In 2022, more than fifty African Americans were serving in the Mississippi State Legislature, carrying on the legacy of the first Black men who served there in 1870. Mississippi’s first Black legislators were farmers and lawyers, barbers and blacksmiths, teachers and ministers. Some had always known freedom, while others were born into slavery. Some were highly educated elsewhere, and others had never been taught to read because the law in Mississippi forbade it. Many came to Mississippi to help build a more just government, and many were driven out by violence only a few years later.

Reconstruction Begins

What was this new political world that made Black men’s rapid rise to power possible? After the Civil War, Southern states like Mississippi, as a condition of being readmitted to the Union, were required under the federal Reconstruction Act of 1867 to enter a period known as Reconstruction, which was intended to integrate freedmen as equal citizens, to restore the allegiance of people who had fought against the United States, and to start rebuilding the South’s devastated economy.

For Reconstruction in Mississippi, 1868 was a significant year. President Andrew Johnson appointed Adelbert Ames as the state’s provisional governor. Ames, a former Union general who was much despised by many White Mississippians and labeled a “carpetbagger,” supported the political enfranchisement of Black men. That same year, three-fourths of the states ratified the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. It recognized the full citizenship of all formerly enslaved people and granted them equal protection under the law. Finally, the Mississippi Constitution of 1868, written by a convention in Jackson of seventy-eight White and sixteen Black men, empowered Black men to vote and, consequently, to hold local, statewide, and national offices. The 1870 ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment solidified on a national level the right of all men to vote, regardless of race.

Because African Americans made up 55 percent of Mississippi’s population, White opposition could not prevent the election of Black men to office. However, it is important to note that Mississippi never had a Black governor nor did African American men ever comprise a majority in the state legislature. The first Black state legislators, elected in the late fall of 1869, took their seats in January of 1870 with five men in the Senate (14 percent) and thirty-five men (47 percent) in the House of Representatives. James D. Lynch had been elected Secretary of State the year before, and Mississippi would soon be sending the first Black man to the U.S. Senate with the election of Hiram Revels. Having enfranchised Black men and created a new constitution, as required by the federal Reconstruction Act, Mississippi was officially readmitted to the United States in February of 1870. “Radical Reconstruction” (a term used by conservative White politicians and journalists to invoke fear and distrust of the progressive Republican faction) had truly begun, and for many people who had been enslaved only a few years before, it was a time of great promise and new opportunity.

Black Representation in the Mississippi Legislature

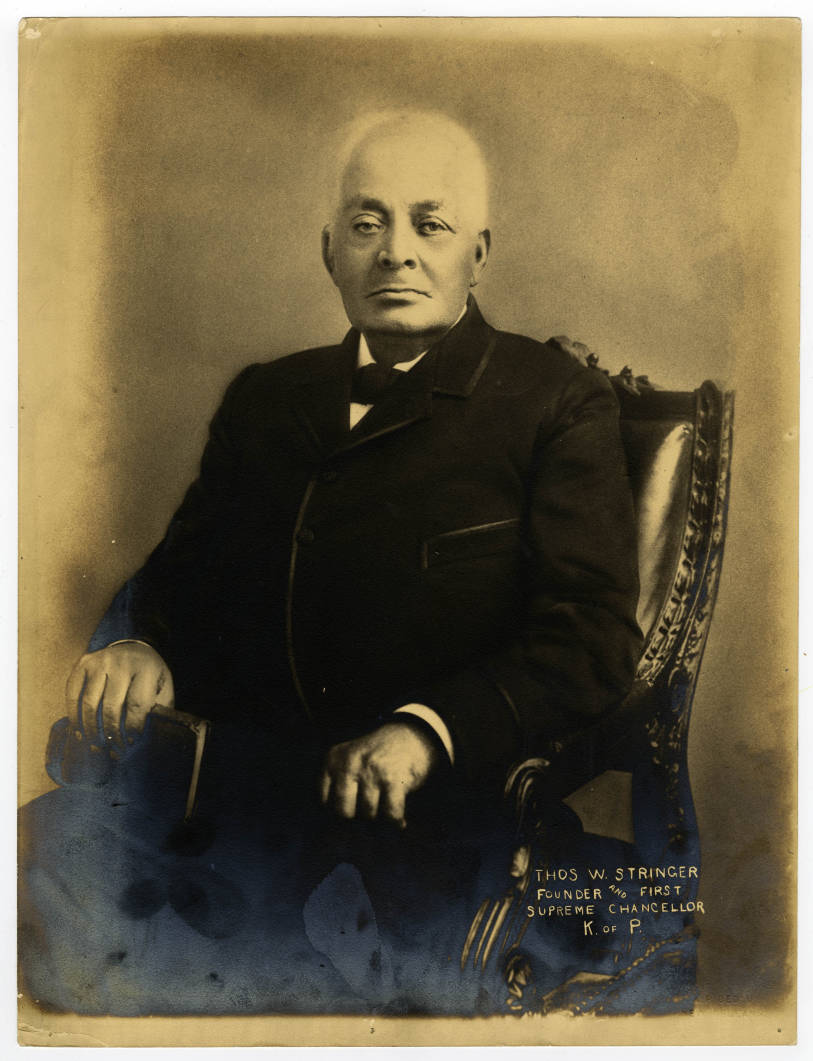

Some of the legislators, such as Isham Stewart of Noxubee County who was first a representative and later a senator, had been enslaved and never had the opportunity to learn to read or write. White newspaper reporters seized upon this fact as evidence of the new legislators’ ignorance and unfitness for office, mocking the men for the very illiteracy that had been forced upon them by law. Many of the first African American legislators had been born free and were educated, including Lowndes County’s Jesse F. Boulden, Madison County’s James J. Spelman, and Warren County’s Thomas W. Stringer, who was a delegate to the 1868 constitutional convention. Others had been born into slavery but nevertheless managed to attain educations for themselves. One example was representative and future lieutenant governor Alexander K. Davis.

In fact, Mississippi’s Reconstruction legislators valued education and made it their top priority. Article VIII of the 1868 constitution established “a uniform system of free public schools, by taxation or otherwise, for all children between the ages of five and twenty-one years.” State senator George Washington Albright of Marshall County later recalled to the Daily Worker in 1937: “Before the Civil War there wasn’t a free school in the state, but under the Reconstruction government, we built them in every county, 40 in Marshall County alone. We paid to have every child, Negro and white, schooled equally.” Whites, too, knew the value of education; schoolteachers, especially those who had come from the North, were frequent targets of threats and violence. In the end, public education in Mississippi would be the most enduring legacy of the Reconstruction legislators.

Another top priority for the new African American officeholders was civil rights. Delegates to the 1868 state constitutional convention were mocked in White newspapers for insisting that journalists refer to them as “Mr.” as they did with White legislators. With their new legislative power, this Republican coalition of legislators passed a civil rights bill in 1873. Hannibal C. Carter of Warren County said of the bill’s passage, as quoted in the New National Era of March 6, 1873: “This is, indeed, the proudest moment of my life . . . I cannot find words to express the feelings of my heart.”

Republican politicians rather quickly divided into two camps during the early 1870s. White men supported more moderate candidates, such as James L. Alcorn, who served as governor from 1870 to 1871 before being appointed to the U.S. Senate. Alcorn was born in the North but moved to Mississippi in the 1840s and enslaved nearly a hundred people. Black men tended to support candidates who pushed for civil rights and demanded more representation in the state’s higher offices, refusing to be pawns for the political advancement of White men.

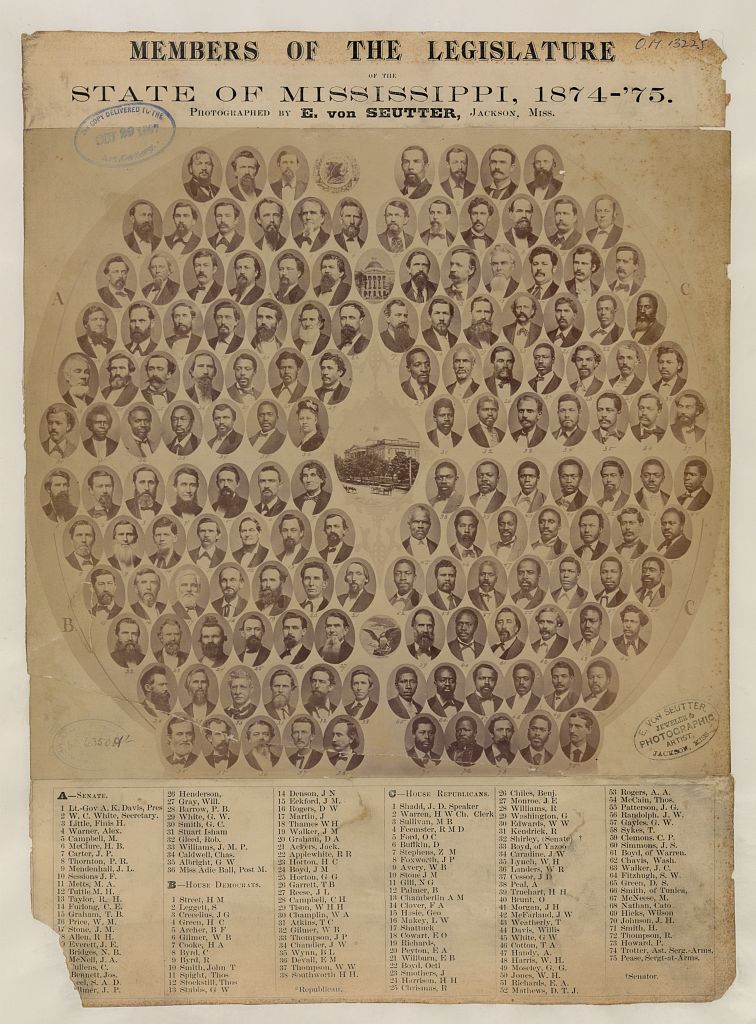

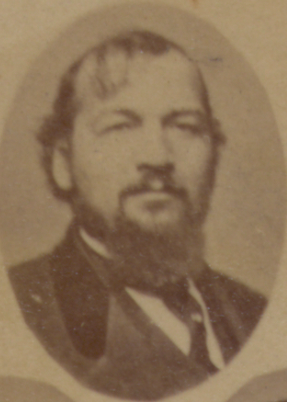

The 1874-75 legislative term saw the height of African American influence in state government. This legislature is the one that elected Branche K. Bruce as the first African American to serve a full six-year term in the U.S. Senate. (Prior to the 17th Amendment ratified in 1913, U.S. senators were chosen by state legislatures.) Adelbert Ames had won another term as governor. Although he was White, this former Union officer and Maine native supported Black political power. Alexander K. Davis of Noxubee County served as lieutenant governor, one of the first Black men in the country to hold this position. James Hill was the secretary of state, a position Black men held in Mississippi from 1869 to 1878. Isaac D. Shadd (brother of the trailblazing journalist, lawyer, and activist Mary Ann Shadd Cary) presided as Speaker of the House. Ten Black men (28 percent) served in the Senate, and fifty-nine (79 percent) in the House of Representatives.

"Redemption" and the End of Reconstruction

The backlash from White Democrats was fierce. As part of their “Mississippi Plan” to regain political control, voter intimidation and violence reached a fever pitch in 1875. The statewide violence peaked with the bloody Clinton riot on September 4 and its aftermath, in which dozens of African Americans were killed. On October 20, James G. Patterson, a teacher and state representative from Yazoo County, was attacked and hanged by a mob after being accused (almost certainly falsely) of hiring a man to commit murder. Before he died, Patterson withdrew some money from his pocket and asked the leader of the mob to promise to send it to his sisters in Ohio, as Patterson was paying for their schooling. According to the Wisconsin State Journal of August 12, 1878, which published a lengthy account of Patterson’s lynching, “Within a week one of the leaders of the crowd of young white gentlemen engaged in this murder, was riding in a new buggy behind a fine horse.”

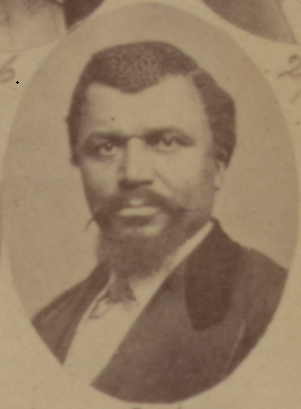

Charles Caldwell, who was formerly enslaved, a delegate to the 1868 constitutional convention, and became a state senator from Hinds County, was assassinated by White vigilante political opponents on December 30, 1875. Caldwell had provided powerful resistance to violent efforts by Democrats to prevent Republicans from voting. It cost him his life. Historian Vernon Lane Wharton described Caldwell as “absolutely fearless,” and historian Buford Satcher recorded this account of Caldwell’s death:

Caldwell went into the town of Clinton to learn about his nephew who had been threatened earlier that day. After dinner he returned to Clinton. This time an acquaintance of his, Buck Cabell, invited Caldwell to drink a toast in celebration of Christmas. While the two men stood in the basement of Chilton’s store, they touched their glasses, apparently a signal for the assassins. Caldwell was shot in the head as he stood with his back to the window. Not quite dead, he lifted himself up and told the assassins not to forget that they were killing a gallant man and that when he was dead be mindful of the fact that he was not a docile man. At that instant, some forty shots rang out, delivering the fatal blow.

So notorious was the violence of the 1875 election year in Mississippi that the U.S. Senate formed a select committee to investigate it. Their final report was published in two volumes totaling more than 2,000 pages of testimony and evidence. But the Democrats, who called themselves the “Redeemers,” had accomplished what they set out to do. When the 1876 legislature was sworn in, Black men held only four seats (11 percent) in the Senate and twenty-four (32 percent) in the House. Lieutenant Governor Alexander K. Davis, the highest-ranking African American officeholder, was impeached on politically motivated charges that he denied, and Governor Ames, also facing impeachment over false allegations, resigned. Reconstruction in Mississippi was effectively over.

From 1876 to 1894, Black representation in the state legislature steadily declined. Governors and other top state officials were all White Democrats. Some Black men managed to win election by crossing over to the Democratic Party, while others joined “Fusion” or “compromise” tickets that mixed Democratic and Republican candidates. Even those who remained with the Republican Party no longer espoused the same views of their counterparts from the early 1870s to protect their safety and that of their families.

George Washington Gayles served as the only Black man in the Senate from 1882 to 1886. Nine Black men served in the House in 1888, six in 1890, and two in 1892 and 1894. There would not be another African American elected to the Mississippi state legislature until Robert G. Clark Jr. won his historic election in 1968.

The 1890 Constitution and the Jim Crow Era

The ratification of the Mississippi Constitution of 1890, which implemented poll taxes and unfairly-applied literacy tests, disenfranchised the vast majority of African American voters in the state. Those who could pay the taxes and pass the literacy tests were kept from the ballot box by intimidation and violence. Prior to this constitution’s adoption, at least 142,000 Black men were registered to vote. By 1892, there were only 8,615. It was not until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that Black people in Mississippi could once again begin to wield their political power—and it was the first time that Black women in the deep South finally had access to the ballot.

Incidentally, the Constitution of 1890 also effectively disenfranchised many poor White men. Prior to its enactment, there were about 110,000 registered White male voters. By 1892, that number fell to just over 68,000.

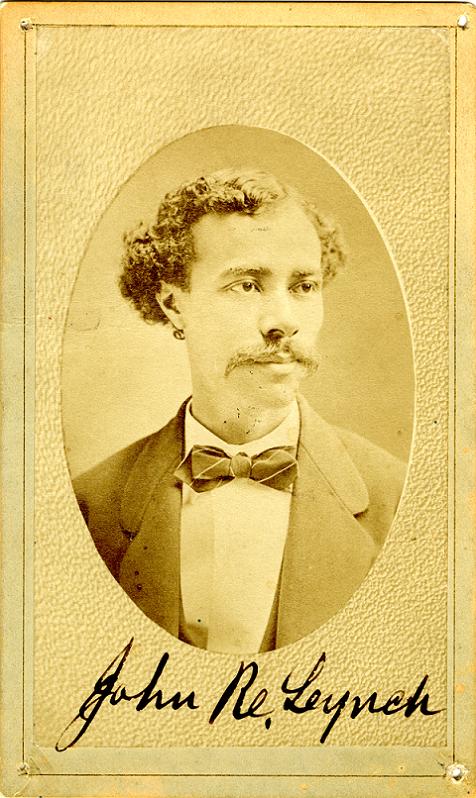

And what became of Mississippi’s first Black legislators? Some, as noted above, were murdered. Many left the state after 1875 to secure safety and better opportunities elsewhere as lawyers, businessmen, educators, ministers, and public speakers. Some remained in Mississippi but left politics to run their farms and businesses out of the dangerous spotlight. Gradually, the “Lost Cause” narrative overshadowed the truth about Reconstruction, especially the accomplishments of African Americans. These narratives portrayed Mississippi’s African American legislators as corrupt and ignorant, robbing the taxpayers, and bankrupting the state. Though John Roy Lynch tried to correct this mythology with his 1913 book, The Facts of Reconstruction, this false narrative persisted and continued to be taught in schools well into the mid- and late twentieth century.

DeeDee Baldwin is the History Research Librarian at Mississippi State University. She created the website, Against All Odds: The First Black Legislators in Mississippi.

Lesson Plan

-

The 1874-75 legislative term saw the height of African American influence in state government. -

Alexander K. Davis became the state’s first African American lieutenant governor before being impeached in 1875 as part of the Mississippi Plan to return government to white Democrats. Photo courtesty of Against All Odds: The First Black Legislators in Mississippi website at Mississippi State University Libraries.

-

Charles Caldwell was a state senator from Hinds County whose assassination in 1875 helped end the promise of Reconstruction. Photo courtesty of Against All Odds: The First Black Legislators in Mississippi website at Mississippi State University Libraries. -

Hiram Revels became the first African American U.S. senator in 1870. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress. -

John R. Lynch was elected Speaker of the House in the Mississippi Legislature and later served in the U.S. House of Representatives. In 1913 he published "Facts of Reconstruction," an inspiration to later revisionist historians. Photo courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Thomas W. Stringer was a delegate to the 1868 Constitutional Convention and later elected as a state senator from Vicksburg. Photo courtesy of Xavier University of Louisiana Library Digital Archives & Collections. -

Blanche K. Bruce was the first African American to serve a full term (1875-1881) in the United States Senate. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Sources:

Baldwin, DeeDee. Against All Odds: The First Black Legislators in Mississippi. 2018, much-ado.net/legislators/. Accessed December 13, 2021.

Behrend, Justin. Reconstructing Democracy: Grassroots Black Politics in the Deep South after the Civil War. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2017.

Bennett, Lerone. Black Power U.S.A.: The Human Side of Reconstruction, 1867-1877. Chicago: Johnson, 1967.

Cabinis, E. W. The Clinton Riot: A True Statement, Showing Who Originated It. Jackson: Democratic-Conservative Executive Committee, 1875.

Foner, Eric. Freedom’s Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders during Reconstruction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993.

Harris, William C. Day of the Carpetbagger: Republican Reconstruction in Mississippi. Louisiana State University Press, 1979.

Journal of the Proceedings in the Constitutional Convention of the State of Mississippi. 1868. Jackson: E. Stafford, 1871.

Lynch, John Roy. The Facts of Reconstruction. New York: Neale Publishing Company, 1913.

Morgan, Albert T. Yazoo: Or, on the Picket Line of Freedom in the South. Washington, D.C.: self-published, 1884.

Satcher, Buford. Blacks in Mississippi Politics 1865-1900. Washington, D.C.: University Press of America, 1978.

Thompson, Patrick H. The History of Negro Baptists in Mississippi. Jackson: R. W. Bailey Printing, 1898.

United States. Congress. Senate. Mississippi in 1875. Report of the Select Committee to Inquire into the Mississippi Election of 1875. Washington: GPO, 1876.

Wharton, Vernon Lane. The Negro in Mississippi: 1865-1890. New York: Harper & Row, 1965.