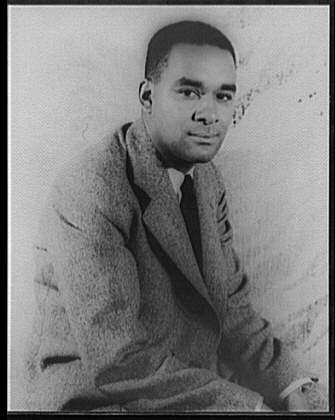

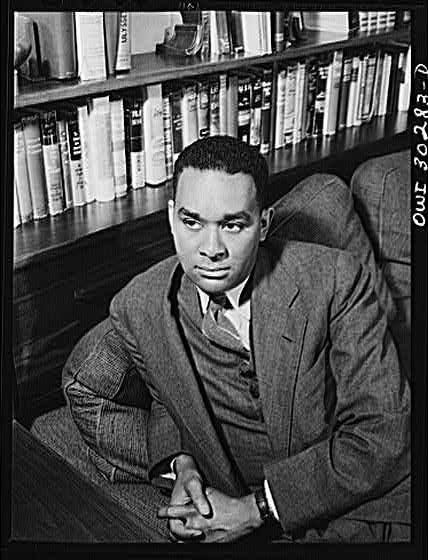

Mississippi has produced more world-class writers than other states in the South and among them is Richard Nathaniel Wright, an internationally acclaimed African American novelist and social critic. Wright, the son of a sharecropper father and a high-school-teacher mother, was born September 4, 1908, on a Mississippi plantation some twenty miles from Natchez.

His parentage shaped his thinking and writing: His father was the laborer, the hands that worked in the soil, the person who deals with the concrete materials of life; his mother was the thinker, the mind that journeys in realms of abstract ideas and imagination. Wright combined the best of both parents.

The quest for liberation

From his birth in Mississippi to his death in Paris on November 28, 1960, Wright was condemned to make a long and unfinished quest for liberation from prejudice.

The power of Wright’s work comes, in part, from his ability to articulate the idea of hunger. During his boyhood, Wright’s hunger was often physical. His father’s desertion of the family when Wright was only seven years old forced his mother to take low-paying jobs to support her sons, Richard and Leon Alan. The lack of sufficient food and the absence of his father became interchangeable in the boy’s mind.

As a man of thirty-seven, Wright reflected on his childhood and youth in Mississippi and other parts of the South in his autobiography Black Boy (1945). He exposed the pain of memory in words that are haunting: “As the days slid past, the image of my father became associated with my pangs of hunger, and when I felt hunger I thought of him with a deep biological bitterness.”

The pain of memories

Wright’s bitterness, however, is directed not only against his father but also against a whole society that allowed and caused hunger among poor sharecroppers. He had painful memories of the South in the early 20th century. The laws of Mississippi supported segregation. Racial customs in the state promoted what Wright called “the ethics of living Jim Crow.” Jim Crow ensured that the ceiling of possibilities for a sensitive, brilliant Black boy was quite low.

Society and culture created a vast need for fulfillment in Wright’s young life. His hunger to develop as a whole human being was at once physical, psychological, social, and spiritual. Such hunger to be, to know, and to understand was pervasive, formative, and motivating throughout his lifetime.

Like many of his peers, Wright migrated to Chicago in the late 1920s. He was part of a large-scale movement of people who sought higher wages, relief from racial oppression, and a chance to make a fresh start. Although as a teenager Wright had published a short story in a Jackson, Mississippi, newspaper, his real success as a writer came with the publication of his stories about rural Southern life in Uncle Tom’s Children (1938).

The hunger of the spirit

His fame as an American writer was assured with the appearances of his landmark novel Native Son (1940) and his poignant autobiography Black Boy (1945). Yet, literary fame, financial security, and his acclaim as a spokesman for an entire generation of African Americans, were not enough to satisfy the hunger that was a driving force in Wright’s life. Material success only served to intensify Wright’s awareness that hunger of the spirit is implacable. He could write passionately and eloquently about the meaning of suffering in the lives of oppressed people, because that suffering was so integral a part of his life. Suffering was a psychological wound that would never heal.

“I sat alone in my narrow room, watching the sun sink slowly in the chilly May sky. I was restless. I rose to get my hat; I wanted to visit some friends and tell them what I felt, to talk. Then I sat down. Why do that? My problem was here, here with me, here in this room, and I would solve it here alone or not at all. Yet, I did not want to face it; it frightened me. I rose again and went out into the streets. Halfway down the block I stopped, undecided. Go back…I returned to my room and sat again, determined to look squarely at my life.

Well, what had I got out of living in the city? What had I got out of living in the South? What had I got out of living in America? I paced the floor, knowing that all I possessed were words and dim knowledge that my country had shown me no examples of how to live a human life. All my life I had been full of a hunger for a new way to live…” [excerpt from Black Boy]

For a period of less than ten years, Wright was a member of the American Communist Party. At first he thought the party had the answers, but later he became disillusioned and renounced his membership. Wright’s exposure to Marxist thought broadened his global vision and made him an especially keen observer of humanity’s plight in the 20th century. On the other hand, Wright never abandoned the perspective he gained as a Mississippian, a Southerner, a man uniquely equipped by his experiences in an unjust world to be a participant-observer of the human condition.

The meaning of being human

In the books that followed Black Boy, Wright expressed his deepening interest in larger questions regarding power, authority, and freedom. Like the protagonist of his novel The Outsider (1953), published after he chose to exile himself in France, Wright felt a profound need to explore the meaning of being human. The novel can help us to understand why Wright felt so obligated to make himself part of the action or to be intrusive, even in works of non-fiction. It helps us to understand, too, Wright’s sustained interest in modern psychology. The Outsider illuminates how hunger to be free from racial discrimination acts as a creative force in the art of writing. At one stage of his thinking about the possibility of being “free of all responsibilities of a certain sort,” Cross Damon, the protagonist of The Outsider wonders what environment would allow such freedom:

“Where could he find such experiences, such spheres of existence? In the main, he accepted the kind of world that the Bible claimed existed; but, for the sufferings, terrors, accidental births, and meaningless deaths of that world, he rejected the Biblical prescriptions of repentance, prayer, faith and grace. He was persuaded that what started on this earth had to be rounded off and somehow finished here.”

Indeed, the environment for absolute freedom is only to be discovered in the new worlds the imagination can create through writing. Whether he was analyzing the independence movement in West Africa in Black Power (1954), reporting on the Bandung Conference (a debate among Asian and African nations about their futures in a global order) in The Color Curtain (1956), examining the political and religious aspects of a Catholic culture in Pagan Spain (1957), or issuing warnings about modernization in White Man, Listen! (1957), Wright was never truly the distanced observer. He was always the engaged writer, the brother-in-suffering.

The return to the familiar

In the later years of his life, some critics accused him of having lost touch with his homeland and racial progress in America. The Long Dream (1958), the last novel published in his lifetime, Wright returns to the familiar landscape of Mississippi to work out themes that were at once personal and racial. Living in Paris in the 1950s, Wright did not have to deal directly with the trauma of the movement to desegregate institutions in the United States. By setting The Long Dream in Mississippi, Wright obligated himself to deal with the effects of dehumanizing laws and customs as he had done in Black Boy. The young hero of The Long Dream leaves Mississippi to find a new life in Paris. During his flight across the Atlantic Ocean, he thinks of the effect Jim Crow has had on his life:

“He had fled a world that he had known and that had emotionally crucified him, but what was he here in this world whose impact loosed storms in his blood? Could he ever make the white faces around him understand how they had charged his world with images of beckoning desire and dread? Naw, naw…No one could believe the kind of life he had lived and was living.

.... Above all, he was ashamed of his world, for the world about him had branded his world as bad, inferior. Moreover, he felt no moral strength or compulsion to defend his world. That in him which had always made him self-conscious was now the bud of a new possible life that was pressing ardently but timidly against the shell of the old to shatter it and be free.” [excerpt from The Long Dream]

The surface story in The Long Dream is about Rex Tucker’s coming of age in Clintonville, a place that is rather like Natchez. The real story in the book is about parents and children, racial interactions, the hidden machinery of business, and the death of innocence. Family, order and disorder, economics, and the burdens of adulthood are themes in much of Wright’s work. The Long Dream unites all of these themes. The book suggests that Mississippi is a paradox: a stage for nightmare dramas and a locale where dreams can emerge and bloom.

Richard Wright, Mississippi’s native son, has left a legacy of challenging works. He was a realist, a writer capable of delivering strong critiques of human failings and human potentials with wry humor and vivid images. His work challenges readers to observe carefully. Whether his works deal with the rural South or the urban North, the foibles of fictional characters or the motives of leading figures in world affairs, Wright was always very Southern in his insistence that his readers must know history. In part to satisfy his own hunger, Richard Wright created a body of literature from which readers might, as he put it in Black Boy, “win some redeeming meaning for their having struggled and suffered here beneath the stars.”

Jerry W. Ward, Jr. is Lawrence Durgin Professor of Literature and Chairman of the Department of English at Tougaloo College. He compiled and edited Trouble the Water: 250 Years of African American Poetry (Mentor 1997) and is a co-founder of the Richard Wright Circle.

Bibliography of Works by Richard Wright

Fiction

Uncle Tom’s Children. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1938; HarperCollins, 1993.

Native Son. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1940; HarperCollins, 1993.

The Outsider. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1953; HarperCollins, 1993.

Savage Holiday. New York: Avon Books, 1954; Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1994.

The Long Dream. New York: Doubleday, 1958; Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2000.

Eight Men. Cleveland: World, 1961; New York: HarperPerennial, 1996.

Lawd Today! New York: Avon Books, 1963; Boston: Northeastern UP, 1993.

Rite of Passage. New York: HarperCollins, 1994

This Other World: Haiku. New York: Arcade, 1998. [poetry]

Non-fiction

12 Million Black Voices. New York: Viking, 1941

Black Boy. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1945; HarperCollins, 1993.

Black Power. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1954; New York: HarperPerennial, 1995.

The Color Curtain. Cleveland: World, 1954; Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1994.

Pagan Spain. New York: Harper & Row, 1957; New York: HarperPerennial, 1995.

White Man, Listen! New York: Doubleday, 1957; New York: HarperPerennial, 1995.

American Hunger. New York: Harper & Row, 1977.

Selected Bibliography of Works About Richard Wright

Fabre, Michel. The Unfinished Quest of Richard Wright. 1973; Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

Fabre, Michel. The World of Richard Wright. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1990.

Gayle, Addison. Richard Wright: Ordeal of a Native Son. New York: Doubleday, 1990.

Kinnamon, Keneth. The Emergence of Richard Wright. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1973.

Miller, Eugene E. Voice of a Native Son: The Poetics of Richard Wright. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1990.

Rampersad, Arnold, ed. Richard Wright: A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1995.

Rowley, Hazel. Richard Wright: The Life and Times. New York: Henry Holt, 2001.

Walker, Margaret. Richard Wright: Daemonic Genius. New York: Amistad, 1988.