greek Revival structure in Mississippi with a real marble façade. Perhaps the most famous Greek Revival buildings in Mississippi are the Old Capitol, circa 1840, and the Governor’s Mansion, circa 1842.

Gothic Revival style

The first non-classical architectural style to become popular in Mississippi was Gothic Revival. This style imitated the great stone cathedrals and castles of Europe but was adapted to American needs and materials. The ready availability of lumber and factory-made architectural trim created a distinctly American version of Gothic Revival. Hallmarks of the style are steeply pitched roofs that give a sense of height and a strong vertical emphasis, elaborate gable decorations, pointed arch windows, board and batten siding, stucco over brick treated to imitate stone, and one-story porches. The Gothic Revival style was used primarily in Mississippi for churches such as the Chapel of the Cross in Madison, Grace Episcopal Church in Canton, St. Mary’s in Natchez, and the Church of the Annunciation in Columbus. There were several fine houses built in the style as well, such as the Manship House in Jackson and Airliewood in Holly Springs.

Romanesque Revival style

A related style is the Romanesque Revival style. Before the Civil War it was used exclusively on churches as an alternative to the Gothic Revival. The main difference was the use of round or Roman arches instead of the pointed arches of the Gothic. The best known example of this style in Mississippi is the First Presbyterian Church in Port Gibson.

The Romanesque style returned after the war, and while still employed as religious architecture, it found its way into many other building types. No known houses were constructed in this style, however. The style remained popular in Mississippi until the early 1900s. Buildings in this style are usually constructed of brick with low, broad Roman arches, often incorporating patterned masonry over windows and doorways. Some good examples of buildings in the Romanesque style include the Tate County Courthouse at Senatobia, the old Wesson School at Wesson, and Trinity Episcopal Church in Vicksburg.

Italianate style

The Italianate style was the next architectural style to arrive in Mississippi. Beginning in England with the picturesque movement of the 1840s when builders began to design fanciful recreations of Italian Renaissance villas, Italianate was the most popular house style in the United States by the late 1860s, and remained so in Mississippi until the 1880s. Italianate houses generally have low pitched roofs, wide overhanging eaves with heavy brackets and cornices, and Roman or segmented arches above the doors and windows. Italianate houses also tend to be more irregular and asymmetrical in plan than earlier styles and often incorporate towers or cupolas. Italianate was also readily adapted to other building types and was especially popular for commercial buildings. Among the best of Mississippi’s antebellum Italianate houses are Ammadale in Oxford and Rosedale in Columbus. Vicksburg has many fine postbellum Italianate houses, such as the Beck House.

Eclectic style

By the mid-1850s, many Mississippians began to meld the Greek Revival style with the Gothic Revival and Italianate to produce a very eclectic style. While this occurred all across the state, nowhere was it as successful as in Columbus. Some of the best examples of this type are the Old Fort House and Shadowlawn.

After the Civil War ended and Mississippians began to put their lives back together and to repair war-damaged buildings or to build anew, they built at first in one of the many styles popular before the war. It wasn’t long, however, before a new way of building and a new style emerged.

Victorian Vernacular style

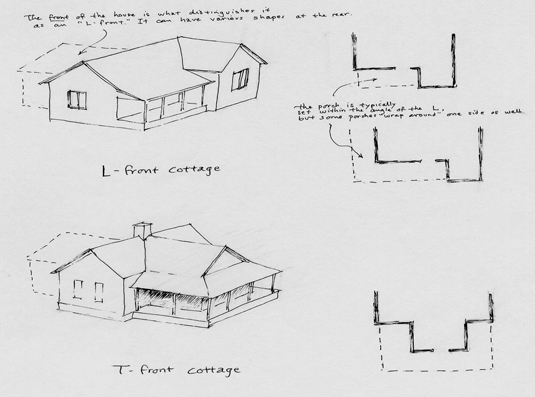

As the railroads across the state were repaired and expanded following the war, factory-made building parts could be sent to far corners of the state from virtually anywhere in the country. The rise of industrialization after the war made it easier and more affordable to add decorative details to otherwise simple buildings. A crate of mass-produced decorative trim, such as scrolled brackets, might find its way from Chicago or St. Louis to carpenters in Brookhaven or Iuka where they could mix and match the pieces according to personal whim, or whatever they had on hand. Moreover, sophisticated woodworking machinery was now available. Many buildings and houses were adorned with flat, jigsaw-cut trim in a variety of patterns or they were decorated with spindles or other lathe-turned woodwork. For ease of classification this style is referred to as the “Victorian Vernacular” style. Buildings are usually square or rectangular and symmetrical in shape, often with projecting front wings that give the floor plan the L shape.

Second Empire style

The Second Empire style, a style similar to the Italianate style, made a brief appearance in Mississippi immediately after the Civil War. While this style was developed in France during the reign of Napleon III in the 1850s and based on the elaborate architecture of 17th century France, it did not reach Mississippi until after the war was over. Once the war ended and new construction began, very few people had the money or interest to build in such an elaborate style. The main feature of this style is the tall mansard roof, and the best example of the Second Empire style in Mississippi is the Schwartz House in Natchez.

Queen Anne style

The first new formal architectural style to arrive in Mississippi after the Civil War was the Queen Anne style. The style originated in Great Britain in the 1870s as a protest over the industrialization of architecture. To find an architectural style that they viewed to be more correctly British, many British architects looked back to styles of the late 17th and early 18th centuries — the era of Queen Anne, hence the name. Ironically, when Queen Anne style became popular in the United States in the 1880s and 1890s, the new technologies of the industrial revolution encouraged builders to use mass-produced pre-cut architectural trim to create fanciful and sometimes flamboyant buildings. As a result, the style was “corrupted” to become what its originators had protested against.

The Queen Anne style arrived in Mississippi in the 1880s and remained popular through the early years of the 20th century. In fact, when people use the term “Victorian house” they are usually referring to the Queen Anne style. Queen Anne houses and buildings often have towers, turrets, wrap-around porches, and other fanciful details inspired by the late Gothic and early Renaissance architecture of Great Britain. Among Mississippi’s best houses in the Queen Anne style are the McCloud House in Hattiesburg, the Jones-Biggers House in Corinth, and the Keyhole House in Natchez. The Queen Anne style was used effectively on public and institutional buildings such as the River Commission Building in Vicksburg, Ventress Hall at the University of Mississippi, and the Holmes County Courthouse in Lexington.

Todd Sanders is an architectural historian at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

*This is the first part of a two-part article on Mississippi architecture. The second part is Architecture in Mississippi During the 20th Century.

Lesson Plan

-

The French colonists developed the Creole Cottage, the earliest house form designed in the area that would become the state of Mississippi. Drawing by Richard Cawthon. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

The De La Point-Krebs house in Pascagoula, Mississippi, built around 1770, is a good example of the Creole Cottage, and is the earliest surviving building in the lower Mississippi River Valley. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

-

Anglo-American settlers introduced the vernacular I-House form to Mississippi. Drawing by Richard Cawthon. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Drawings of the vernacular Planter's Cottage, the most common house form found on many Mississippi plantations. Drawing by Richard Cawthon. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Auburn, a suburban villa built near Natchez about 1812, is an example of the Federal style. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Ravenna, a Greek Revival house in Natchez, was built in 1835. The Greek Revival architectural style is the one most often associated with the antebellum South. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

The Commercial Bank in Natchez, built in 1836, in the only Greek Revival structure in Mississippi with a real marble facade. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Grace Episcopal Church in Canton, Mississippi, is an example of Gothic Revival, a style that was used primarily in Mississippi for churches. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Airliewood in Holly Springs, Mississippi, is a fine example of a Gothic Revival house. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

The Tate County Courthouse in Senatobia, Mississippi, is built in the Romanesque style. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Rosedale in Columbus, Mississippi, is an antebellum Italianate style house. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Many Mississippians combined the Greek Revival style with Gothic Revival and Italianate to produce an eclectic style. Shadowlawn in Columbus, Mississippi, is eclectic style. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Houses built in the Victorian Vernacular style often had the L-shape floor plan. Drawing by Richard Cawthon. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

The Schwartz House in Natchez is Second Empire style. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

The Keyhole House in Natchez is among the many houses in the Queen Anne style. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Reference:

Statewide Inventory Files (Historic Preservation Division), Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Suggested reading:

Crocker, Mary Wallace. Historic Architecture of Mississippi. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi, 1973.

Delehanty, Randolph, Van Jones Martin, Ronald W. Miller, Mary Warren Miller, and Elizabeth Macneil Boggess. Classic Natchez. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1996.

Miller, Mary Carol. Great Houses of Mississippi. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi, 2009.

Miller, Mary Carol. Lost Mansions of Mississippi. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi, 1996.

Sanders, Todd. Jackson’s North State Street. Mount Pleasant, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2009.