“Build me straight, O worthy Master!

Stanch and strong, a goodly vessel,

That shall laugh at all disaster

And with wave and whirlwind wrestle!”

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

The economic destiny of the communities of commercial fishermen, net makers, sail makers, seafood factory workers, and boatbuilders on the Mississippi Gulf Coast has always centered around the waterside locations, navigable inland waterways, and the abundance of seafood and other natural resources. Boatyards were a natural extension of these communities, and hundreds of wooden boats were built to seine shrimp, dredge for oysters, and to transport produce.

The tradition of boatbuilding in the coastal region dates back to native peoples and eventually the French settlement on the Mississippi Sound in 1699. The first boat would have been a bateau, a light flat-bottomed riverboat, designed favorable to fishing. Throughout the 18th century and early 19th century, maritime activities such as lumber trade, naval stores, and deer hides, as well as boatbuilding, were important to the area. Ship manifests, particularly those from France, regularly listed carpenters and apprentice ship carpenters, indicating that shipbuilding was a major occupation of the region. The first ship built on the Pascagoula River in present-day Jackson County was a craft constructed in 1772 by the British to transport corn and deerskins.

The catboat

The United States Congress carved the present-day state of Mississippi out of the vast Mississippi Territory in 1817. In the early 19th century, small boatyards existed along the entire Mississippi Gulf Coast. They manufactured and repaired barges and flat-bottomed schooners suitable to the waters of the region. On the Pascagoula River, the Ebenezer Clark Shipyard, north of Moss Point, constructed such vessels, and in addition, records list the repair of some two hundred vessels. Accounts also reveal that Clark Shipyard and Krebs Boatyard, one of the area’s oldest, constructed many small boats and schooners.

In the mid- to late 19th century, the catboat was built and used extensively along the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Catboats were small, wooden fishing boats with a flat bottom, double sails, and could accommodate two fishermen. During the off-season, catboat races often occurred; the first races happened in 1874 in Pascagoula, then a small village on the Pascagoula River and Mississippi Sound. A famous catboat was the Royal Flush, built by Captain Willie Johnson in 1889. Because Captain Johnson constructed her so well, the Royal Flush did not lose a race in thirty-four years.

The Biloxi Schooner

As interest in the seafood industry grew in the late 19th century, fishermen required boats larger than the catboat to haul in the bountiful catches. Schooners, a fast-sailing craft with at least two masts and sails set fore and aft, replaced catboats. The coast schooners were inspired by those used in Baltimore for fishing enterprises carrying goods along sea trade routes, and the tradition of building them was deep in coastal naval enterprises. It was not until 1893 when a hurricane destroyed most of the schooner fleet on the Mississippi Gulf Coast that local boat builders designed a specific style of schooner that was best suited to the waters along the Mississippi coast, waterways that include bayous, oyster reefs, and shallow bays and lakes. The schooner was christened the Biloxi Schooner, a boat characterized by a broad beam, shallow draft, and increased sail power. The schooner was fifty to sixty feet long, although some were larger. Because of its shallow draft, the Biloxi Schooner could easily sail in and out of waters with little depth, and its size allowed larger crews to work on the decks. The sail power of the Biloxi Schooner enabled the ship to drag the oyster dredges and shrimp seines when they became laden with the bivalves and crustaceans. These working crafts were both durable and graceful when “under sail.” In fact, Biloxi Schooners were often referred to as “white-winged queens” as they glided gracefully over the waters in and around the Mississippi Sound with their foresail and mainsail swung out on either side. Apprentice carpenters learning the boatbuilding trade in 1893 could expect to earn 75 cents a day for fifteen hours of work as they worked to replace the lost schooner fleet.

Shipbuilders used local cypress wood for the frames of the schooner. Most of these frame boards were four to five inches thick and set approximately eighteen to fourteen inches apart, depending on the builder. Batten boards were then nailed or bolted to fill in the ribs and to make sure the hull was the correct shape. Caulk was then pounded between the batten boards of the ships to make it airtight. Builders often used Mississippi longleaf yellow pine for the keel, the main structural element of a ship that stretched along the center line of the ship’s bottom from bow to stern, and for its masts and spars, the thick, strong pole used to support the rigging for the “white-winged queens.” Shipbuilders harvested yellow pine from Ship Island, a barrier island approximately twelve miles out in the Gulf of Mexico. Sometimes live oak, another native tree, was used because of its strength. For example, the Gulfport Shipbuilding Company, also on Bayou Bernard, reported on March 4, 1920, that it purchased one piece of live oak, 18 feet by 18 inches, for $36.00. In the early 1900s, the average cost of a schooner was $2,200.

The lugger

The shipbuilding industry would grow side-by-side with the seafood industry as more investors began to see a profitable future in these two businesses. On Bayou Bernard in Handsboro, the Henry Leinhard Shipyard employed Matteo Martinolich in 1889. Martinolich was from Croatia and had learned the shipbuilding trade before he came to America and settled in Mississippi. From 1889 to 1906, he built more than thirty-five registered vessels for Leinhard Shipyard. He later managed the John Francis Stuard Sawmill and Shipyard during World War I (1914-1918); it was also located on Bayou Bernard. The Stuard Shipyard closed in 1920, and Martinolich retired at that time, leaving a legacy of wooden boats plying not only Mississippi waters but international waterways.

By 1915, most fishermen had switched to gasoline-powered boats, the lugger, which could drag the heavy otter trawl, a funnel-shaped net thirty to thirty-five feet long, to efficiently capture more shrimp. In fact, it was J. D. Covacevich who designed the lugger for the fishing industry on the Mississippi Coast. The lugger was sturdy, seaworthy, versatile, and had only a three-foot draw. It became the fishing boat of choice. Shipbuilding was an exclusively male craft with skills learned from generation to generation. Often fathers taught their sons the trade. The Covacevich family, which established their boatyard in 1896 on Back Bay Biloxi, reflects the intergenerational shared knowledge that developed superb shipbuilders. Covacevich was an immigrant from Croatia and passed on his boat-making knowledge to his three sons. The Covacevich Shipyard was the oldest boat-building enterprise on the Biloxi Bay when it stopped building new boats in 1982. The company had built more than a thousand boats, from schooners to World War II mine sweepers to recreational vessels.

During World War II, shipbuilding along the Mississippi Coast evolved to meet the maritime war needs of the nation. Men who once built luggers and other vessels found new employment in shipyards specializing in boats for the war effort. With the war, however, new types of maritime craft were needed, but interestingly, the United States Navy originally needed wooden boats in World War II. Coast shipbuilders answered the call.

Wartime shipbuilding

On October 5, 1940, the Mississippi Legislature passed House Bill 1109 that created the Biloxi Port Commission to help with the growing war effort; this organization was the idea of Biloxians Hart Chinn, J. E. Swetman, and Jacinto Baltar. The commission was empowered to purchase land and build a shipyard to meet the demands of the U.S. Navy’s need for wooden boats At an October 13 meeting, a group of civic-minded men met at the Avelez Hotel and organized the Biloxi Boat Building Corporation. When the corporation experienced financial difficulties, the Bill Kennedy family of Biloxi acquired the interests of the Biloxi Boat Building Corporation and renamed it the Westergard Boat Works of Biloxi. All facilities for the Westergard Boat Works were built from scratch as the company geared up after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Ultimately employing hundreds of workers, the Westergard Boat Works built submarine chasers for the open seas and mine sweepers used in the English Channel. It also constructed hospital ships and repaired PT boats. Seagoing tugboats for firefighting in the invasion of Normandy also rolled off the boatyard’s assembly line and were christened for the war effort.

In Pascagoula, Ingalls Shipbuilding also prepared itself for the war effort. Founded in 1938 by Robert Ingalls from Birmingham, Alabama, and the Ingalls Iron Works, the company first built cargo and passenger ships. Shipbuilding became a major part of Pascagoula’s history since it enjoys two important advantages for transportation ease—a deep-water channel and a railroad. Ingalls began production of ships within one year. In June 1940, Ingalls launched the first all-welded steel ship ever built, the Exchequer. During World War II, Ingalls operated around the clock, building aircraft carriers, troop and cargo transports, net layers, and submarine tenders. Thousands of women helped to build the crafts as men fought overseas. Ingalls built more than sixty ships during the war, and established itself as an innovative and successful operation throughout the 20th century. Litton Industries acquired Ingalls in 1961, and in 2001 Northrop Grumman Corporation acquired Litton. Northrop Grumman is a large international defense contractor based in California. In 2011, Northrop Grumman created a new company, Huntington Ingalls Industries, that now owns the shipyard. The Pascagoula shipyard builds destroyers and guided missile cruisers. It also refurbished the battleship USS Iowa, the only ship of that class that served in the Atlantic Ocean in World War II. The tradition of shipbuilding continues well into the 21st century at this facility.

VT Halter Marine, a shipbuilding subsidiary of Vision Technological Systems, Inc., has a sixty-year history of building a wide variety of vessels. It has three shipyards along the Mississippi coast, in Pascagoula, Moss Point, and Escatapwa. This group has constructed and delivered more than 3,000 vessels to twenty-nine countries.

Trinity Yachts, LLC, founded in 1988, constructs luxury yachts for an international market. Located in Gulfport, this facility was the only company to maintain its operations immediately after Hurricane Katrina in August 2005. Relocating its New Orleans employees after the storm, Trinity Yachts moved a hundred and four house trailers onto its grounds to house four hundred workers who lived and worked on the premises. Moreover, Trinity used yachts to pull four partially completed boats from New Orleans into its Gulfport facility. Today, the company is based entirely in Gulfport and employs approximately 500 workers at any given time. It is a world-renown manufacturer of yachts, patrol boats, tugs, and, in 2010, oil skimmers to meet that need after the British Petroleum oil rig disaster in the Gulf of Mexico in April 2010.

From the industry’s earliest beginnings to today, people on the coast appreciate a well-made boat, whether it is a pleasure craft or an amphibious assault ship. Many coast citizens today still rely upon ships for their livelihood, regardless of the type or function of the craft. The thrill, however, of seeing a Biloxi Schooner move smoothly over the waters of the Mississippi Gulf Coast can still be enjoyed — the Biloxi Seafood and Maritime Museum commissioned local shipbuilders to replicate two sixty-five-foot Biloxi Schooners named the Mike Sekul and the Glenn L Swetman. The Mississippi Coast’s maritime history and heritage of boatbuilding sails on.

Deanne Stephens Nuwer, Ph.D., is associate professor of history and director of the Hurricane Katrina Research Center at the University of Southern Mississippi.

-

By 1915, the lugger replaced the catboat and became the fishing boat of choice. Photograph courtesy Biloxi Public Library. -

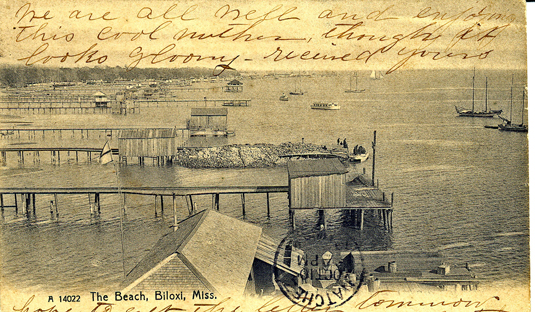

Beachfront along the Mississippi Gulf Coast at Biloxi, circa 1890s. Image courtesy Biloxi Public Library.

-

Biloxi Schooners were often referred to as "white-winged queens." Photograph courtesy Biloxi Public Library. -

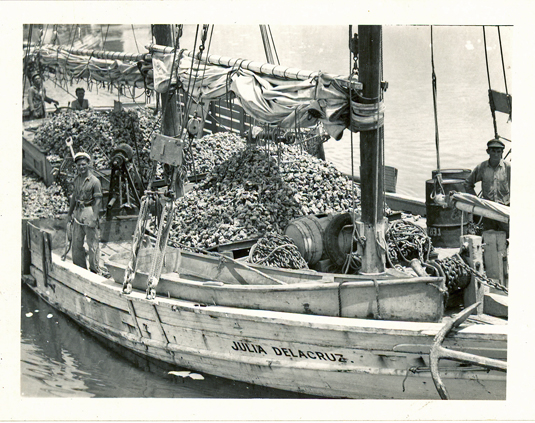

The Julia DelaCruz oyster boat. Photograph courtesy Biloxi Public Library. -

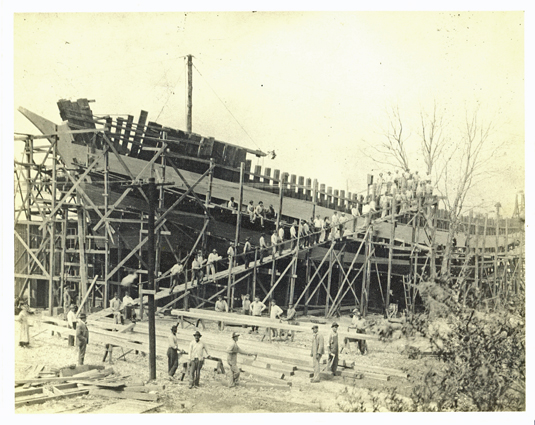

Boatbuilders on the Back Bay of Biloxi, circa 1920s. Photograph courtesy Biloxi Public Library. -

Wartime shipbuilding along the Mississippi Coast. Photograph courtesy Biloxi Public Library. -

A U. S. Navy ship shares port with a shrimp boat. Photograph courtesy Biloxi Public Library. -

The Mike Sekul schooner, commissioned by the Biloxi Seafood and Maritime Museum, still sails the waters on the Mississippi Sound. Photograph courtesy Biloxi Public Library. -

The world-renown Trinity Yachts is based in Gulfport, Mississippi. Photograph courtesy Trinity Yachts. -

VT Halter Marine builds a variety of vessels, among them this Crowley articulated tug/barge. It measures 587 feet in length, 74 feet in breadth, and 40 feet in depth. Photograph courtesy VT Halter Marine.

Sources:

Barnes, Russell E. “Impact of Industrialization on Work and Culture in Biloxi Boatbuilding, 1890-1930,” Thesis, University of Southern Mississippi, 1997.

Ellis, Jamie Bounds and Jane B. Shambra. Biloxi. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

Hubbell, Bill. “Westergard Boat Works,” Biloxi Press, June 15, 1977.

Husley, Val. Maritime Biloxi. Charleston, SC. Arcadia Publishing, 2000.

Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. The Building of the Ship 1849.

Sheffield, David A. and Darnell L. Nicovich. When Biloxi Was the Seafood Capital of the World. Biloxi, Miss.: The City of Biloxi, 1979.

Sullivan, Charles L. and Murella Hebert Powell. The Mississippi Gulf Coast: Portrait of a People. Northridge, CA: Windsor Publications, 1985.

Thompson, Ray M. “The Oldest Boatyard on the Biloxi Bay,” in Down South Magazine, July-August, 1963.

Biloxi Public Library. Ledger Book #2, Vertical File: Boat Building.

William S. Smith, Jr. Vice President of Marketing, Trinity Yachts, LLC. Telephone Interview, September 15, 2010)

Websites (all accessed September 2010):

Ingalls Shipbuilding, Inc.

About Northrop Grumman Shipbuilding.

Deanne Stephens Nuwer, The Seafood Industry in Biloxi: Its Early History, 1848-1930. ed. Peggy Jeanes, Mississippi History Now, June 2006.

Shipbuilding and Marine History On the Pascagoula River & Jackson County, Ms.. Else J. Martin.