Mississippi’s Civil War chronicle includes such notable generals as Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, Joseph E. Johnston, and John C. Pemberton, as well as the thousands of common men they commanded. Surprisingly, an untold number of daring women joined them on battlefields across the state, even though societal standards of the time forbade them to do so.

When the Civil War broke out, men were the ones, obligated by a sense of duty and honor, to march away and fight for their respective causes. However, wives, sisters, mothers, and daughters from both the North and South disguised themselves as men and took up arms to fight. And like their male counterparts, women soldiers suffered the same hardships while stationed in faraway locations that often had completely different climates and environments than those they left behind.

These women were motivated by multiple reasons to risk not only their lives on a battlefield, but also the public humiliation and shame that would accompany the discovery of their true identities. Perhaps the most prominent factor was a desire to avoid being separated from loved ones who had marched off to war, but others joined the army to escape abusive family members. Like many of their male counterparts, patriotism and a desire for adventure prompted other women to join the ranks. Still others were inspired by the opportunity to improve their legal, economic, and social status. Victorian women did not enjoy many legal rights or social opportunities, and by assuming a male identity, they were able to obtain freedoms previously denied them due to their gender. For example, in male disguise, they could purchase land, take advantage of more abundant and better paying jobs, and even vote.

Once these bold women decided to enlist, they faced several daunting tasks in order to become soldiers. One was assuming a convincing disguise that would allow them to blend in to the male-dominated military. Then they had to negotiate the enlistment process, which included submitting to a medical examination. In some instances, surgeons merely checked for working body parts recruits needed to march and shoot a gun. Thus, fortunate women were able to pass such cursory medical examinations and slip quietly into the ranks.

Not only was it relatively simple for female recruits to fool an examining surgeon, but it was also not terribly difficult to deceive the male soldiers with whom they served. Prior to identification cards that we use today, it was rather simple to adopt a new persona. Women merely assumed a male alias, cut their hair short, and donned male clothing. Furthermore, war was the domain of men so few people, if any, thought women would even attempt to enlist in the military since they were not supposed to perform men’s duties or wear men’s uniforms, which were often ill-fitting and baggy, thereby hiding the feminine figure. Clothing defined gender in Victorian society. Beyond the social rules that controlled women’s dress, the law actually forbid women from wearing pants. Therefore, male soldiers often overlooked women in uniform simply because they were unaccustomed to seeing them don trousers.

The background of female soldiers also played a role in their ability to serve undetected. A majority of these women came from working class or farming backgrounds and were already accustomed to the tasks required of soldiers, such as shooting, riding horses, or performing manual labor. Yet another factor that enabled women soldiers to blend in was the fact that there were large numbers of young boys who served in both armies. The presence of youthful lads who often lacked facial hair and had higher-pitched voices led men to easily mistake a female soldier for a pre-pubescent boy.

Because women served disguised as men, researchers will never be able to pinpoint exactly how many served as soldiers during the Civil War. Estimates range anywhere from the hundreds to the thousands. When considering nearly three million men fought, it is obvious that women comprised an insignificant number of the fighting force. Yet, they suffered and gave their lives like their male comrades for the same causes. They performed the same duties and fought in every major campaign of the war, including engagements in Mississippi.

From the beginning, military officials from both sides deemed major resources in the Magnolia State — such as the Mississippi River and network of railroads — vital to the war effort. The desire to control these resources led armies to clash in bloody battle and standing in the front lines of these battles were women in disguise.

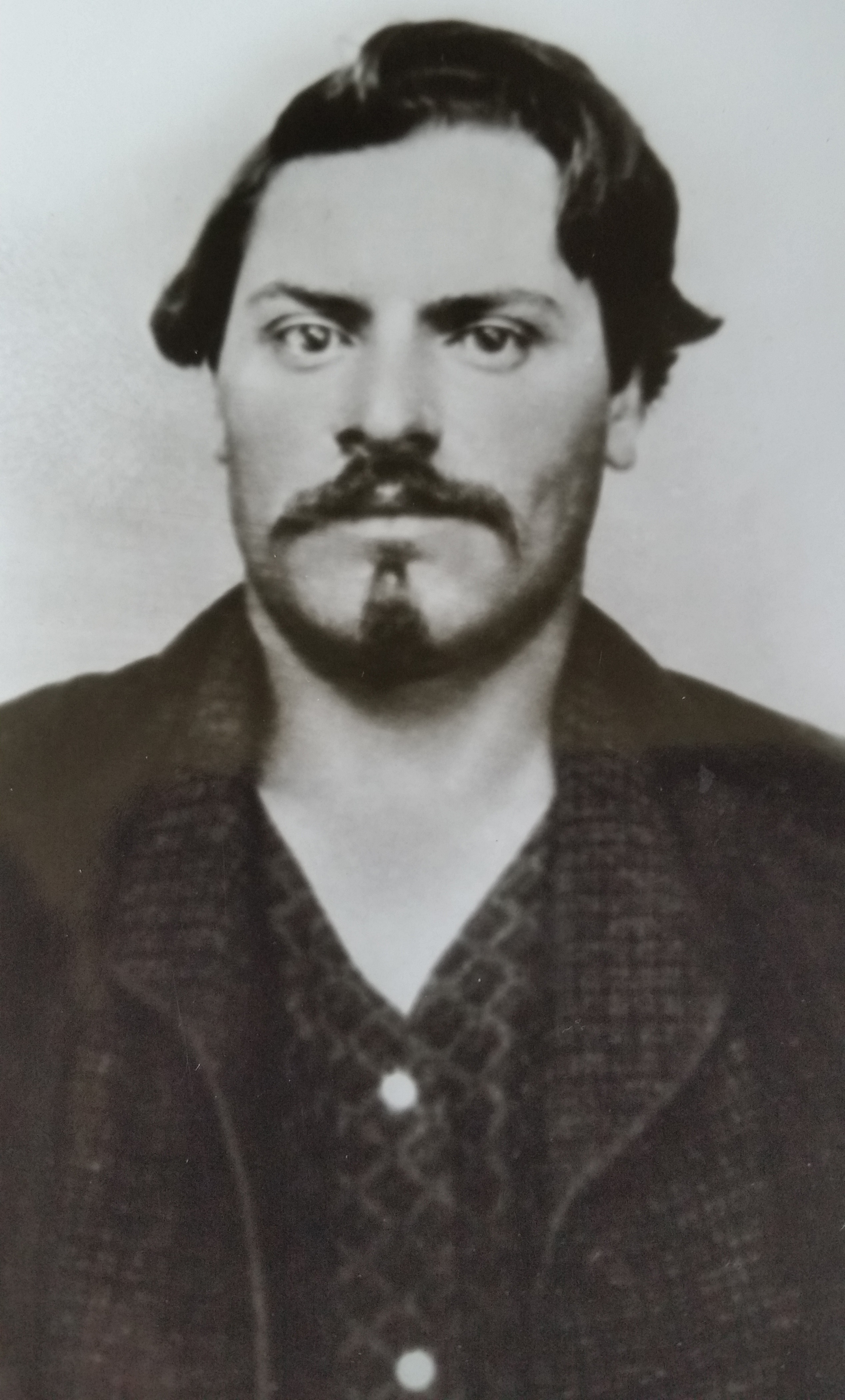

Almeda Hart, one of the notable women who served in Mississippi, followed her husband Henry to war when he enlisted in the 127th Illinois Infantry. Disguised as “James Strong,” she served as a courier during the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou. Fought December 26-29, 1862, it was the first major attempt by the Federals to capture Vicksburg, the last Confederate stronghold along the Mississippi River. Prior to the engagement, she wrote a letter to her mother reassuring her that she was armed with “2 good braces of pistols and a good sabre” and could take care of herself as she rode across the battlefield carrying messages.

Joining Almeda Hart in the Federal army during this engagement was a German woman known only by her male alias, “Charles Junghaus,” who enlisted in the 3rd Missouri Infantry. She was not the only woman to serve in a Missouri unit in Mississippi. Deeply divided, the “Show Me” state sent Federal and Confederate units into service during the Civil War. Therefore, it is not surprising that regiments from Missouri found themselves opposing each other, as was the case in Vicksburg. On the Federal side was Junghaus with the 3rd Missouri. In the Confederate service was at least one woman with Brigadier General Francis Cockrell’s Missouri brigade. Described as “tan, dirty, [and] freckled,” this unknown woman fought in multiple battles in Mississippi.

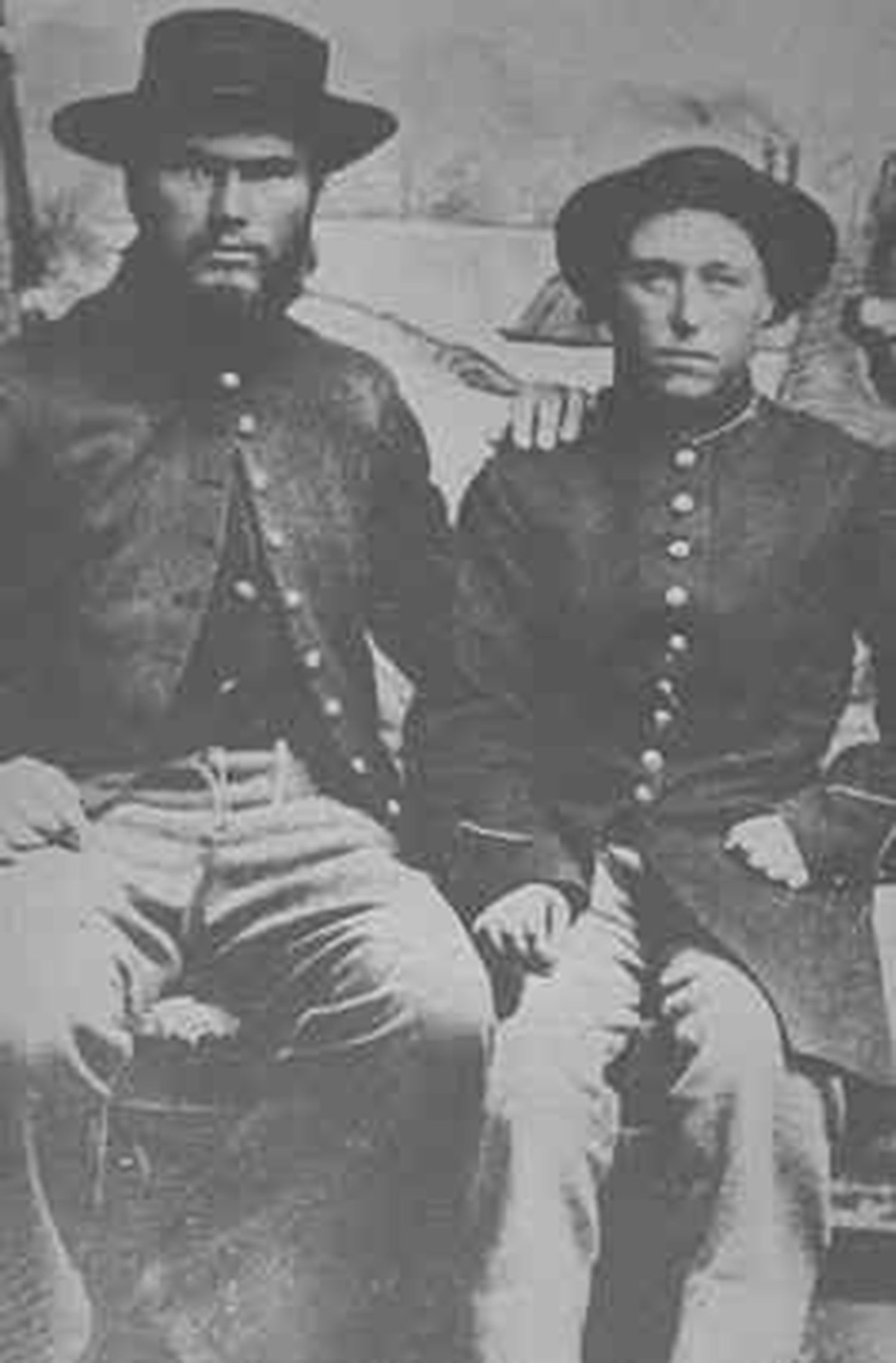

Another female soldier in Mississippi was Irish immigrant Jennie Hodgers. She enlisted as “Albert Cashier” in the 95th Illinois Infantry. With her regiment, she saw action during Grant’s Mississippi Central Railroad Campaign in late 1862. Then, at Vicksburg six months later, Confederates captured Hodgers while she was on a reconnaissance mission. The feisty woman managed to escape by grabbing her captor’s rifle and knocking him down with it. She further displayed her spirited nature when she defiantly stood upon the works at Vicksburg and taunted the Confederates. Today, visitors at Vicksburg National Military Park can find Jennie Hodgers’s alias inscribed inside the Illinois monument. Misspelled as “Albert D.J. Cashire,” it appears on the tablet for Co. G of the 95th Illinois Infantry.

After the fall of Vicksburg, Hodgers and her regiment occupied Natchez until October 1863, after which they headed to Louisiana to participate in the ill-fated Red River Campaign which concluded in May 1864. Following the Union failure there, Pvt. Cashier and her male comrades engaged in another disastrous venture that culminated in the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads in Mississippi where feared Confederate cavalry leader Nathan Bedford Forrest routed Federal forces in June 1864. The diminutive Irishwoman managed to survive not only the fateful battle but also the war.

As for women soldiers from Mississippi, research reveals several who served. But because those who recorded their accounts did not identify them, their names have been lost to history. One such soldier was a runaway enslaved girl from Natchez who served for a few weeks as “William Bradley.” A light-skinned Black girl, she passed as a white man in Miles’ Legion, a Confederate unit. Her service came to an abrupt end, however, when her master recognized her while she was marching up Main Street in Natchez with her company in April 1862.

Two years later in July 1864, Brigadier General Winfield Scott Featherston led his brigade of all Mississippi units in an ill-fated charge during the Battle of Peach Tree Creek in Georgia. Two of the Mississippians who were injured and captured during the engagement turned out to be women. One of them had been shot in the ankle, resulting in a Federal surgeon amputating her foot. The other had been shot in the chest and thigh. Unfortunately, no further information is known about her, but with such grievous wounds, she likely did not return home to Mississippi.

Like their names, the heroic deeds of women soldiers have largely been forgotten by history, yet they served as inspirations to influential people such as Mississippi author William Faulkner, who included a woman soldier in his work. Drusilla Sartoris, a character in his 1938 novel, The Unvanquished, disguised herself as a man and fought with her uncle’s cavalry regiment in order to avenge the deaths of her fiancé and father.

The legacy of female fighters in the Civil War still endures. Their accomplishments helped pave the way for current women soldiers to serve in all combat roles, a right the government granted them in 2015, over 150 years after females were already fighting and dying on Civil War battlefields. Among those were women from Mississippi and their sister soldiers from other areas who fought in battles in the Magnolia State. These female fighters bring to light a new understanding of Mississippi’s Civil War history.

Shelby Harriel is an instructor of mathematics at Pearl River Community College. This article was adapted from her book, Behind the Rifle Women Soldiers in Civil War Mississippi, which was published in 2019 by University Press of Mississippi.

Lesson Plan

-

Almeda Butler Hart, alias “James Strong,” who served as Brigadier General David Stuart’s mounted courier during the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou. She followed her husband, Henry, to war in the 127th Illinois Infantry. She was about twenty-five years old at the time of the battle. This is a younger photo of her. Private collection of the Halstead family, Pecatonica, Illinois. -

Henry Hart, Almeda’s husband, Co. F, 127th Illinois Infantry. He served as a blacksmith for Brigadier General David Stuart. Private collection of the Halstead family, Pecatonica, Illinois.

-

Jennie Hodgers enlisted in the 95th Illinois Infantry as Albert D.J. Cashier and was assigned to Company G. She served for the duration of the war with the 95th Illinois, which fought approximately 40 battles, including the Siege of Vicksburg. -

Jennie Hodgers, alias “Albert D.J. Cashier,” Co. G, 95th Illinois Infantry with an unknown pard. Vicksburg National Military Park.

Sources

Harriel, Shelby. Behind the Rifle: Women Soldiers in Civil War Mississippi. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2019.