Great football players are accustomed to receiving golden trophies and flashy headlines. Football and ballads, however, make for a rare combination. Nevertheless, in 1969, Lamont Wilson, a postman from Magnolia, Mississippi, literally began singing the praises of his favorite player, Ole Miss Rebels’ star quarterback, Archie Manning. Wilson was inspired to write the ballad honoring Manning following the Rebels’ 38-0 demolition of the Tennessee Volunteers during that year’s football season.

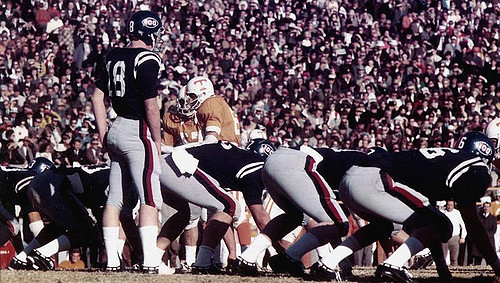

For Rebel fans, the 1969 victory against Tennessee represented revenge for Ole Miss’s loss to the Volunteers during the previous season. In a preseason interview with reporters, Tennessee linebacker Steve Kiner bluntly stated that he was unimpressed with Manning and the rest of the Ole Miss team. Although sports reporters and media outlets described Ole Miss as having “all the horses” among the athletes on its team, Kiner declared that he saw only “mules.” To make matters worse, Tennessee fans in attendance at the highly anticipated rematch in Jackson wore “Archie Who?” buttons. The taunting message was a response to faithful Rebels’ fans who regularly wore “Archie” buttons to each game. In his ballad, Wilson mocked “Hee-Haw Kiner” and Volunteer fans for what he regarded as misplaced arrogance.

Set to the tune of Johnny Cash’s “Folsom Prison Blues,” Wilson’s “The Ballad of Archie Who” referred to Manning as the “real stud hoss” and “the best dad-burned quarterback to ever play the game.” Country singer Murray Kellum and his “Rebel Rousers” band recorded Wilson’s ballad at Malaco Records in Jackson. Upon its release, “The Ballad of Archie Who” became a hit across the state and essentially enshrined Manning as a Mississippi folk hero, especially to White Mississippians. (Given that Ole Miss, Mississippi State, and Southern Mississippi had no Black players until the early 1970s, African Americans throughout the state remained loyal to and mostly concerned with gridiron happenings at Alcorn State, Jackson State, and Mississippi Valley State.) University of Mississippi historian David Sansing best describes what Manning represents to many Mississippians as well as the significance of Wilson’s tune by the following: “He’s not a celebrity. He’s a folk hero. The difference is they write songs about celebrities, but they write ballads about folk heroes.”

Few Mississippi athletes have been more revered than Archie Manning. “The Ballad of Archie Who” immortalized Manning through music, but at the same time, water towers in the state were also emblazoned with Manning’s name, and national magazines identified Manning as one of college football’s best players and praised his personal character. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, a time when many Americans viewed Mississippi as the nation’s bastion of racism, violence, and poverty, Manning’s rising football career provided the state with a symbol of success and pride. One Mississippian remarked, “when outsiders pointed to James Meredith, the Philadelphia murders, the Ku Klux Klan—everything that was wrong with the Deep South in the 1960s—there was always an answer: Yeah, but we’ve got Archie Manning, a straw to grasp.” Mississippi sportswriter Rick Cleveland contends that Manning emerged into the national spotlight when “everybody was taking pot shots at Mississippi.” Through the quarterback’s performance on the field and his humble demeanor, Cleveland also notes that Manning gave the state “something to brag about.” State politicians and journalists also commended Manning’s performance both on and off of the field. Through speeches, letters, and even entries into the Congressional Record, Manning was regarded as the ideal youth and an All-American, patriotic, humble role model who embodied positive values during a time of immense change and conflict for the state and the nation. In the tumultuous 1960s, when Mississippi and Mississippians needed something optimistic, Archie Manning emerged as a cultural icon at just the right time.

Manning was born and raised in Drew, a small town located in Sunflower County in the Mississippi Delta. Elisha, his father, was a World War II veteran who managed the Drew Supply Company. His mother, Jane “Sis” Manning, worked as a secretary for a local attorney. The young redhead experienced a busy childhood full of church activities, school, and numerous sports. He starred for Drew High School in football, basketball, and baseball, and was named valedictorian of his 1967 graduating class. Manning’s teenage years coincided with the rise of a vibrant African-American freedom struggle in Mississippi, particularly in Sunflower County. Voter registration efforts during 1964’s Freedom Summer, as well as the desegregation of Drew public schools in 1965, disrupted the segregationist order that had existed in the state since the latter part of the nineteenth century.

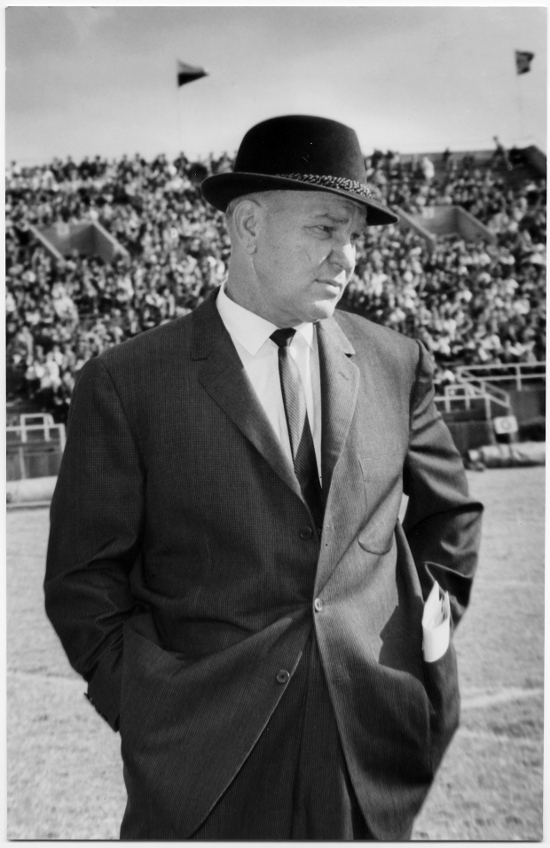

In the summer of 1967, Manning arrived at the University of Mississippi to play football and baseball. Although he earned his fame on the gridiron, Manning was also a stellar performer on the baseball diamond. His play at shortstop caught the eyes of professional scouts, and he was even drafted by major league baseball teams on several occasions. He found his future, however, as a quarterback under the tutelage of college coaching great John Vaught. Over the course of his previous twenty-one years at Ole Miss, Vaught had established a football powerhouse at the University of Mississippi. He had guided the Rebels to six Southeastern Conference championships, four Sugar Bowl victories, and three national championships in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Due to several mediocre seasons in the late 1960s, however, Ole Miss’s dominant days in football appeared to be over.

Manning’s arrival, then, provided just the right spark to the Ole Miss program. Following his freshman year of play on the junior varsity squad, the sophomore Manning led the Rebels to a 7-3-1 record in 1968, a season that included a Liberty Bowl win in Memphis over Virginia Tech. Manning faced great personal tragedy when his father committed suicide during the summer prior to his junior year. His father’s death caused Manning to consider quitting school and returning home to work, but his family encouraged him to complete his education and to continue playing sports. With his family’s blessing, Manning returned to Oxford in the fall for his junior year.

Manning’s 1969 season was outstanding, featuring the aforementioned blowout win over Tennessee and a record-setting performance against coach Bear Bryant’s Alabama Crimson Tide, the latter of which was aired by the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) and was the first nationally televised primetime college football game. As a junior, Manning threw for 1,762 yards, ran for 502 yards, and had 23 total touchdowns. His stellar play as a junior made him a finalist for the 1969 Heisman Trophy, arguably the most prestigious individual honor in college athletics, and earned Manning numerous other honors, including the Southeastern Conference Player of the Year, the Walter Camp Award for the outstanding back in college football, and a spot on the All-American Team. On January 1, 1970, Manning topped off his junior year by helping Ole Miss win the Sugar Bowl against Arkansas, 27-22. He was subsequently named the game’s Most Valuable Player.

Due to their strong finish during the 1969 season and Manning’s return the following year as a senior, the Rebels entered the 1970 season as one of the national favorites in college football. Manning and his crew proved the preseason experts correct by winning their first four games, one of which was an easy 48-23 victory over Alabama. A surprise loss to in-state rival Southern Mississippi, however, sent Ole Miss into a late-season tailspin. Stung by two more losses and a broken left arm suffered by Manning during a game against Houston, the Rebels did not live up to the lofty preseason expectations. Manning delivered a courageous performance in his final college game, a Gator Bowl loss to Auburn. Playing in spite of the broken arm, Manning helped keep the game’s score close, but the Rebels eventually fell short, 35-28. Although Manning also failed to win the 1970 Heisman Trophy and finished his collegiate career on a seemingly down note, he ended his time at Ole Miss with a litany of school and conference records.

Following the 1970 football season, approximately 10,000 people gathered in Drew on February 21, 1971, for “Archie Manning Day.” A host of statewide political leaders and dignitaries honored Manning for his football accomplishments, as well as his humility and representation of the state in a positive manner. In his address to the audience, Senator James O. Eastland, from nearby Doddsville, Mississippi, claimed that Manning “has done more good for the state on the national scene than any man of the generation.” The hometown football hero then spoke to the crowd, received numerous accolades and gifts, and bid farewell to the state before heading down to New Orleans to begin his professional football career.

Manning played fourteen seasons in the National Football League (NFL), most of which were with the perennially hapless New Orleans Saints. From 1971 to 1981, Manning served as quarterback for one of the NFL’s weakest franchises and sustained numerous injuries. In 1978, Manning accomplished a remarkable feat when he was named as the National Football Conference (NFC) Player of the Year despite his team’s losing record. He finished his football playing career in 1985 after serving short stints as quarterback for the Houston Oilers and the Minnesota Vikings. Despite his toughness and individual talent, Manning never competed in the NFL playoffs. Manning continues to be a popular figure in New Orleans, a testament to his loyalty to the city and the Saints franchise during all those losing years. Currently in his late sixties, he and his wife, Olivia, continue to reside in the Crescent City.

Manning remains in the spotlight due largely to the success of his sons, Peyton and Eli, both Super Bowl champion quarterbacks in the 2000s and 2010s. He continues to play a public role himself in sports broadcasting and as a commercial spokesman in Mississippi and Louisiana. His popularity has remained strong over the past several decades. In 1992, he was named Mississippi’s Most Popular Athlete of the Century, and in a 1999 Jackson Clarion-Ledger poll, Mississippians voted overwhelmingly for Manning as Mississippi’s Athlete of the Century. He received nearly three times the number of votes as the second-place finisher, Pro Football Hall of Fame running back, Walter Payton. Nearly fifty years after “Archie Fever” swept through Mississippi, the lanky, red-headed boy from Drew remains one of the state’s most renowned figures.

Charles Westmoreland, Jr. is an associate professor of history at Delta State University.

Other Mississippi History Now articles:

Lesson Plan

-

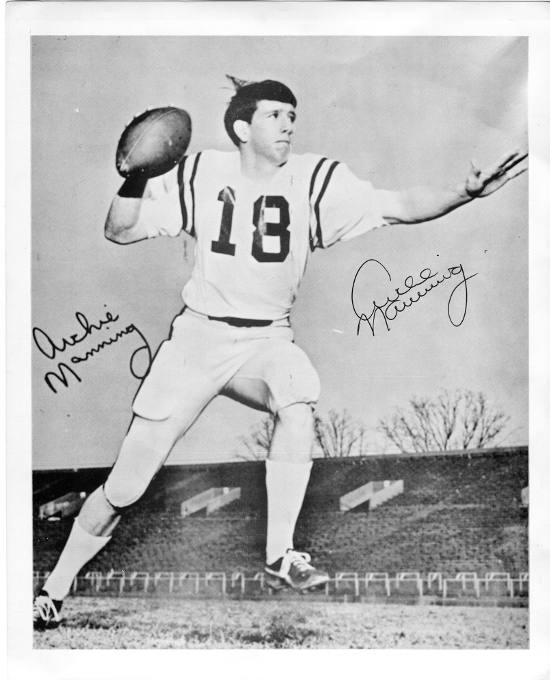

Autographed picture of Archie Manning. Photograph courtesy of the Department of Archives and Special Collections, University of Mississippi Libraries, J.D. Williams Library, John Leslie Collection (MUM01795). Reference URL "http://clio.lib.olemiss.edu/ cdm/ref/collection/leslie/ id/73":http://clio.lib.olemiss.edu/cdm/ref/collection/leslie/id/7 -

Photograph of quarterback Archie Manning during the 1969 game between the Ole Miss Rebels and the Tennessee Volunteers. Photograph by RebelNation 1947 licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license (CC BY-SA 2.0). Reference URL "https://commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/File:Ole_Miss_vs_Tennessee_1969_ (4233310964).jpg.":https://goo.gl/kQ3FyH

-

Photograph of University of Mississippi head football coach John Vaught. Photograph courtesy of the Department of Archives and Special Collections, University of Mississippi Libraries, J.D. Williams Library, Ed Meek and Meek School of Journalism and New Media Collection (MUM00739). Reference URL "http://clio.lib.olemiss.edu/ cdm/ref/ collection/meek/ id/3316.":http://clio.lib.olemiss.edu/cdm/ref/collection/meek/id/3316 -

Photograph of New Orleans Saints quarterback Archie Manning attempting a pass during a November 2, 1980 away game against the Los Angeles Rams. “1986 Jeno’s Pizza - #25 Archie Manning.” Jeno’s. 1986. (Photograph was taken from the 1980 NFL season and re-published in 1986 for the Jeno’s Pizza football card set.) Reference URL "https://commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/File: 1986_Jeno%27s_Pizza_-_25_- _Archie_Manning.jpg.":https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1986_Jeno%27s_Pizza_-_25_-_Archie_Manning.jpg -

Photograph of Archie Manning and Peyton Manning speaking at an event in Phoenix, Arizona. Photograph by Gage Skidmore licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license (CC BY-SA 3.0). Reference URL "https://commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/File:Archie_Manning _%26_Peyton_Manning_ by_Gage_Skidmore.jpg.":https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Archie_Manning_%26_Peyton_Manning_by_Gage_Skidmore.jpg

Sources and suggested readings:

Lars Anderson. The Mannings: The Fall and Rise of a Football Family. New York: Ballantine Books, 2016.

Constance Curry. Silver Rights. Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 1995.

Archie Manning and Peyton Manning. Manning: A Father, His Sons, and a Football Legacy. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2000.

William W. Sorrels and Charles Cavagnaro. Ole Miss Rebels: Mississippi Football. Huntsville, AL: Strode Publishers, 1976.

John Vaught. Rebel Coach: My Football Family. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1971.