The 1830s witnessed a succession of profound, and often wrenching, changes that remade Mississippi. At the start of the decade, White settlement was confined to the region between the Mississippi and Pearl Rivers and to another small pocket on the upper branches of the Tombigbee River. Despite the ratification of the Treaty of Doaks Stand (1820), most of the state remained in the hands of the Choctaws and Chickasaws. By 1840, these Native nations had been deported west of the Mississippi River, and the state had emerged as the nation’s leading cotton producer, forging a political culture that epitomized the Age of Jackson.

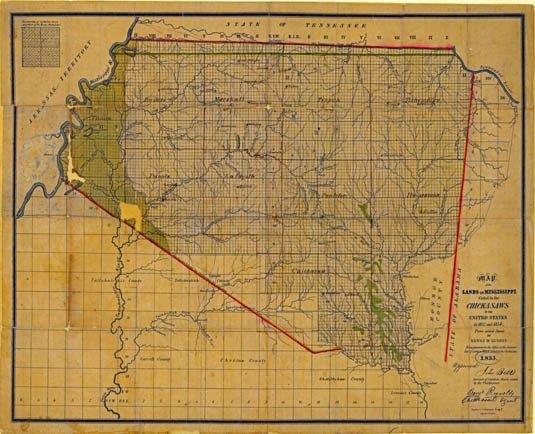

Since the 1790s, the federal government had cast covetous eyes on Native lands in the southeast. Through a combination of assimilationist programs, debts accrued at federal trading houses, treaties, and warfare, the United States had gained control of loose pieces of Native land, but many nations—including the Choctaw and Chickasaw—remained entrenched on their lands. The election of Andrew Jackson in 1828 unleashed a renewed assault on the southeastern Native Americans. The passage of the Indian Removal Act (1830) allowed the national government to purchase the Native lands in the state and to forcibly relocate Native Americans to federal lands west of the Mississippi River. The state of Mississippi conspired with the federal government to place additional pressure on the Native nations. In 1829 and 1830, the legislature passed two State Law Extension Acts, which extended state laws over Choctaw territory, made it illegal for chiefs to exercise political authority, and abolished all Choctaw customs not recognized by the state of Mississippi. With the signing of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek (1830), the Choctaw became the first nation to be expelled from their homeland and forced to resettle in the Indian Territory. In 1832, the Chickasaw and the United States completed the Treaty of Pontotoc Creek, through which the Chickasaw were forced to cede their lands in northern Mississippi and be deported from the state.

The deportation of the Choctaws and Chickasaws opened some of the nation’s most fertile farmland to cultivation at a time when soaring cotton prices and a general loosening of the credit markets promised quick profits to enterprising planters and slave traders looking to make their fortunes in the Southwest. Between 1833 and 1837, Mississippi’s five land offices sold some seven million acres of public lands, much of it on easy credit. Virginia attorney and humorist Joseph Glover Baldwin captured the heady, feverish enthusiasm of the times in his semi-autobiographical, The Flush Times of Alabama and Mississippi. Baldwin recalled, “The country was just settling up. Marvelous accounts had gone forth of the fertility of its virgin lands; and the products of the soil were commanding a price remunerating to slave labor as it had never been remunerated before.” Growing demand for cotton in England’s textile mills drove this economic dynamo, but its gears and pistons were lubricated by the cheap credit that emanated from English banks and that made its way to cotton factors in port cities like Mobile and New Orleans. Hoping to reap their share of the windfall, banks in the southwestern states began issuing notes with reckless abandon. “Money, or what passed for money, was the only cheap thing to be had,” Baldwin noted ruefully. “The State banks were issuing their bills by the sheet, like a patent steam printing-press its issues;” he continued, “and no other showing was asked of the applicant for the loan than an authentication of his great distress for money.”

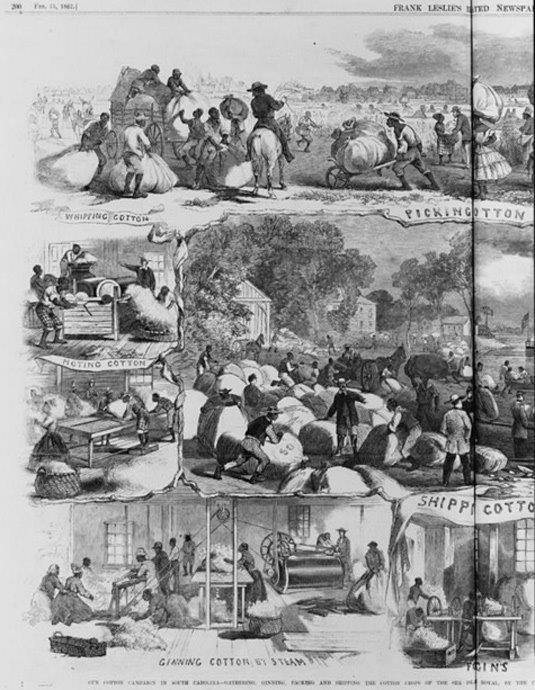

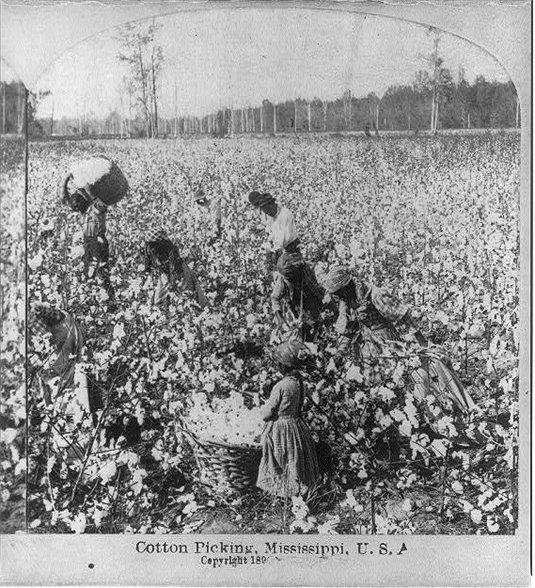

Between 1820 and 1833, Mississippi’s cotton production soared from approximately 20 million to 70 million pounds. By 1839, the opening of the Choctaw and Chickasaw lands had catapulted that figure to some 193.2 million pounds, making the state the nation’s largest producer of cotton. Mississippi relinquished that title during the 1840s, but by the eve of the Civil War, the state’s farms and plantations yielded over 535 million pounds of cotton, the most in the United States. The labor of enslaved Africans and African Americans made the dramatic growth in cotton production possible. During the 1830s, Mississippi’s enslaved population increased by nearly 200 percent, exploding from 65,659 to 195,211. The increase was even more dramatic in some counties. For example, the number of enslaved people in Lowndes County leapt from 1,066 to 8,771, while the enslaved population of Noxubee County—which had been carved out of the Choctaw cession—stood at 7,157 by the end of the decade.

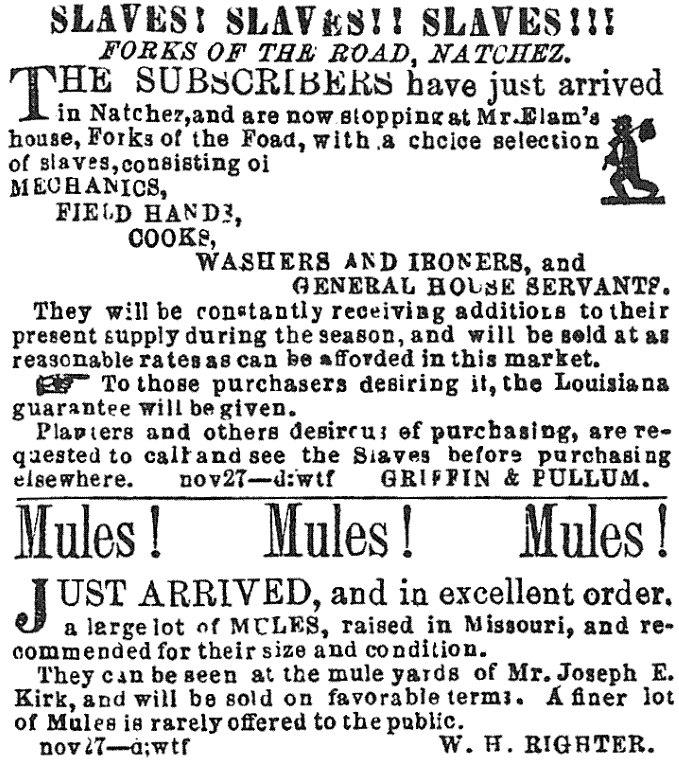

The vast majority of these enslaved men and women came from Maryland and Virginia, where decades of tobacco cultivation and sluggish markets were eroding the economic foundations of slavery, and from older seaboard slave states like North Carolina and Georgia. These enslaved people were shipped along the coast to markets in New Orleans and Natchez or were marched overland. Others came down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers carried by planters and speculators who were hoping to take advantage of the booming market in cotton and enslaved people. Although precise figures are unavailable, one early historian of slavery in Mississippi estimated that over 100,000 enslaved people were brought into the state by traders during the 1830s. Advertisements posted by slaveowners and county jailors offer a glimpse of the destruction wrought by the domestic slave trade. In February 1836, for example, the Vicksburg Register announced the arrest of Aleck, a young man of thirteen or fourteen years, who had been carried to a plantation in Warren County by Wesley Newberry, a trader from Georgia. That same month, The Mississippian [Jackson, Miss.] carried an advertisement for a man named Cheesman. Before his capture, this twenty-nine-year old bondsman had been purchased by one John Avery, a “speculator in Negroes,” from the neighborhood of Giles County, Tennessee.

In 1836, President Andrew Jackson applied a strong, and ultimately destructive, corrective to the speculative mania that had raged in the Southwest. Terrified of the “frauds, speculations, and monopolies” that had come to characterize land sales, Jackson issued the Specie Circular, which declared that public lands must be purchased with hard currency. At the same time, the directors of the Bank of England were growing increasingly suspicious of the poorly capitalized and unregulated rural banks and cotton merchants that were the lynchpins of the Atlantic cotton trade. When the Bank of England hiked its interest rates, American lenders followed suit, and rates soared to 37 percent in the late summer and fall. Banks on both sides of the Atlantic collapsed and dragged down English textile manufacturers, who could no longer afford to purchase American cotton. The Panic of 1837 had begun, and with it the Flush Times of the 1830s came to a calamitous end.

Surveying the wreckage of the panic, Natchez barber, businessman, and aspiring free Black planter William Johnson—himself the child of an enslaved woman—wrote, “Times are Gloomy and sad to day. Money is no money . . . I know not what will become of us . . . terrible times.” A Virginian residing in Kemper County offered a bleak assessment of planters’ prospects after the collapse. The combination of “over-trading in every respect” and the “operation of the government in deranging the whole currency of the country” had plunged Mississippi into ruin. “Negroes have fallen considerably,” he wrote, adding that “the system of selling them on a credit [had] advanced their value so enormously.”

The expulsion of Native Americans and influx of White settlers with enslaved people brought about a revolution in the state’s political culture. By 1831, it was clear that the Constitution of 1817 could no longer accommodate the state’s growing population, nor did it reflect the impending shift of political power north to the Choctaw and Chickasaw cessions. The Constitution of 1832 was, in many ways, the embodiment of Jacksonian Democracy. It eliminated property requirements for voters and elected officials, and it declared that all judges and almost all county and state officials would be chosen by popular election. The Natchez aristocracy, which had controlled Mississippi politics since the territorial days, regarded the new document with dread. One former Supreme Court justice scoffed, “Our constitution is the subject of ridicule in all the States where it is known. It is referred to as a full definition of mobocracy.” The expansion of the franchise gave birth to a vibrant, if somewhat raucous, political culture. Looking back on his childhood in antebellum Kemper County, Eb Felton remembered what happened when men gathered at courthouses and at the polls. “It was a great time,” he recalled. While the judges and attorneys attended to legal matters and politicians harangued for votes, “all the rest got out and swapped horses and got drunk and fought.” While the political process became more open, politics also became more focused. During the 1830s, Mississippi’s elected officials began constructing a full-throated defense of slavery that would become a mainstay throughout the remainder of the antebellum decades.

Max Grivno is an associate professor of history at the University of Southern Mississippi.

Other Mississippi History NOW articles:

Chickasaws: The Unconquerable People

Cotton in a Global Economy: Mississippi

The Forks of the Road Slave Market at Natchez

Free People of Color in Colonial Natchez

Mushulatubbee and Choctaw Removal: Chiefs Confront a Changing World

-

Map of the lands in Mississippi ceded by Chickasaws in 1832 and 1834. Courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, File 8152-1-map. -

Advertisement for slave sales at the Forks of the Road from the Natchez Daily Courier, November 27, 1858. (The “Louisiana Guarantee” refers to that state’s more generous buyer-protection laws concerning the slave trade.) Below, similar advertisement for mules. Courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

-

A drawing from the February 15, 1862, edition of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, depicts the “picking, ginning, and shipping” of cotton. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-116585. -

Cotton pickers in Mississippi, mid-1800s. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-49307.

Sources and suggested readings

Baptist, Edward E. The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. New York: Basic Books, 2014.

Johnson, Walter. River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2014.

Moore, John Hebron. The Emergence of the Cotton Kingdom in the Old Southwest: Mississippi, 1770-1860. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1988.

Rothman, Adam. Slave Country: American Expansion and the Origins of the Deep South. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2005.

Rothman, Joshua D. Flush Times and Fever Dreams: A Story of Capitalism and Slavery in the Age of Jackson. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012.