Every ten years the federal government takes a census; it counts everyone living in the United States and its territories. It has done this since 1790. The census counts everyone — adults, children, citizens, and foreign nationals, and gathers demographic information such as age, education, employment, and the number of family members.

The information collected during a census provides a snapshot of the country. It is a picture of what each state looks like demographically on a typical day in a decennial year. The census count from Mississippi and other states determines for the next decade how people are represented in state and national government, and how federal funds will be allocated to each state. Thus, it is in the best interests of Mississippi that everyone within its boundaries is counted.

Use of the census

The two primary uses of census information are reapportionment of the seats in the U. S. House or Representatives, and redistricting of Mississippi legislative districts. In addition, Mississippi counties use the census information to redraw supervisor districts, municipalities use the census information to redraw voting wards, and school districts use the information for education-improvement grants and projects. This is also the time that the Mississippi Supreme Court considers what impact the population shift in the last decade has had on the circuit, chancery, and county court districts in Mississippi.

While Mississippi is often considered a state of little growth and movement of people, much can happen over a ten-year period. Consider the first decade of the 21st century: It brought Hurricane Katrina migrations; lost manufacturing jobs; new economic growth around Lee County and the Golden Triangle of Columbus, Starkville, and West Point; growth in Hattiesburg and surrounding counties; and the extensive growth of DeSoto County and adjoining areas. Thus, the 2010 census results may cause significant realignment in Senate and House districts in Mississippi. Will coastal representation be diminished due to Katrina migrations? How many seats will be added to Northwest and Northeast Mississippi due to growth in population? Will the loss of population in Southwest Mississippi cause districts there to be enlarged, shifted, or numerically reduced in order to account for and accommodate population shifts throughout the state?

Reapportionment

It is important to distinguish between reapportionment and redistricting. Reapportionment refers to an allocation of congressional seats among the various states; the United States reapportions the available seats in the U. S. House of Representatives after every decennial census. Redistricting refers to the redrawing of boundaries of election districts within a state. It must be done by state legislatures after every census, and is required intermittently as a result of annexations of municipal boundaries, changes in forms of government which require a different number of local government officials, and the like. The problem with reapportionment and redistricting is reflected by the difficulty in measuring population in various districts.

First consider reapportionment. All U. S. House of Representative districts are single-member, and the first matter to be dealt with is the identification of the “ideal” single-member House district. The ideal is defined as the total population divided by the total number of districts.

In federal reapportionment, the solution will be found by asking these questions:

- What is the total population of the United States?

- What is the total number of the House of Representative districts in the United States? Since 1911, the answer has been 435.

- After dividing the total population by the total number of districts, what is the ideal population? Example: In 2000, the U. S. population, according to the census, was 281,424,602. This number, divided by the 435 House districts means that a district with “ideal” population is one that has a population of 646,953.

This may seem simple, but it is a complex procedure. For example, in the reapportionment of the U. S. House of Representatives, we know that of the 435 seats, the U. S. Constitution allows each state to have one representative and two senators. Senate positions are created at large; thus, no reallocation of Senate seats is necessary following a decennial census. Since each state receives one congressional district, the remaining 385 seats (435 minus 50) in the U. S. House of Representatives are allocated among the 50 states based on state population. In this example, the focus of the Congress would be to divide the 385 seats in such a way that all of them would have a population very close to 646,953. Mississippi lost a district after Census 2000, going from five districts to four.

Redistricting

In state districting, the legislative districts in Mississippi are also single-member. (Some states have multi-member state legislative districts, which further compound the population measurement techniques.) In state redistricting, while the number of members in Mississippi’s Senate (52) and House of Representatives (122) do not change, population does. Mississippi’s population in Census 2000 was established at 2,884,666. From this number the legislature searched for the “ideal” Senate district and House district, and then had the difficult task of redrawing districts in order to have each state Senate district and House district reflect the “ideal.” The people who ultimately make the redistricting decisions are the legislators themselves, and a legislator may encounter the risk of losing his or her seat.

Voting Rights Act

Mississippi is one of the states that is governed by Section 5 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, so every redistricting decision made in Mississippi at any level of government must be pre-cleared by the United States Department of Justice before an election can be held. The purpose of Section 5 is to ensure that states with a history of racially discriminatory electoral practices do not implement any change that has the purpose of denying or abridging the right to vote on account of race, color, or language. Section 5 began as a temporary provision of the Voting Rights Act, but the provision has been extended by Congress prior to each expiration date, and has been reauthorized through 2031.

The Justice Department establishes precise directions for the information that must be submitted in order to seek a preclearance for redistricting. Preclearance requires extensive information that the respective entities (counties, municipalities, etc.) must compile prior to submitting the proposal. If all information is not submitted, the preclearance application is rejected out of hand. The attorneys in the Justice Department ask the questions: Does this plan have the purpose of abridging the rights protected by the Voting Rights Act? Does this plan have the effect of abridging rights protected by the Voting Rights Act? If the Justice Department rejects a plan, the submitting jurisdiction can seek a declaratory judgment by filing a lawsuit in the U. S. District Court for the District of Columbia, or it can ask for reconsideration by the Justice Department. Without preclearance, granted either by the Department of Justice or by the district court, the proposed changes are not legally enforceable and cannot be implemented. The jurisdiction must then reconsider and change its plan for redistricting.

Allocation of federal funds

It is not only reapportionment and redistricting that makes census data so important. The related demographic data requested in the decennial census forms predicts and determines the allocation of federal funds for public use. To illustrate this point, look at just a few federal allocations in fiscal year 2007, which were based on Census 2000 data.

- Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers – $16.1 billion

- National School Lunch Program – $8.6 billion

- Head Start – $6.2 billion

- State Children’s Insurance Program – $5.5 billion

- Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Program – $5.3 billion

- Foster care (Title IV-E) – $4.5 billion

- Child Care Mandatory and Matching Funds – $2.9 billion

- School Breakfast Program – $2.1 billion

- Food stamps – $30.4 billion

The people served by many of these programs include those in hard-to-count communities who are at greater risk of being missed in the census, thereby skewing predictions of needed resources and potentially skewing appropriations. Mississippi has many people served by these programs.

An additional $12 billion in federal funds was spent in fiscal 2007 on the following projects:

- Unemployment insurance;

- The Workplace Investment Act (provided funding to help adults, dislocated workers, and youth find employment that leads to self-sufficiency through various services available at local support centers);

- The Employment Service (provided a variety of employment-related labor exchange services, including, but not limited to, job search assistance, job referral, and placement assistance for job seekers, re-employment services to unemployment insurance claimants, and recruitment services to employers with job openings);

- The Senior Community Service Employment Program;

- American Indian Employment and Training;

- Prisoner Reentry programs (worked to reduce recidivism by helping former inmates find work when they return to their communities largely through faith-based and community organizations); and,

- Work Opportunity Tax Credit Program (WOTC) and Welfare-to-Work Tax Credit (WtWTC).

These projects also meet the needs and objectives of many Mississippi residents. Of vital interest to constituents with minor children, census data is material to public education. In fiscal year 2007, more than $26 billion in federal funds were allocated to various states to meet the needs of Title I projects (targeted at economically disadvantaged children, vocational rehabilitation, and safe and drug-free school programs), Special Education, Education Technology, and Rural Education grants, all necessary for the improvement of Mississippi’s public education program.

So the simple explanation for conducting the census is that it defines state political representation and a federal funding profile for the next decade.

Lydia Quarles is the senior policy analyst at the John C. Stennis Institute of Government at Mississippi State University.

To learn more about the census, read Census and Redistricting: Just the facts, Ma’am.

-

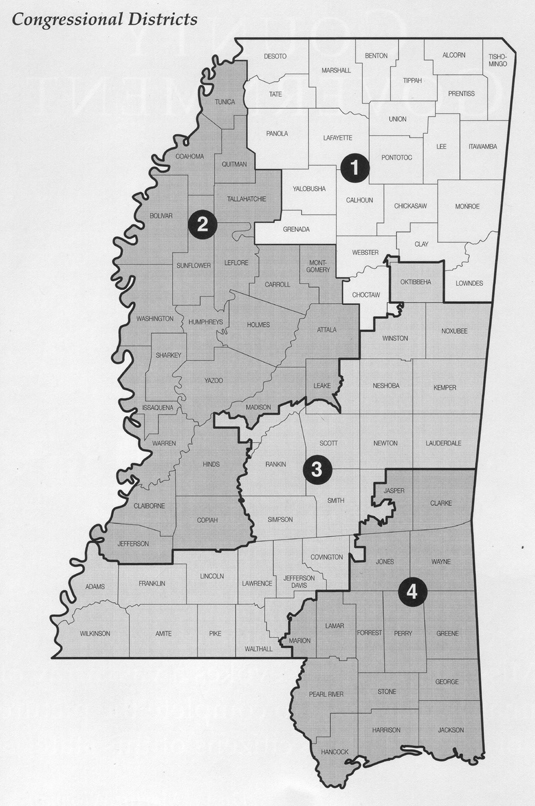

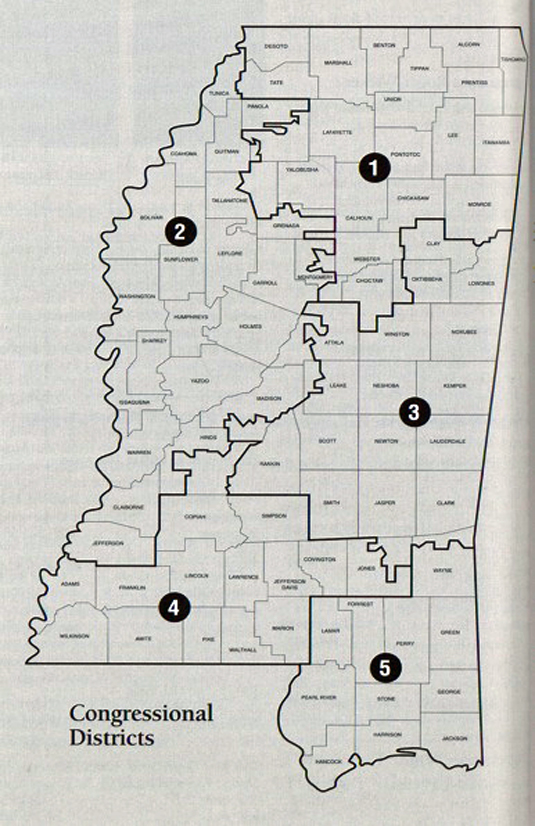

The four U. S. Congressional Districts based on the 2000 census. Map courtesy the Mississippi Secretary of State office. -

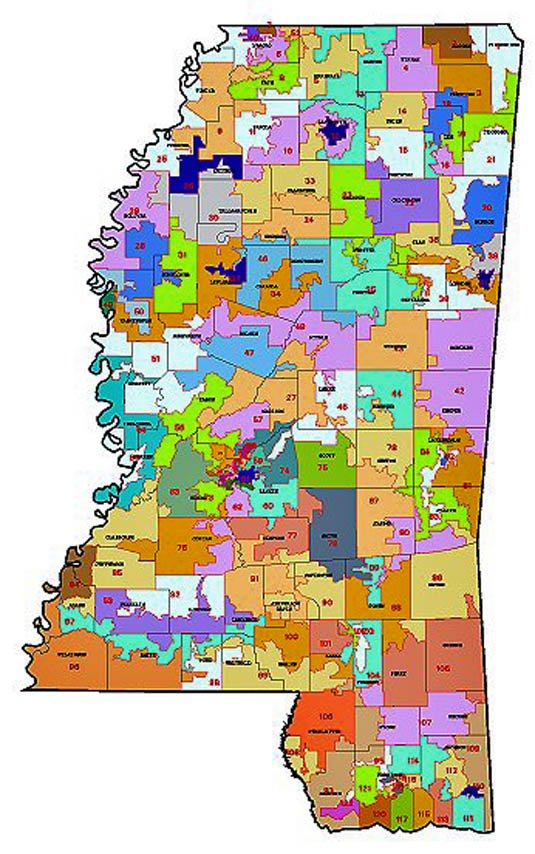

The Mississippi House of Representatives districts based on the 2000 census. Map courtesy the Mississippi Secretary of State office.

-

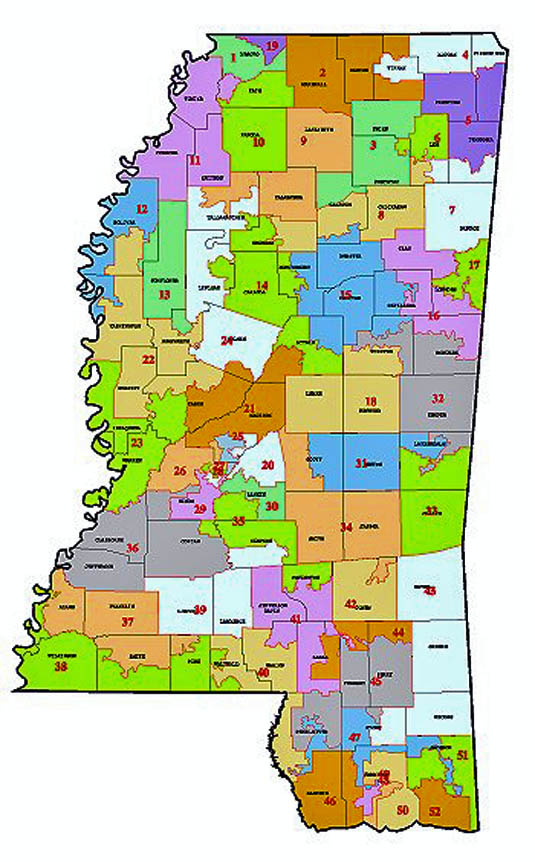

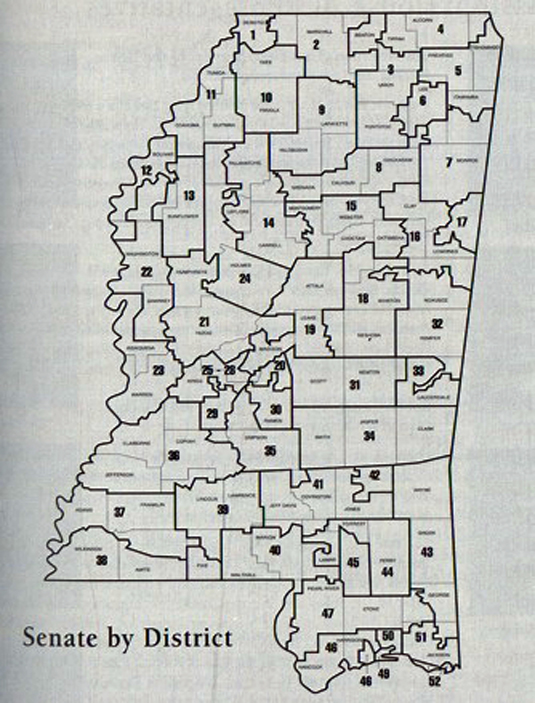

The Mississippi Senate districts based on the 2000 census. Map courtesy the Mississippi Secretary of State office. -

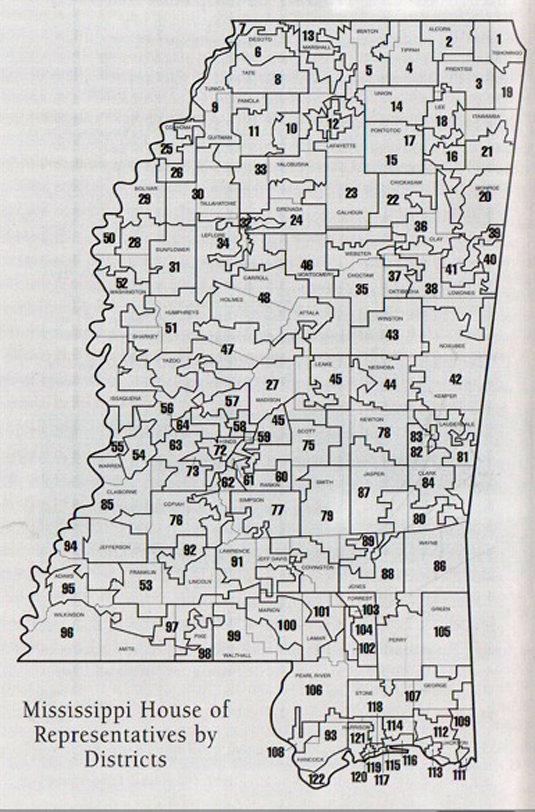

1992 Congressional Districts with 2000 population. Mississippi lost a district after Census 2000. Map courtesy Mississippi Automated Resource Information Center. -

Mississippi House of Representatives districts based on 1990 census. Map from the 1996-2000 Mississippi Official and Statistical Register. Courtesy the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Mississippi Senate districts based on 1990 census. Image from the 1996-2000 Mississippi Official and Statistical Register. Courtesy the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

The five U. S. Congressional Districts based on the 1990 census. Map from the 1996-2000 Mississippi Official and Statistical Register. Courtesy the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.