Mississippi Choctaws have a strong tradition of doing business. As early as 1700, the tribe had developed a strong economy based on farming and selling goods and livestock to the Europeans who were beginning to venture into Choctaw territory. Trade between the Choctaws and other Southeastern tribes had long been established. Throughout the 18th century, the Choctaws were a prosperous people with large land holdings. Their lands spread over what is now central Mississippi.

As the United States of America came into being, however, the expansion of the new nation brought pressures for more land, and the federal government turned its attention to land held by American Indians. Like other Southeastern tribes, the Choctaws were placed in the position of negotiating over their lands. In fact, after the formation of the Mississippi Territory in 1798 and the election in 1800 of Thomas Jefferson to the U. S. presidency, the federal government had an increasing hunger for Choctaw land. President Jefferson issued his military strategy that the federal government acquire all the lands bordering the east side of the Mississippi River for purpose of defense against France, Spain, and England.

Shortly thereafter, in 1801, the Treaty of Fort Adams was signed in which the Choctaws ceded to the United States 2,641,920 acres of land from the Yazoo River to the thirty-first parallel. That was the first in a series of treaties between the Choctaws and the United States. More and more Choctaw land was ceded to the federal government with each successive treaty — between 1801 and 1830, the Choctaw ceded more than 23 million acres to the United States. The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek in 1830 marked the final cession of lands and outlined the terms of Choctaw forced removal to the west. Indeed, the Choctaw Nation was the first American Indian tribe to be evicted by the federal government from its ancestral home to land set aside for them in what is now Oklahoma.

When the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was signed, there were over 19,000 Choctaws in Mississippi. From 1831 to 1833, approximately 13,000 Choctaws were deported to the west in a dangerous journey that many did not survive. More were forced to follow over the years. Those who managed to stay in Mississippi are the ancestors of today's Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.

The promise of land

The ancestors’s decision to remain in Mississippi came at a high cost. The Choctaws who stayed did so because of the promise of land as outlined in Article 14 of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. To remain, Choctaw families or individuals were required to register with the Indian agent within six months after signing of the treaty or be forever barred from registering under Article 14. Each adult who registered was entitled to 640 acres of land; each child over ten who was living with a family was entitled to receive 320 acres, and each child under ten living with a family, 160 acres. Although the Choctaw families who managed to register and be allotted land by the illusive and antagonistic Indian agent, William Ward, many had to sell their property to survive. Consequently, most of the remaining Choctaws were forcibly removed to Indian Territory. Others fell prey to unscrupulous business practices and were cheated out of their property.

At the turn of the 20th century, only 1,253 Choctaws remained in the state and young Mississippi Choctaws had limited choices for the future. There was no recognized tribal government and very few Choctaws owned land. Few schools were open to Choctaw children, and most children were needed to work in the fields alongside their parents. In the decades since forced eviction, Choctaws worked primarily as sharecroppers, with little access to education or basic health care. It appeared that the 20th century would hold the same limited possibilities as the previous century.

The substandard quality of life, lack of educational opportunity, and poor health conditions prompted the U.S. Congress to organize a committee to investigate Choctaw living conditions. The subsequent report described the Choctaws as living in the “poorest pocket of poverty in the poorest state in the country.” Thus, in 1918, the Bureau of Indian Affairs established the Choctaw Indian Agency at Philadelphia, Mississippi, to set up schools and address the poor health conditions among tribal members.

Tribal government

Even with the establishment of the Choctaw Indian Agency, the tribe still had no officially recognized government of its own. A Choctaw government did not come about until the passage of the federal Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. This legislation put an end to nearly five decades in which American Indians were expected to acculturate into non-Indian society. Land which formed the basis for what is now the Choctaw Indian Reservation was purchased and put in trust in 1939.

Tribal members were elected to a temporary tribal council that advised the agency superintendent. The first council was made up of ten tribal members: Bob Henry, Houston Steve, Anthen Johnson, Pat Chitto, Joe Chitto, Billy Nickey, Dempsey Morris, Willie Solomon, Nicholas Bell, and Baxter York. Unlike the modern tribal council, the first council was unable to introduce legislation or appropriate funds. These powers would not be possible until a tribal constitution established a federally recognized tribal government. In 1944, the Choctaws sent a proposed constitution to Washington, D.C. In December of that year, the 15,150 acres purchased for the Choctaw Indian Reservation were set aside for the tribe.

The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians was federally recognized by the United States government in 1945, when the constitution was accepted by the federal government and ratified by vote of the tribal members. The temporary council called an election so that an official council could be selected. Joe Chitto of the Standing Pine Community was the first chairman of the council. The sixteen-member council was elected by the Choctaw people to two-year terms. The council chairman was selected by the council. By this time, the Choctaw Indian Agency was operating elementary schools in most of the Choctaw communities and had built a hospital for tribal members in Philadelphia.

In the mid-1970s, the tribal constitution was amended so that a tribal chief is elected by the people, effectively establishing executive and legislative branches of Choctaw government. At the same time, the term of office for the tribal council members was increased to four years.

Need for job creation

Significant changes to the tribal economy, however, were slow in coming. With the exception of a few tribal members who worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, most Choctaws supported themselves through agricultural work. By the late 1960s, Choctaw council members could see little improvement in the tribe's situation. They knew that the tribe could not rise out of poverty through dependence on the federal government alone, and they began to take steps toward a goal of Choctaw self-determination. By this time, the council had assumed a much more active role in the tribe's affairs.

With unemployment among tribal members a staggering 80 percent, the most pressing need was job creation. To meet this need, the Choctaws took the first steps in a remarkable journey. Chahta Development, a tribal-owned construction company, was established in 1969. Tribal Chief Phillip Martin, then tribal chairman, and the tribal council saw an opportunity when the federal government provided funds to build low-income housing for tribal members. They realized that a tribal-owned construction company could build these houses at a small profit while providing jobs and skills training for Choctaws. Chahta Development set the stage for more progress. “We had to build an economy,” recalled Chief Martin in a 2002 interview, “and we didn't have much to sell except a lot of labor and natural resources.”

In the mid-1970s, many manufacturers were moving production to the South where the workforce was not heavily unionized. The tribe decided to take advantage of this trend, contacting several hundred potential manufacturers. The first to respond was Packard Electric, a division of General Motors. In 1979, the company opened a plant to make wiring harnesses for cars on the reservation.

The availability of labor and tax incentives that included no property taxes and an employee tax credit enticed more businesses to the reservation. American Greetings opened a plant to hand-finish greeting cards. An automotive speaker plant, a direct-mail and printing operation, and a plastic-molding firm followed. By 2002, tribal businesses produced plastic cutlery for McDonald's and wiring components for Club Car, Inc., Caterpillar, and Ford Power Products, among others.

National Indian Gaming Act

Realizing that manufacturing is subject to swings in the economy, the Choctaw leaders sought to diversify the tribe's economy. In the 1980s, they opened a nursing home and shopping center on the reservation. Both operations serve clients and customers from surrounding communities as well as from the reservation. By 1990, the tribe had developed a diversified economy that included manufacturing, retail, service, and government jobs.

Next came the tribe's most ambitious development. The U.S. Congress passed the National Indian Gaming Act in 1988. The law enables federally recognized tribes to operate casinos on reservations after negotiating a compact with states. The Choctaws opened the Silver Star Resort and Casino in 1994. The only land-based casino in Mississippi, the Silver Star in 2002 employed more than 2,000 people and provided revenue that supported an array of tribal programs. With the goal of a diverse economy firmly in mind, the Choctaws used the Silver Star's success as a springboard into the tourism industry.

Dancing Rabbit Golf Club opened in 1997 and features an award-winning 18-hole golf course and club house. A second golf course was added two years later. These forays into the tourism industry proved to be beneficial to the tribe and spurred the chief and tribal council to implement the development of a destination resort to attract more visitors to the reservation. Thus, the summer of 2002 saw the opening of Geyser Falls Water Theme Park and the Golden Moon Hotel and Casino. Projects under development then included a 280- acre recreational lake, a fitness and wellness center, more hotels, retail shopping, and additional golf courses. The tribe also established the Choctaw Hospitality Institute to train workers for the casinos and other resort enterprises.

The Choctaw community

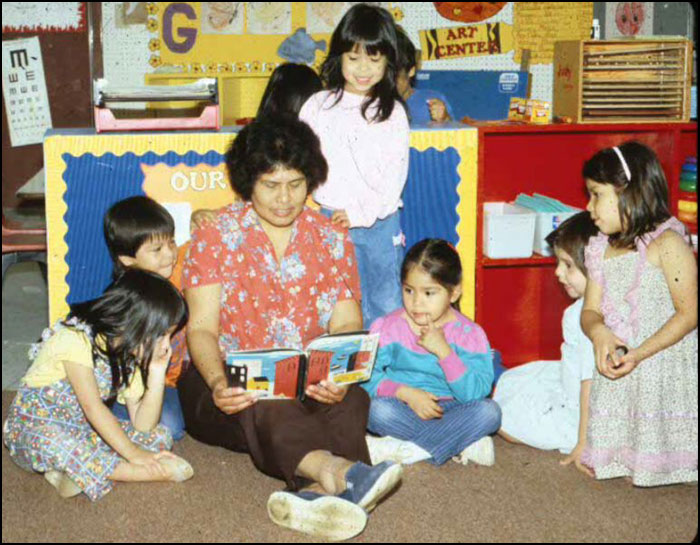

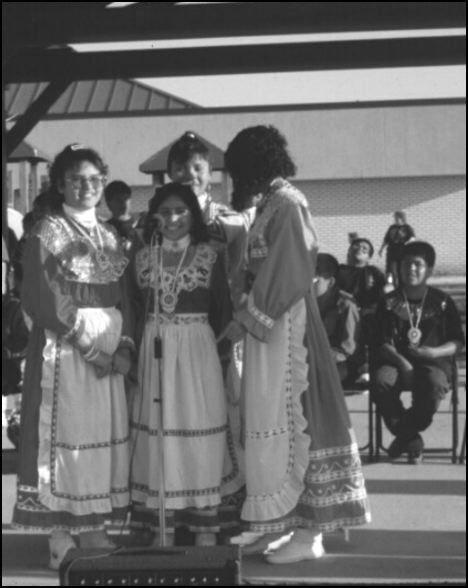

The benefits of the tribe's aggressive economic development efforts extended beyond job creation. Revenue from its business ventures has enabled the tribe to build up its social and health care services, build schools and day care centers, and provide post-secondary education for tribal members. Economic success has also strengthened the traditions and culture of the Choctaw community. The Choctaw language is still spoken by most adults on the reservation, but younger tribal members are less likely to be fluent in the language. Other traditions, such as Choctaw social dance and swamp-cane basketry are still a part of Choctaw life. Tribal members often wear traditional clothing for special occasions. Revenue-funded programs conduct research and lead workshops in the Choctaw language and traditional crafts and skills, underscoring perhaps the biggest benefit of the tribe's success. It has given young Choctaws a reason to stay in tribal communities by creating a wide range of job opportunities and by providing an educational structure to prepare tribal members for the jobs that exist. As a result, tribal members hold professional positions in education, law enforcement, social services, health care and business. “If we separated, everybody going their own way, the culture would die,” Chief Martin told a reporter from USA Today in 2002.

For most of the 20th century, young Choctaws had to choose between leaving their families and tribe or facing an uncertain future on the reservation. In the 21st century, their children and grandchildren can stay on the land their ancestors refused to leave and be part of a thriving, forward-looking economy. Indeed, at the dawn of the 21st century, conditions could not have been more different from the turn of the 20th century.

In 2002, the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians is one of the state's largest employers, operating 19 businesses and employing more than 7,800 people, not all of them tribal members. Tribal operations indirectly generate an additional 5,482 permanent jobs in Mississippi. See additional economic information.

If 19th century Choctaws could visit their homeland in the 21st century, they would be both amazed and proud – amazed at the diverse tribal economy, high employment, and burgeoning tribal infrastructure and proud of the determination and effort that made these changes possible.

Deborah Boykin is tribal archivist for the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.

Posted December 2002