Mississippi had pockets of strong local civil rights activity before the Freedom Riders entered the state, but their presence in 1961 propelled the local movement to new heights.

Most of the local civil rights movements began in the 1950s, in churches, homes, and in the back rooms of small black-owned businesses across the state. Their activities were quietly organized, and struggles against discrimination were small and localized, because it was too dangerous to make large public statements and draw too much attention to the activists. The whites in power who wanted to maintain and strengthen segregation had little tolerance for black resistance, and they worked hard to navigate ways out of implementing the 1954 U. S. Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education decision that ruled segregated public schools unconstitutional. But their efforts did not kill the local civil rights movements.

Clarksdale and the NAACP

Before the young people in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee or the Congress of Racial Equality entered Mississippi on the Freedom Ride buses in 1961, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People had branches throughout Mississippi. Most of the state’s NAACP branches were formed after World War II had ended in 1945. Moreover, in the early 1950s the national office in New York City sought to increase its membership and build on the momentum from its Supreme Court successes in dismantling Jim Crow, or the system of denying African Americans civil liberties and enforcing segregation. Some Mississippi branches were more organized and viable than others, depending on the areas where active and strong all-white Citizens’ Councils or more violent vigilante groups had also organized.

One of the most active NAACP branches was in Clarksdale, Mississippi, covering the whole of Coahoma County. In 1951 a group of local black people, under the leadership of World War II veteran and pharmacist Aaron Henry, formed a Clarksdale/Coahoma County NAACP branch to harness the resources of the larger national organization. The group received its charter in 1953 and remained at the fore of civil rights activities in the Mississippi Delta for years. In fact, the branch had such a large active membership that SNCC and CORE had little to do there and focused more on other towns and counties in the state.

Vera Mae Pigee, who owned a beauty shop in the heart of the black neighborhood in downtown Clarksdale, had helped Henry organize the Clarksdale/Coahoma County NAACP chapter. She then worked principally with local black youth under the auspices of the NAACP Youth Council program. Pigee also served as Clarksdale/Coahoma NAACP branch secretary and as the state’s Youth Council advisor. The Youth Council undertook many activities that helped the adult officers and leaders of the local branch meet their goals. For instance, in the spring of 1961 many young people went door-to-door in Clarksdale during the NAACP’s Crusade for Voters. They also announced the program in their churches and schools. The result of the Youth Council efforts produced one hundred new voters.

Pigee and Youth Council

The 1961 Freedom Riders did not pass through Clarksdale, yet the town’s civil rights activities in 1961 were strong, producing local drama and stories. For example, on August 23, a Wednesday afternoon after lunch, three black youths walked into the white waiting room of the Illinois Central Railroad Station in Clarksdale. They approached the ticket agent and asked for tickets for the next Memphis-bound train. The agent refused them service and a bystander called the police and the local newspaper. The young people were Mary Jane Pigee, aged eighteen, a college student at Central State College in Wilberforce, Ohio, and a former local Youth Council president; Adrian Beard, aged sixteen and a student at Immaculate Conception Catholic School; and fourteen-year-old Wilma Jones, a student at Higgins High School. When Police Chief Ben C. Collins arrived with another officer, the protesters refused to move to the “colored side” of the station and remained quietly seated. The officers took them into custody and charged them with intent to breach the peace.

The Youth Council, under the leadership of Vera Pigee, the mother of Mary Jane, had sponsored the demonstration, and it resulted in their first formal direct-action arrest. The Youth Council wanted to test the breach of peace statute that so many young people had “violated” in the last twenty months since the beginning of the mass sit-ins across the nation and the Freedom Rides in action elsewhere. The local jury convicted the three young people on the basis they had violated a Mississippi statute that segregated waiting rooms.

Pigee encouraged her daughter’s desire to participate in protests and sit-ins despite the obvious risks. To be a mother — to her daughter and to the Civil Rights Movement — was for Pigee a duty and a great responsibility. Her confidence convinced others that she did not ask of them what she was not willing to do herself. She could assure parents of their children’s safety while in her care and gained their trust through her own struggles. She did not let the youth take the burden of direct action alone.

In fact, in the fall of 1961, weeks after her daughter’s own protest at the railway station, Pigee and Idessa Johnson, another member of the NAACP Clarksdale branch, walked into the whites-only section of the Clarksdale Greyhound Bus Terminal. It was a personal goal for Pigee to desegregate the bus terminal. Pigee knew that her daughter would not use the designated black side of the terminal when she traveled home from college at Christmas. Pigee decided to protest on Mary Jane’s behalf. On entering the terminal, the women did not find resistance, and Pigee asked for a round-trip ticket from Cincinnati, Ohio, to Clarksdale and for an express bus schedule. The transaction took place without incident. Pigee and Johnson walked away slowly, pausing to marvel at the spacious, air-conditioned white section, drinking at the water fountain, and visiting the ladies room before leaving.

Mary Jane Pigee came home for Christmas entering on the white side of the bus terminal. But when it was time for her to return to school, four policemen entered the white waiting room where she sat with her mother and a family friend. Harassing them with a barrage of questions, the officers threatened arrest. The women filed complaints with the NAACP, U. S. Department of Justice, Interstate Commerce Commission, local F.B.I., and police. Protesters repeated the ritual until on December 27, 1961, the Clarksdale Press Register reported that all the segregation signs had disappeared from the Clarksdale bus terminal and the Clarksdale train station. Police had voluntarily removed the signs after the Justice Department informed the city that it faced a law suit.

Pigee’s desegregation of the bus terminal symbolized the beginning of a more aggressive style of protest in Clarksdale, one already practiced in other counties and southern states. Their actions in Clarksdale took shape against the backdrop of rising student-led protest across the South, a mass of movements that increasingly pushed well past the adult leadership of old-line civil rights organizations, such as their beloved NAACP.

Women and the Movement

On Thanksgiving Day in 1961, for instance, Clarksdale’s mayor banned the two bands from black Higgins High School and Coahoma County Junior College from the annual Christmas Parade, a tradition for the black schools since the late 1940s. Rather than discouraging civil rights activities, the mayor’s move added fuel to the protest fires. Working with the children in the Youth Council, Pigee had immediate contact with the black parents. Punishing the youth during the season of good will provoked angry parents to act when they might not have before. Indeed, it was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. The Youth Council debated its response at Pigee’s beauty shop in a mass meeting, which Pigee had called the night following the ban announcement. Pigee said, “These are our children,” and it was that sentiment that sustained a two-year boycott of downtown businesses under the phrase, “No Parade, No Trade.”

Vera Pigee (1925-2007) was an exceptional woman who helped build and run the Clarksdale Civil Rights Movement through her work with the NAACP branch and the Youth Council in the 1950s and 1960s. There were women like her in every community in the South, women who extended the work they did as mothers, wives, and caregivers to include local organizing for communal well-being. It helped that Pigee had a supportive husband and was independently employed, owning and running a beauty salon where she organized for the Civil Rights Movement, ran citizenship classes to teach literacy skills, and made a living. In her salon she talked about the movement with her clients, went through the voting registration papers with them, and organized events while she worked on their hair. The salon shielded her civil rights work from view because most people would not suspect that vital meetings took place there, and most men (black or white) did not enter female-centered spaces. Pigee’s beauty shop was a safe space for the community, particularly the women and the Youth Council, to have conversations and develop strategies. In that space, many learned about politics and the power of their own voices. In many ways, therefore, Pigee could do a lot of her civil rights work under the radar, out of the spotlight.

Yet it is because of this kind of work that history has forgotten to include her and other women into the civil rights stories. Since she did not deliver large televised speeches or get her picture taken for publication in national papers with important people, she is little known, as are the other local women activists. Therefore, while 1961 is a crucial date in the larger civil rights narrative that brought the Freedom Rides to Mississippi and SNCC and CORE into direct action, the local people who carried out important and successful organizing efforts where the cameras did not find them should also be acknowledged. It was the local NAACP branch which ran the active and vibrant Clarksdale Civil Rights Movement and women like Vera Mae Pigee who helped unfailingly in the struggle.

Françoise N. Hamlin is professor of Africana Studies and history at Brown University.

Lesson Plan

-

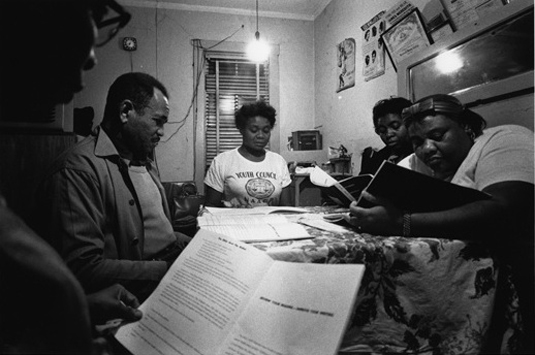

Vera Mae Pigee with a customer in her Clarksdale beauty shop. Charles Moore photograph copyright Charles Moore Estate/BlackStar Inc. -

Vera Pigee, center, teaches literacy skills to Clarksdale residents in her citizenship classes. Charles Moore photograph copyright Charles Moore Estate/BlackStar Inc.

-

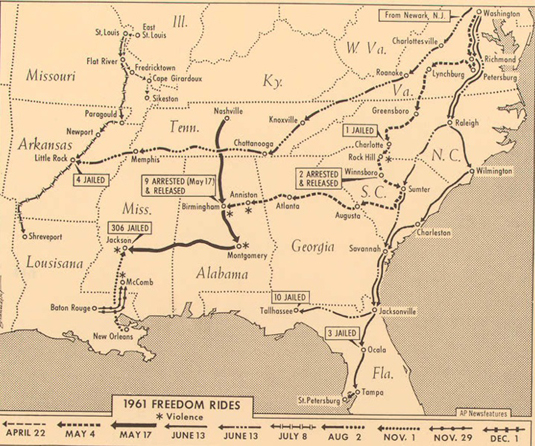

Routes taken by the 1961 Freedom Rides, which aimed to integrate bus, rail, and airport terminals across the South. Courtesy the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, 0904003r. -

Vera Pigee, second from right, with other civil rights workers. Left to right: J. D. Rayford Jr., unidentified woman, C. T. Vivian, Noelle Henry, Pigee, and Rev. Frazer Thomason. Photograph from the Margaret J. Hazelton Collection, McCain Library and Archives, The University of Southern Mississippi. -

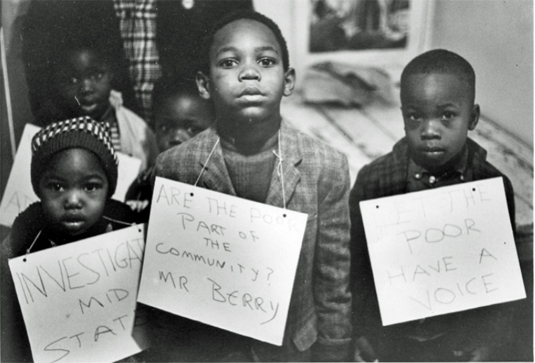

The Youth Council undertook many activities throughout the 1960s that helped the adult leaders of the local NAACP branch meet their goals. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, T_013_3.

Hamlin, Françoise N. “The Book Hasn’t Closed, The Story Isn’t Finished: Continuing Histories of the Civil Rights Movement.” PhD diss., Yale University, 2004.

Hamlin, Françoise N. “Vera Mae Pigee (1925- ): Mothering the Movement.” Proteus: A Journal of Ideas 22:1, Spring 2005, 19-27.