In the aftermath of the Civil War, White Southerners rewrote history in an attempt to vindicate their violent rebellion against the United States. They developed and promoted an ideology known as the Lost Cause. Historian Ty Seidule defined “the Lost Cause myths: the Civil War was about state’s rights, not slavery; enslaved people were loyal; slavery would have ended soon after the war anyway; the North won because of greater resources; and Robert E. Lee was a great warrior who opposed slavery.” None of these myths are true, but they successfully infiltrated American culture and were accepted as fact into the twenty-first century.

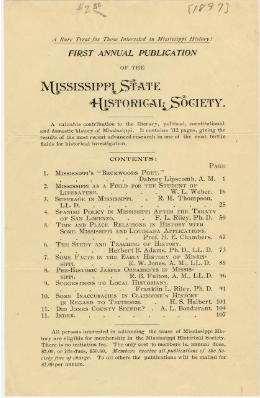

Lost Cause historical writings reinforced the myths of the Lost Cause and tried to justify slavery, secession, the Civil War, and efforts to resist Reconstruction. Many of these writings are contained in the fourteen volume series Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society (1898-1914) with contributions from historians, memoirists, and essayists. Mississippi’s Lost Cause writers went to great lengths to describe slavery as a benign paternal institution where masters cared for their slaves as they did their family. Writers often lauded antebellum slavery as the gentlest form of servitude in history. In describing the cause of the Civil War, Lost Cause writers focused on political disputes over states’ rights, ignoring the fact that the rights in question concerned slavery. They praised the valiant efforts of supposedly superior Confederate officers and soldiers and blamed their military defeat on a lack of adequate resources. Promoters of the Lost Cause criticized Reconstruction—a time when freedmen gained the vote and became politically active—as a period of darkness and turmoil within the state. Furthermore, they characterized the Ku Klux Klan as a noble institution trying to restore the South’s former glory and protect White virtue. Lost Cause authors played down or ignored the horrors of slavery, minimized the fight to preserve the institution, and supported efforts during Reconstruction to oppress the Black population through intimidation, violence, and lynching.

Confederate president Jefferson Davis was the leading proponent of the Lost Cause with his two-volume work The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government in 1881. He falsely claimed that the Civil War resulted from a dispute over states’ rights, not slavery. Davis ignored the role of slavery as the prevailing issue. In fact, he described slavery as “the mildest and most humane of all institutions to which the name ‘slavery’ has ever been applied.” In his telling, slavery “was far from being the cause of the conflict.” The truth is found in Mississippi’s Ordinance of Secession from January 1861, in which delegates declared, “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world.” Two months later, Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens of Georgia agreed in a famous speech in which he identified slavery as “the immediate cause” of the war.

Lost Cause advocates wanted their perspective of Southern history—the one that ignored both the central role of slavery and President Abraham Lincoln’s “proposition that all men are created equal”—to prevail among future generations. In an address at Franklin Female College in Holly Springs, Judge Jeremiah Watkins Clapp, a former plantation owner and Mississippi state senator, urged the students “to see to it that our children shall not, at school or at home, shape their ideas or acquire their information and impressions from books or other sources of character calculated to poison their minds and their hearts and teach them lessons of humiliation and shame.” He continued, “There is much danger, unless these books are made to represent facts as they appear from a Southern standpoint.” He further advised that Mississippi’s White children should be taught “to think and feel that they are descended from an illustrious line of ancestry, and that the noblest blood that has ever coursed through Americans veins has been that that was warmed by Southern suns.”

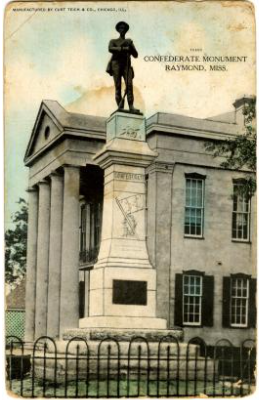

In addition to historical writing, Southern White leaders propagated Lost Cause themes through monument building and memorializing Confederate heroes. In 1866, Governor Benjamin Humphreys encouraged historical societies in the state “to preserve the memorials of the recent sanguinary struggle [and preserve] durable records in the form of maps, charts and diagrams of the movements and counter movements of both armies, together with the heroic part acted by our brave people, [so it] will be transmitted to posterity, to whom we appeal for the vindication of the truth of history and the rectitude of our cause.” The Mississippi Division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, organized on April 1, 1897, led many of the efforts to erect dozens of monuments throughout the state. In addition, they influenced the teaching of history in schools to preserve the vision of the Lost Cause.

Most of the state’s monuments emerged during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when White Mississippians established Jim Crow laws that severely restricted the rights of the Black citizenry. Jim Crow laws in Mississippi codified segregation, adopted a poll tax for voting, and unequally distributed education funds to White schools. The monuments stood as a symbol of this White supremacist order that had overturned Reconstruction efforts to grant equality under the law and Black male suffrage.

As the twentieth century progressed, more dangerous Lost Cause tenets started to emerge at the expense of Black Americans. Popular films such as The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Gone with the Wind (1939) brought Lost Cause tropes into the mainstream. They portrayed slaves as content in slavery on idyllic plantations, but also as brutish as freedmen following emancipation. The Birth of a Nation glorified the Ku Klux Klan as defenders of Southern tradition and culture in the wake of the Civil War and Black men as degenerate marauders intent on defiling Southern women. The film’s popularity led to a resurgence of the Klan in the 1920s when its membership nationwide swelled to upwards of five million. While the Klan was not as strong in Mississippi during its second iteration, a number of White people sympathized with the organization and their racial attitudes.

The Lost Cause myths contributed to many Americans being misinformed about the Civil War and its legacy. These distortions supported the belief that White people are a superior race. These beliefs infected the entire nation, North and South, causing lasting damage by reinforcing racism. The cause of the Confederacy was not noble because it supported slavery. Any honest reckoning with American history requires repudiation of the Lost Cause myths.

Generations of American students were taught a Lost Cause mythology that masked the hard truth about the Civil War – that it was fought to preserve slavery. This Lost Cause ideology was designed to glorify the Confederate cause and to reinforce White supremacy. An honest reckoning with American history requires that students dismiss the Lost Cause mythology and understand the brutality of the slave system and its enduring legacy.

Mike Goleman is the Department Chair of Humanities, Fine Arts, Social Sciences at Somerset Community College in Somerset, Kentucky. He earned a master's and Ph.D. in history at Mississippi State University.

Lesson Plan

-

Civil War Centennial Parade, Jackson, Mississippi, March 28, 1961. The parade was over six miles long and boasted more than 3,000 men dressed as Confederate soldiers. Image courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Confederate monument unveiled April 28, 1908, in Raymond, Mississippi. The Nathan Bedford Forrest Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy sponsored the monument. Image courtesy of the Cooper Postcard Collection at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

-

The Lost Cause was perpetuated in some of the early publications of the Mississippi Historical Society. Image courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Civil War Centennial Parade, Jackson, Mississippi, March 28, 1961. View of Daughters of Confederacy. Image courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Karen Cox, Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. University Press of Florida, 2003.

Edward R. Crowther, ed. The Enduring Lost Cause: Afterlives of a Redeemer Nation. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2020.

Jefferson Davis, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, 2 vols. New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1881; 1958.

Gaines M. Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Michael J. Goleman, Your Heritage Will Still Remain: Racial Identity and Mississippi’s Lost Cause. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2017.

Sally Leigh McWhite, “Echoes of the Lost Cause: Civil War Reverberations in Mississippi from 1865 to 2001.” Ph.D. diss., University of Mississippi, 2003.

Franklin L. Riley, ed., Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society, 14 vols. University, MS: Printed for the Society, 1898-1914.

Ty Seidule, Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2020