Gideon Lincecum moved to Mississippi in 1818. He brought his family, which included his wife Sarah Bryan, two small children, his parents, some siblings, and a few enslaved African-Americans. They settled initially along the Tombigbee River and helped establish the town of Columbus, Mississippi.

The Lincecums were part of the hundreds of other new settlers traveling west from the Carolinas, Georgia, and Alabama during the first two decades of the 19th century. The number of Americans moving west then was so great that historians refer to the movement as the Great Migration.

Like those other settlers, Lincecum, a Georgia native, arrived seeking a new life and new opportunities to make a living and support his family. He was a man of many talents. While living in Mississippi, Lincecum cut and sold lumber, hunted, traded merchandise with Choctaw and Chickasaw Indians, and organized a tour of Choctaw stickball players in exhibition games. He served as chief justice of the “Quorum,” a group of people appointed by the Mississippi Legislature to organize Monroe County, was chairman of the school commissioners, and superintendent of the new male and female academies in Monroe County. He dabbled in medicine before becoming a full-time doctor in 1830.

He and his family remained in Mississippi for 30 years, for a while living farther north up the Tombigbee River near Cotton Gin Port. In 1848, he moved his family to Texas in search of new borders and new opportunities.

The hunter

To Lincecum and his family, one of the main attractions of the Tombigbee River region, located in eastern Mississippi, was the vast quantities of wildlife. Like many Mississippians of today, Lincecum loved to hunt for sport and to provide food and income for his family. Lincecum quickly made friends with some neighboring Choctaw Indians and frequently hunted with them.

He observed with wonder the countless deer, bears, turkeys, ducks, and fish, writing about his family’s early days in Mississippi that “we were all greatly pleased, and supplied our table with a superabundance of fish, fowl, and venison, and occasionally a glorious fleece [meat taken from either side of the hump] of bear meat. The quantity of game that was found in that dark forest and the canebrakes was a subject of wonder to everybody.”

Lincecum reported that he killed upwards of 400 deer during his early years in Mississippi, selling their dried hams to boatmen on the Tombigbee River. Packs of wolves also inhabited the region at that time, coming so near to the Lincecum camp that they “could hear them snapping their teeth.”

Enlightened thinker

Lincecum was a busy man willing to try various activities to secure an income and support his family. In this respect he was much like the hundreds of other new immigrants to Mississippi in the first few decades of the 1800s. But in many ways Lincecum was not a typical early American settler. His views on education and religion reflected the Enlightenment ideals of the American founders more than the evangelical patterns of many of his Mississippi neighbors. Even though he was largely self-taught, having learned to read and write and do basic math largely on his own as a youth, Lincecum was a “frontier intellectual” who read constantly and valued education highly.

He wanted his ten children to receive the best possible schooling, but that was difficult in the frontier setting of early 19th-century Mississippi. In 1831, while living in Cotton Gin Port, he enrolled six of his children in the only available school, a “highly lauded seminary” in Columbus. Lincecum traveled to Columbus six months after his children started their studies in order to find out how much they had learned. His children told him they had mastered history and geography; however, they could not tell their father what sort of history they now knew, nor could they name the principal rivers in the state of Mississippi or in the United States.

Bewildered and fearing that he had wasted money, Lincecum asked his sons and daughters to tell him what they had learned. Their answers revealed that they had been taught only Bible stories and little else. Lincecum was appalled: “I was overwhelmed with disappointment. I felt that the whole world was a sham. My children, after six months’ constant attendance in that highly praised institution, could answer no questions of use. But they had been put on the road to salvation ... .”

He immediately pulled his children out of the school and took them back to Cotton Gin Port. Apparently Lincecum relied on home schooling for his children from that point onward. Throughout his life Lincecum remained a committed free thinker and critic of organized religion.

The doctor

Lincecum had studied medicine on his own since 1811, and had periodically provided medical services for his neighbors and other customers. As with education, Lincecum’s views on medicine reflected a willingness to question the established truths of his day and to seek out more practical methods for healing people. In 1830, Lincecum became a full-time doctor near Cotton Gin Port in order to make an income without doing strenuous work, for he had become very sick after physically over-exerting himself. Lincecum practiced allopathic medicine which relied heavily upon bleeding the patient and administering strong drugs, such as mercury.

People in early 19th-century Mississippi often caught illnesses. Lincecum wrote that “one or more of the family was sick all the time.” When Lincecum and other Mississippi doctors lost hundreds of patients during a cholera outbreak around 1833, Lincecum became convinced that the medical books of his day did more harm than good, especially the practice of “bleeding” patients to release impurities. “I felt tired of killing people,” he exclaimed, “and concluded to quit the man killing practice.” Lincecum complained that all American medical journals at the time were written by people in the northern states who did not understand southern diseases or the southern environment.

He sought out an expert on southern illnesses who knew herbal remedies for most ailments. That expert was a Choctaw doctor called Alikchi Chito (“Great Doctor”) who lived in the Six Towns Division of the Choctaw Nation (the Six Towns, located in the southern region, was one of three ethnic and political divisions among the Choctaws, the other two were called by the Americans the Western and Eastern divisions). Over a period of six weeks, Alikchi Chito taught Lincecum the uses of various plants to cure most types of sickness. From that point onward, Lincecum rejected the so-called remedies published in medical books in favor of herbal medications to treat his patients and called himself a “botanic doctor.”

His new medicines worked beyond his expectations and he enjoyed a reputation as a very good doctor the remainder of his time in Mississippi. Herbal remedies are popular today and have always been used in so-called “folk medicine” by various Mississippians. The notable aspect of Lincecum’s medical training is that he learned the most effective medicines from Choctaw and then passed on that knowledge to his patients and other doctors, thus preserving a key aspect of the cultural practices of the original inhabitants of Mississippi.

Friend of Indians

Lincecum interacted with Choctaw and Chickasaw frequently before most of the Native Americans were forcibly removed in the early 1830s by the Mississippi and United States governments. He traded with them, hunted with them, ate meals with them, sought out their knowledge about medicine, learned how to speak and write their language, organized and led a tour of Choctaw stickball players throughout the South in 1829-30, and familiarized himself with much of their history and traditions.

Lincecum visited an elderly Choctaw man called Chahta Immataha several times between 1823 and 1825 in order to record the traditional history of the Choctaws. In 1904, the Mississippi Historical Society published parts of that long story, but Lincecum’s entire written history of the Choctaw people, based on what Chahta Immataha told him, exists in the University of Texas Archives.

Lincecum knew Choctaw Chief Pushmataha personally and wrote the most valuable description of his life that exists. Unlike many of his early 19th-century Mississippi neighbors, Lincecum viewed Native Americans as people worthy of respect who were every bit equal, and often superior, to Euro-Americans. Where Native Americans had problems, such as with alcohol abuse, Lincecum tended to blame the bad influence of non-natives for the situation.

Though overly romantic, Lincecum felt that Native Americans were the most honest and decent people he had ever met. He even suggested that “if there could be born an honest, liberty-loving leader who would take things in hand, concentrate the Indian forces, capture all the praying white races and their allies, the mixed-blood cut throats, and chop off their ... heads, there would remain the most innocent law-abiding people on earth — the pure Indian.”

As the Mississippi and U.S. governments forced Native American removal west of the Mississippi River in the early 1830s, Lincecum sympathized with the anti- removal position of most Choctaws and Chickasaws. He singled out the various Christian missionaries living and working among the natives for particular condemnation, believing they did little to stop Indian Removal. Lincecum eloquently described his feelings towards his Native American neighbors when remembering a Choctaw family that passed his home on their way to banishment in Indian Territory in November 1831:

“I remember now, though the time has long passed, with feelings of unfeigned gratitude the many kindnesses bestowed on me and my little family in 1818 and 1819 when we were in their neighborhood, before the country began to fill up with other white people ... . We met often, hunted together, fished together, swam together, and they were positively and I have no hesitation in declaring it here, the most truthful, most reliable and best people I have ever dealt with. While we resided in their country my wife had a very severe spell of fever that confined her to bed for several weeks ... kind hearted Chahta women would come often, bringing with them their nicely prepared tampulo water for her to drink, and remaining by the sick bed for hours at a time ... . The time is long gone, and I may never have the pleasure of meeting with any of that most excellent race of people again. But so long as the life pendulum swings in this old time-shattered bosom, I shall remember their many kindnesses to me and mine, with sentiments of kindest affection and deepest gratitude.”

Legacy

Gideon Lincecum’s legacy to Mississippi is extensive though it has been under-appreciated. He and his family lived in Mississippi for thirty years and prospered under trying circumstances. Lincecum wrote a detailed autobiography that exposes what life was like in the early years of Mississippi statehood as few other sources can. Some of the most valuable information we have about the Choctaw comes from Lincecum’s writings.

Many historians have noticed the significance of Lincecum’s writing, but Lincecum has not yet been recognized as a key figure in Mississippi history despite the fact that three key Lincecum works were published by the Mississippi Historical Society in the early 20th century.

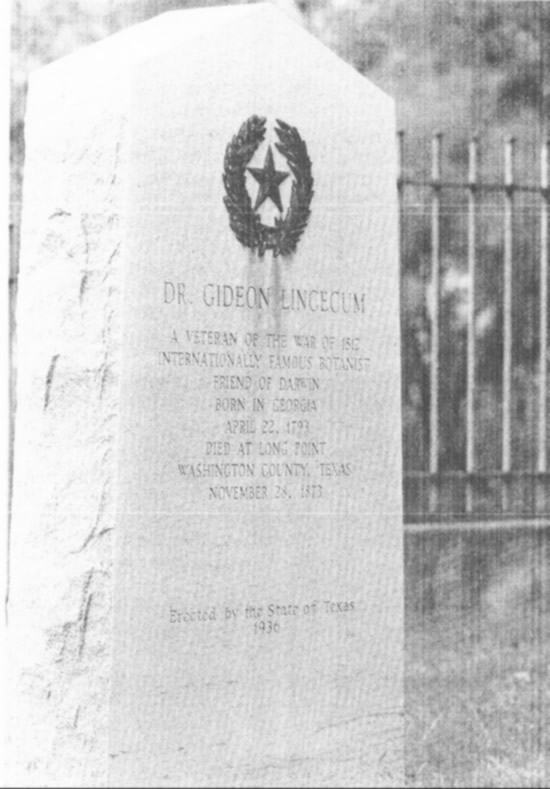

One reason for this neglect is that Lincecum and his family moved to Texas. In Texas, Lincecum became renown as a naturalist. He collected plant and animal specimens, corresponded with notable naturalists such as Charles Darwin (sending him forty-eight samples of Texas ants with detailed commentaries), dabbled in geology, recorded weather observations, and tracked drought cycles.

All of Lincecum’s work published in his lifetime occurred after he moved to Texas. He contributed plant and animal collections to the Philadelphia Academy of Science and the Smithsonian Institution. He wrote articles for the American Naturalist, the American Sportsman, the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences, the Journal of the Linnaean Society, the Texas Almanac, and newspapers.

Lincecum has left a rich record of Mississippi life during a time of massive change and transformation when Mississippi transitioned from Native American to Euro-American control and when frontier lifestyles became increasingly dominated by plantations, large-scale agriculture, and overwhelming dependence on African- American enslavement.

Mississippi is fortunate that a person of Lincecum’s high intellect chose to call Mississippi home and to write about all that he saw and did.

Greg O'Brien, Ph.D., is associate professor of history at the University of Southern Mississippi. He is the author of Choctaws in a Revolutionary Age, 1750-1830 (University of Nebraska Press, 2002) and co-editor of George Washington's South (University Press of Florida, 2004).

Lesson Plan

-

1873 photograph of Gideon Lincecum.From “Adventures of a Frontier Naturalist: The Life and Times of Dr. Gideon Lincecum,” with the permission of Texas A&M University Press. -

In 1905, the Mississippi Historical Society published Lincecum’s autobiography. View the larger image to read an excerpt. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Reference No. B L62L

-

The State of Texas erected memorial to Gideon Lincecum in 1936. The inscription reads in part: “A veteran of the War of 1812 / internationally famous botanist / friend of Darwin.” Photo by Peggy A. Redshaw. From “Adventures of a Frontier Naturalist: The Life and Times of Dr. Gideon Lincecum,” with the permission of Texas A&M University Press.

Sources

Burkhalter, Lois Wood. Gideon Lincecum, 1793-1874: A Biography. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1965.

Davis, William C. A Way Through the Wilderness: The Natchez Trace and the Civilization of the Southern Frontier. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995.

Geiser, Samuel Wood. Naturalists of the Frontier. Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1937.

Lincecum, Gideon. Adventures of a Frontier Naturalist: The life and Times of Dr. Gideon Lincecum. Edited by Jerry Bryan Lincecum and Edward Hake Phillips. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 1994. (http://www.tamu.edu/upress or 800-826-8911)

Lincecum, Gideon. “Autobiography of Gideon Lincecum.” Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society. 8 (1905), 443-519.

Lincecum, Gideon. “Choctaw Traditions about Their Settlement in Mississippi and the Origin of Their Mounds.”Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society. 8 (1904), 521-542.

Lincecum, Gideon. “Life of Apushimataha.” Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society. 9 (1906), 415-485.

Lincecum, Gideon. Pushmataha: A Choctaw Leader and His People. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

Lincecum, Gideon. Science on the Texas Frontier: Observations of Dr. Gideon Lincecum. Edited by Jerry Bryan Lincecum, Edward Hake Phillips, and Peggy A. Redshaw. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 1997.

Oakes, James. The Ruling Race: A History of American Slaveholders. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1982, pp. 55-57.