John Law Glossary

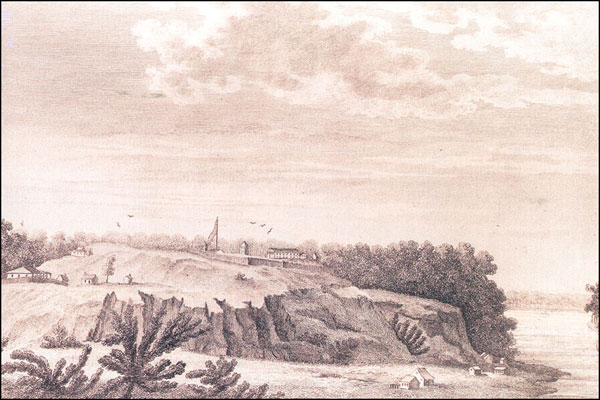

In the early 18th century the economy of France was depressed. The government was deeply in debt and taxes were high. In addition, the French controlled the colony of Louisiana, a vast settlement in the interior of North America. The Louisiana Colony included the Natchez district and the area along the Mississippi Gulf Coast in present-day Mississippi. France was the first European country to settle this area of North America (1699-1763).

The American land was much larger than France and the French knew little about it. Many did not even know where it was. But many had heard the rumor that this land was rich in silver and gold, the French currency.

The depressed French economic environment was fertile ground for some of the monetary and economic ideas of John Law (1671-1729). Law was a Scottish financier born in Edinburgh. He was a colorful character who has been described as tall, handsome, and vain. He had a passion for women and gambling.

When Law came to France in 1714, he renewed his acquaintance with the nephew of King Louis XIV, the Duke of Orleans. The duke became Regent of France after the king's death in 1715. The regent served as ruler while the heir to the throne, five-year-old Louis XV, was still a minor. The duke recalled Law's financial prowess and sought his advice and assistance in straightening out France's financial mess left over from years of reckless spending under Louis XIV.

This association with the Duke of Orleans would ensure Law's place in history. Not only would Law advance the use of paper money, the French word millionaire would come into use as a result of his most famous scheme — the Mississippi Company.

In 1716 Law convinced the French government to let him open a bank, the Bank Generale, that could issue paper money, or bank notes. The paper notes would be supported by the bank's assets of gold and silver and would circulate as a medium of exchange. Paper money was a new concept for the French; money to them was silver and gold. Law believed that paper notes would increase the money in circulation, which, in turn, would increase commerce. These conditions would help revitalize and rehabilitate the finances of the French government.

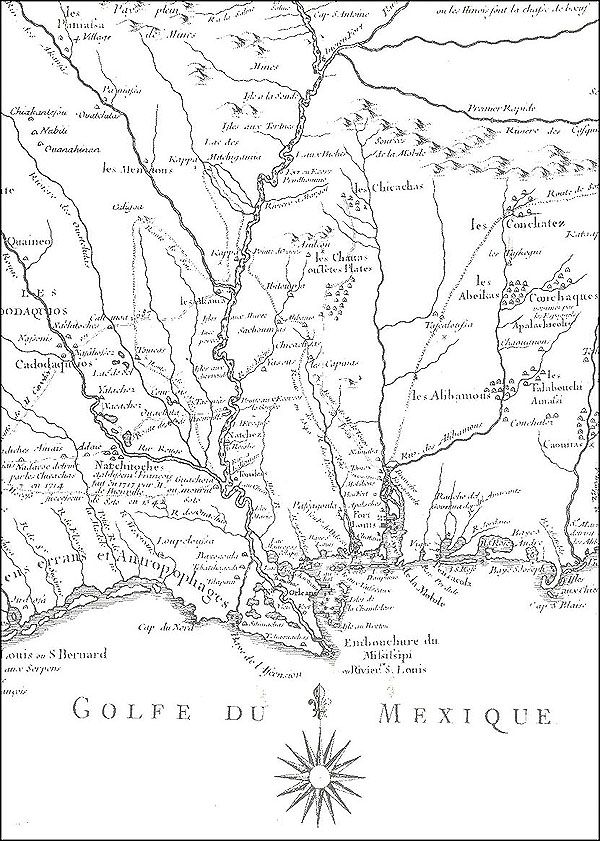

In August 1717, he organized the Compagnie d'Occident (Company of the West) to which the French government gave the control of trade between France and its Louisiana and Canadian colonies. In Canada, the French would trade in beaver skins. In the Louisiana colony they would trade in precious metals.

The colony stretched for 3,000 miles from the mouth of the Mississippi River to parts of Canada. It included the present-day states that hug the river: Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. The colony of Louisiana's connection to the Mississippi River gave rise to the company's more popular name, The Mississippi Company.

Law's company had exclusive trading privileges in the territory for twenty-five years; it could appoint its own governor and officers in the colony and make land grants to potential developers. In turn, the company accepted the responsibility of transporting 6,000 settlers and 3,000 enslaved people to the colony before expiration of its charter.

The scheme to finance the initial operations of the Mississippi Company was simple. Law would raise the money by selling shares in the company for cash and, more importantly, for state bonds. Law accepted a low interest rate on the bonds which helped French finances while promising the company a more secure cash flow. Simply put, Law came up with a way to finance a big business scheme. The lure of gold and silver brought out many eager investors in the Mississippi Company.

Later Law would create cash flow from new economic activity. It turns out that the Mississippi Company was a small part of a much grander empire he was about to create. In September 1718 the company acquired the monopoly in tobacco trading with Africa. Law's Bank Generale was taken over by the French government in January 1719 and was renamed the Bank Royale. Law remained in charge, however, and the crown further guaranteed the bank's note issue. In May he obtained control of the companies trading with China and the East Indies. He renamed his entire business interest the Compagnie des Indes, but most people still called it the Mississippi Company. In effect, Law now controlled all trade with France and the rest of the world outside of Europe.

The company next purchased the right to mint new coins for France, and by October it had purchased the right to collect most French taxes. In January 1720, Law became the Controller General and Superintendent General of Finance. Law now controlled all of France's finance and money creation. He also controlled the company that handled all of France's foreign trade and colonial development. Furthermore, by holding much of the French government's debt, he had created a stable source of income for future business ventures. Law had created Europe's most successful conglomerate.

Law paid for these activities and privileges by issuing additional shares in the company. These shares could be paid for with bank notes (from his bank) or with government debt.

The value of shares in the Mississippi Company rose dramatically as Law's empire expanded. Investors from across France and Europe eagerly played in this new market. The financial district in Paris became so agitated at times with investors that soldiers would be sent in at night to maintain order. Shares in the Mississippi Company started at around 500 livres tournois (the French unit of account at the time) per share in January 1719. By December 1719, share prices had reached 10,000 livres, an increase of 1900 percent in just under a year. The market became so seductive that people from the working class began investing whatever small sums they could scrape together. New millionaires were commonplace.

The weak spot in Law's scheme was his willingness to issue more bank notes to fund purchases of shares in the company. Stock prices began falling in January 1720 as some investors sold shares to turn capital gains into gold coin. To stop the sell-off, Law restricted any payment in gold that was more than 100 livres. The paper notes of the Bank Royale were made legal tender, which meant that they could be used to pay taxes and settle most debts. The company was trying to get people to accept the paper notes rather than gold. The bank subsequently promised to exchange its notes for shares in the company at the going market price of 10,000 livres. This attempt to turn stock shares into money resulted in a sudden doubling of the money supply in France. It is not surprising then that inflation started to take off. Inflation reached a monthly rate of 23 percent in January 1720.

Law devalued shares in the company in several stages during 1720, and the value of bank notes was reduced to 50 percent of their face value. By September 1720 the price of shares in the company had fallen to 2,000 livres and to 1,000 by December. The fall in the price of stock allowed Law's enemies to take control of the company by confiscating the shares of investors who could not prove they had actually paid for their shares with real assets rather than credit. This reduced investor shares, or shares outstanding, by two-thirds. By September 1721 share prices had dropped to 500 livres, where they had been at the beginning.

The rise and fall of the Mississippi Company became known as the Mississippi Bubble. Indeed, Law is most famous, or perhaps infamous, for his involvement in this prominent financial disaster. A “bubble” in the world of finance is a term applied to an unusually rapid increase in stock prices or the value of some other asset such as real estate. The increase is then followed by an equally rapid collapse in prices. The wild fluctuations in prices are usually viewed as irrational and the product of uncontrolled speculation rather than sensible investment practices. The dramatic increase in the NASDAQ stock index, primarily technology stocks, in 1999-2000 and its subsequent collapse in 2000-2004 is sometimes presented as a recent example of a bubble.

Economists are divided on how to interpret Law's scheme. Charles Kindleberger, an economic historian at Yale University, believes Law's intentions were legitimate and that the Mississippi Company was intended to be a real enterprise. Law's financial arrangements, however, were misguided. Others have noted that Law did help straighten out the convoluted system of French taxation and finance. And, the economist Peter Garber believes that Law's system had more potential than is often believed.

The story of John Law and the Mississippi Company is as intriguing as any modern financial disaster. In the end, many of the new millionaires were financially destroyed. So was France. It would be eighty years before France would again introduce paper money into its economy.

Meanwhile, France maintained control of the Louisiana colony until 1763 when it lost the Seven Years' War to the United Kingdom of Great Britain. At the Paris Conference in 1763, all of Louisiana east of the Mississippi River, except the Isle of Orleans, went to Great Britain. Louisiana west of the Mississippi and the Isle of Orleans went to Spain. Spain returned its territory to France in 1800 through a secret deal in which the French, under Napoleon Bonaparte, promised to set up Spanish rule in Italy. In 1803, the United States, under Thomas Jefferson, purchased the territory from France in a deal known as The Louisiana Purchase.

Jon Moen, Ph.D., is professor of business administration, School of Business Administration, University of Mississippi.

References:

Peter Garber, “Famous First Bubbles,” in Speculative Bubbles, Speculative Attacks, and Policy Switching, Robert Flood and Peter Garber, eds. (MIT Press: Cambridge MA, 1994)

Charles Kindleberger, A Financial History of Western Europe, 2nd ed. (Oxford University Press: New York 1993).

Charles Kindleberger, Manias, Panics, and Crashes, 3rd ed. (Wiley: New York 1996).

Charles Mackay, The Mississippi Scheme (Andrew Pub. Co.: 1980).

Joseph Schumpeter, The History of Economic Analysis (Oxford University Press: New York 1954).