In 1949, political scientist V. O. Key suggested that “insofar as any geographical division remains within the politics of [Mississippi] it falls along the line that separates the delta and the hills.” By the time Key thus defined the state’s political line of demarcation, James O. Eastland had already been a significant player on both sides of it.

James O. Eastland, elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives in 1927, quickly rose to prominence as a floor leader for the darling of the state’s poor white farmers, Theodore G. Bilbo, who was then serving his second stint as governor. After a single term in the legislature, Eastland returned to private life until 1941 when he began a U. S. Senate career that would span four decades, during which he would become a champion of his former enemies, the Delta cotton planters. However variable his role in state politics, his national reputation emerged from a consistent and implacable opposition to both domestic civil rights and international Communism, which became, in his worldview, inextricably linked. For Eastland, in the words of one historian, “the fight against Communism was a fight for white supremacy—much of his hatred for Communism grew from his concerns about its potential effect on black Americans.”

Born on a plantation

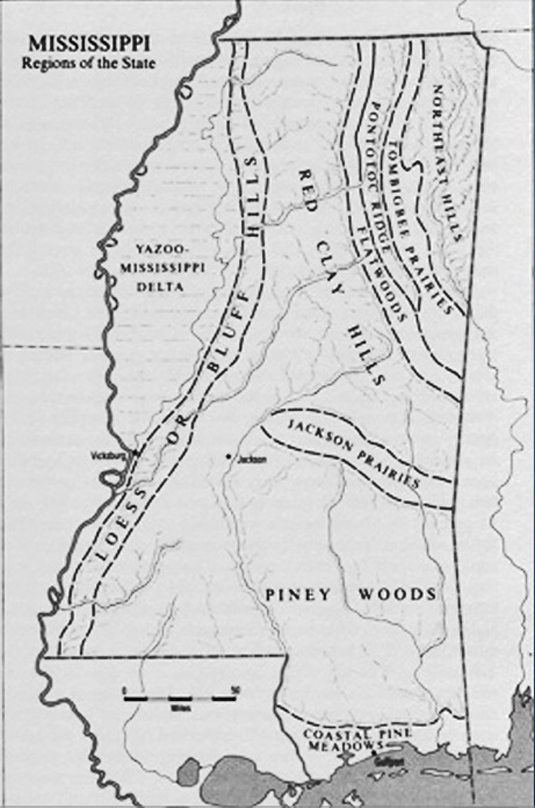

James Oliver Eastland was born in the Delta, a flat region running along the Mississippi River with rich soil suited for large successful cotton farming, but grew up in Scott County in the central region of the state where poor White farmers scratched out a meager existence in poor soil on small farms. There the farmers nursed a festering resentment against the prosperity and political clout of the planters of his native region. (See map of Mississippi regions.)

His great-grandfather, Hiram Eastland, had settled in Scott County, midway between Jackson and Meridian, in the 1830s. An enterprising merchant, this family patriarch bequeathed to his son Oliver a significant estate, which James’s grandfather then enlarged to include more than 2,000 acres of Delta land in Sunflower County. Oliver Eastland had bought the land for speculative purposes, but his son, Woods, James’s father, acquired it and developed it into a flourishing plantation. There, James Eastland was born on November 28, 1904, only months after his father had orchestrated the gruesome lynching of a Black woman and her lover, who was accused of murdering Woods’s twenty-one-year-old brother, James, in whose memory the newborn was named.

Coming of age in “the Hills”

Within a year, Woods Eastland moved his family back to Scott County, where the son absorbed both the political sensibilities of the predominant poor White Mississippians, including Paul B. Johnson Sr., and the future state publishing moguls, brothers T. M. and R. M. Hederman. He developed enduring friendships with Johnson and the Hederman brothers. Woods Eastland was the dominant force in his son’s life, grooming him from the beginning for a career in politics. Somewhat reserved and an only child, Eastland later remarked that “my father completely controlled me.”

After graduating from Forest High School in 1922, Eastland spent three years at the University of Mississippi before transferring first to Vanderbilt University and then to the University of Alabama. Having passed the bar examination during his senior year at Alabama, he never finished college, dropping out, on his father’s advice, to run, successfully, for the Mississippi Legislature from Scott County in 1927. Along with Courtney Pace, who later became his administrative assistant in Washington, D.C., and Kelly Hammond of Marion County, he formed the “Little Three” who led the fight for Governor Bilbo’s legislative program against the administration’s opponents, led by the “Big Four”: Thomas L. Bailey, Joseph George, Laurence Kennedy, and Walter Sillers (who would later become an Eastland friend and political ally). It was a losing battle, and with the Bilbo administration in a shambles, he decided, again on his father’s advice, not to seek re-election.

From politics back to planter

Meanwhile, the family had returned to the plantation in Sunflower County, and in 1932 Eastland met and married Elizabeth Coleman, a high school teacher in nearby Ruleville. After practicing law briefly in Forest, he moved to Doddsville in Sunflower County to help his father run the plantation. Though still politically active, he did not seek public office and seemed content as a small-town lawyer and planter.

When United States Senator Pat Harrison died in June 1941, the choice of a temporary replacement fell to Paul Johnson, who had been elected governor in 1939. Since the appointment would be largely honorific, lasting only until a special election could be held to fill Harrison’s unexpired term, pundits speculated that Johnson would use the opportunity to allow one of his Scott County boyhood mates to add the title United States Senator to his name. The Hedermans apparently deferred to Woods Eastland, who also politely declined but caught his old friend off guard by asking him to appoint his son, thirty-six-year-old James instead. “The boy’ll do it,” he told the surprised governor. To refuse would have been embarrassing, and Johnson thus inadvertently helped launch one of the most remarkable 20th century Senate careers, not only in Mississippi but in the nation.

Eastland chose not to seek the unexpired term, which would end in 1943, and Congressman Wall Doxey won the race with the open backing of Bilbo, who now held Mississippi’s other U. S. Senate seat. When rumors surfaced that Eastland would challenge Doxey for the full term in 1942, Bilbo sought, unsuccessfully, to dissuade him. Despite Bilbo’s continued support for Doxey, Eastland won both the election and the enduring hostility of his senior colleague.

Launch of a Senate career

Now himself a wealthy Delta planter, Eastland had loosened Bilbo’s grip on poor White voters, according to one scholar, by wooing them away from the “left-leaning economic policies that had held sway through much of the 1930s. He did so by fusing anti-Communism, economic conservatism, and white supremacy into a political philosophy that would not only get him elected in 1942 but also characterize his entire career.”

After World War II, as northern Democrats increasingly embraced the principle of racial equality, Eastland, along with other southerners in Congress, frequently found himself at odds with the leadership of his own party, on labor and social welfare issues as well as civil rights legislation. He remained a staunch supporter of anti-Communist foreign policy, urging President Harry Truman to be lenient with postwar Germany as a means to deter Soviet influence in Europe.

After being re-elected without opposition in 1948, he became chairman of the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee in 1953, giving him a forum from which to hound suspected domestic subversives, especially those involved in civil rights activities and the labor movement. His re-election campaign in 1954 coincided with the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education decision which catapulted the issue of segregation into the national limelight. Denouncing the high court mercilessly, he attacked opponent Carroll Gartin as a racial moderate and swept to victory, carrying seventy of the state’s eighty-two counties.

“Mr. Chairman”

In 1956, Eastland became chairman of the powerful Judiciary Committee, through which passed more than half of all legislation in the Senate, including civil rights bills and judicial nominations. His scrupulously fair handling of the judicial nominations earned the grudging respect of even his liberal colleagues and deflected much of their resentment at his ruthless treatment of the civil rights bills, few of which ever saw the light of day. He even boasted to White audiences in Mississippi that he once had special pockets sewn into his trousers so he could carry civil rights bills around with him to make sure no one called them up for consideration in his absence. The Judiciary Committee became the burying ground of civil rights legislation until the Senate leadership devised ways to circumvent his power in the 1960s.

Meanwhile, as a member of the Committee on Agriculture and Forestry, he zealously guarded the interests of southern farmers, especially the planters of his native Delta, who reaped millions of dollars in annual subsidies. His own plantation, which eventually grew to nearly 6,000 acres, consistently received more than $100,000 a year in price supports until Congress capped the payments at $50,000.

Outside the South, Eastland became the cigar-chomping caricature of segregationist intransigence, but Washington insiders called him simply “the Chairman,” and back home he was “Big Jim.” Re-elected three more times, he never faced significant Democratic opposition again until 1978, though Republican Prentiss Walker challenged him in the general election of 1966, as did Republican Gil Carmichael six years later.

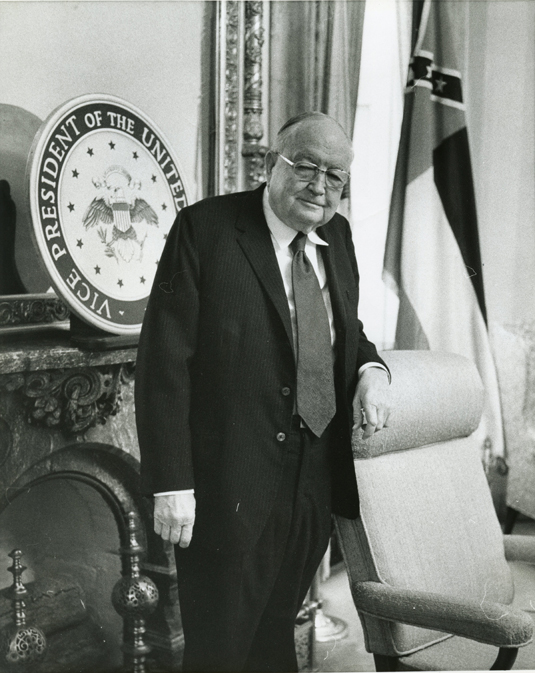

In 1972, Eastland’s seniority and his reputation for fair handling of judicial appointments led his colleagues to choose him as president pro tempore of the Senate, behind only the vice president and the speaker of the house in the line of presidential succession. With House Speaker Carl Albert ill, he twice came within a heartbeat of the oval office when Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned in 1973 and when Vice President Gerald Ford moved up upon the resignation of President Richard Nixon the following year.

By 1978, as a result of the civil rights revolution that he had so fervently resisted, Eastland faced a Mississippi electorate that was almost 30 percent Black. Though he had become reconciled to biracial politics and remarkably earned the endorsement of NAACP leaders Aaron Henry and Charles Evers, he decided to forego the rigors of another campaign. In a final flourish of political sagacity, he resigned on December 27, 1978, several days before his term expired, allowing Mississippi Governor Cliff Finch to appoint his successor, Republican Senator-elect Thad Cochran, to finish the term, thus ensuring Cochran a jump in seniority on his colleagues in the senatorial class of 1978.

Despite his submission to the new realities of racial justice and his increasingly close and apparently genuine friendship with longtime foe Aaron Henry, Eastland never recanted his opposition to civil rights. “I wouldn’t take back anything,” he declared, “I voted my convictions.” In a final twist of irony, following his death in 1986 the board of trustees of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History elected him and murdered civil rights leader Medgar Evers into the Mississippi Hall of Fame on the same day in 1991.

Chester “Bo” Morgan, Ph.D., is history professor and university historian, University of Southern Mississippi.

-

James O. Eastland portrait, circa 1940s. Courtesy James O. Eastland Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Mississippi. -

Mississippi: Regions of the State. The diverse geography of Mississippi had an influence on the state's political development. Map adapted from one in "Atlas of Mississippi" edited by Ralph D. Cross and Robert W. Wales, with Charles T. Traylor, chief cartographer, University Press of Mississippi, and used in "Mississippi: A History" by John Ray Skates.

-

Eastland in Cologne, Germany, during a post-World War II tour of Europe by the Senate Military Affairs Committee, June 1, 1945. Courtesy James O. Eastland Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Mississippi. -

Eastland at White House dinner party with President and Mrs. Lyndon B. Johnson, May 3, 1966. Courtesy James O. Eastland Collection, Archives & Collections, University of Mississippi. -

Eastland presides over a Judiciary Committee hearing, November 1973. Courtesy James O. Eastland Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Mississippi. -

Eastland with Senator John Stennis at the U. S. Naval Air Station in Meridian, Mississippi, April 27, 1973. Courtesy James O. Eastland Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Mississippi. -

Eastland aboard Air Force One with President Richard Nixon, July 31, 1972. Courtesy James O. Eastland Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Mississippi. -

Eastland in the office of the Vice President of the United States, circa 1970s. Eastland, as president ??pro tempore?? of the U. S. Senate, twice came within a heartbeat of the presidency of the United States. Courtesy James O. Eastland Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Mississippi. -

In 1999 the Senate Commission on Art approved the commissioning of a portrait of James Eastland in honor of his longest consecutive service as chairman of the Judiciary Committee and his position as president ??pro tempore??. Portrait by Herbert Elmer Abrams. Courtesy U. S. Senate Collection, Cat. No. 32.00040.000.

Sources:

Asch, Chris Myers. The Senator and the Sharecropper: The Freedom Struggles of James O. Eastland and Fannie Lou Hamer. New York: New Press, 2008.

_____________. “Revisiting Reconstruction: James O. Eastland, the FEPC, and the Struggle to Rebuild Germany, 1945-1946.” Journal of Mississippi History, 67 (Spring 2005): 1-28.

“Biographical Note” in Finding Aid for James O. Eastland Collection. Archives and Special Collections, University of Mississippi Libraries, Oxford, Mississippi.

Chandler, David Leon. The Natural Superiority of Southern Politicians: A Revisionist History. New York: Doubleday, 1977.

Johnston, Earle. Mississippi’s Defiant Years, 1953-1973: An Interpretive Documentary with Personal Experiences. Forest, Mississippi: Lake Harbor Publishers, 1990.

Schlauch, Wolfgang. “Representative William Colmer and Senator James O. Eastland and the Reconstruction of Germany, 1945.” Journal of Mississippi History 34 (August 1972): 193-213.