United States Senator John Sharp Williams, of Yazoo County, Mississippi, launched his political career in 1892, when he defeated a Populist opponent in his congressional district and entered the United States House of Representatives the following year. The Mississippi Democrat won re-election to Congress seven times before securing a seat in the United States Senate for a six-year term that began in March 1911. He had no opposition in winning a second Senate term and decided to retire when it ended in March 1923. Having spent two years at his plantation home between his terms in the House and Senate, he represented Mississippi in the nation’s capital twenty-eight years and never suffered defeat at the hands of the state’s voters.

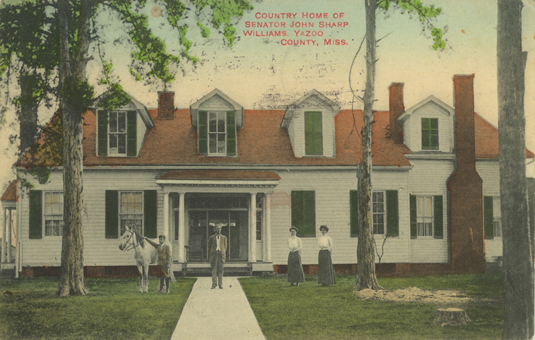

Williams was born July 30, 1854, in Memphis, Tennessee. His mother died in his early childhood, and when his father, a colonel in the Confederate army, was killed in the Battle of Shiloh during the American Civil War, his maternal grandfather, John McNitt Sharp, took him and his younger brother to his Mississippi plantation, Cedar Grove, east of Benton in Yazoo County. His grandfather Sharp, a Confederate officer, also died in the war, and his step-grandmother Sharp took over responsibility for raising and educating him. After graduating from the Kentucky Military Institute in 1870, he attended the University of Virginia and became a Phi Beta Kappa scholar but avoided the required science courses to receive a degree. He studied two years in Europe at the University of Heidelberg in Germany and the College of France at Dijon and returned to the University of Virginia to receive a law degree in 1876. He practiced law briefly in Memphis and married Elizabeth Dial Webb of Livingston, Alabama, before going back to Mississippi to take over management of the Sharp plantation. Over the next fifteen years Williams supervised his planting interests and maintained a law practice in nearby Yazoo City. He and his wife had eight children, four daughters and four sons.

Williams in U.S. House of Representatives

When Williams took his seat in the U. S. House of Representatives in 1893, he quickly won the respect of friends and foes alike for his keen intellect, debating skills, and parliamentary courtesy. He never failed to speak out clearly on the issues and always responded to opponents so that both sides would appear together in the Congressional Record. Williams supported the free coinage of silver, an income tax, and a tariff for revenue only. Believing in a strict interpretation of the U. S. Constitution relating to foreign affairs, he supported independence of Cuba and strongly opposed the United States annexation of Hawaii, Guam, and the Philippine Islands in 1898.

Democrats in the House recognized his loyalty and defense of the principles of Jeffersonian Democracy and elected him minority leader in 1903, 1905, and 1907. Williams served as temporary chairman of the Democratic national convention in 1904, and the party’s platform reflected his moderate, progressive views. He wanted the Democratic Party to shed its negative image and adopt constructive policies that would attract independent voters. Four years later, he supported William Jennings Bryan for the Democratic presidential nomination for the sake of party unity, but he did not admire him and rejected his proposal of government ownership of railroads. Newspapers around the country praised the Mississippi congressman for transforming the party’s unruly membership into an effective, disciplined unit.

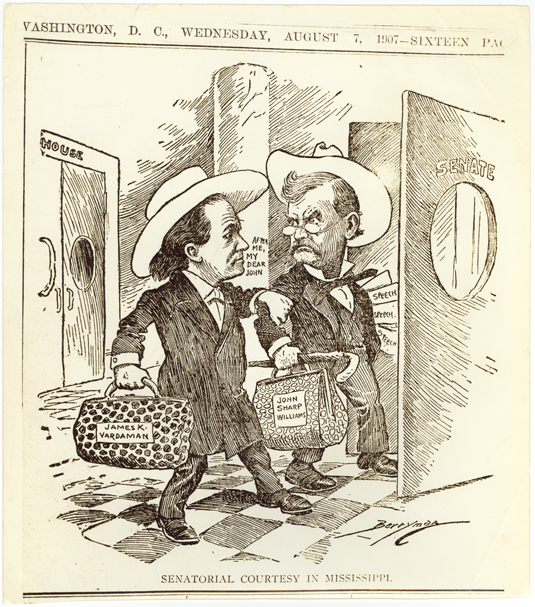

In the Mississippi Democratic primary election of 1907, the race between Congressman John Sharp Williams and Governor James Kimble Vardaman for a full six-year term in the U.S. Senate drew national attention. The New York Times, The Atlanta Constitution, The Washington Post, and many other influential newspapers supported Williams, while William Randolph Hearst’s newspaper chain and Watson’s Jeffersonian Magazine, edited by former Georgia Populist leader Tom Watson, came out for Vardaman. Vardaman called for the repeal of the Fifteenth Amendment, which protected voting rights of African Americans, and “modification” of the Fourteenth, which provided, among other things, a constitutional basis for Black citizenship. In contrast, Williams said that he thought it unwise to re-inject the race question in national politics at a time when Southern congressmen should help to solve the important questions of tariff reform, regulation of trusts, and colonialism. Collier’s, The National Weekly, August 17, 1907, described Williams as “a man of education, wit, and common-sense,” and said that while the congressman “shared the feelings of his neighbors on the race question he had seen enough of other parts of the world to be able to look at that subject in its proper perspective.”

After Williams defeated Vardaman for the Senate by a narrow margin of 648 votes, he received hundreds of letters and telegrams of congratulations from almost every state in the Union. Williams announced after the primary election that he would not seek re-election to his congressional term, which expired in March 1909, because he wanted to spend the two years before the beginning of his Senate term in March 1911 resting and catching up on his reading at his plantation in Yazoo County. The U.S. Constitution required the election of U. S. senators by state legislatures, and the Mississippi Legislature ratified the primary election results and formally elected Williams to the U. S. Senate in January 1908. The Mississippi Constitution of 1890 stated that election of U. S. senators by the legislature to full six-year terms had to take place only in regular sessions, which were held only every four years in the first year of a new four-year administration.

U. S. Senator Williams

John Sharp Williams entered the U. S. Senate April 5, 1911, to attend a special session called by President William Howard Taft. In debate on the proposed constitutional amendment for direct election of senators by the people rather than election by state legislators, he broke the long-standing custom for new members to keep silent in their first session by announcing his unqualified support of the measure. In the July 22, 1911, edition of The Saturday Evening Post, a reporter observed that Williams had not changed in his two-year absence from Washington: “He is the same whimsical, delightful, brilliant chap he always was – absent-minded, preoccupied, unimpressed by any but the essentials, careless, happy-go-lucky, and smarter than a steel trap.”

The new senator received assignments to the Finance Committee and Foreign Relations Committee. He had always advocated fiscal responsibility and kept a close eye on foreign affairs. Williams had served for a number of years on the executive committee of the American group of the Inter-Parliamentary Union for International Peace, and he also became a trustee of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace when it was established in 1910.

Williams supported Woodrow Wilson for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1912, and served on his executive campaign committee in the East. He urged Wilson’s election because he thought he met the Jeffersonian standards of competency, faithfulness, and honesty in public officials. He interrupted his schedule of campaign speeches for Wilson to deliver a series of lectures on Thomas Jefferson at Columbia University. These were edited and published in 1913 as a book, Thomas Jefferson, His Permanent Influence on American Institutions.

Senator Williams believed in teamwork, and during Wilson’s two terms as president he was one of his most loyal supporters and friends. He worked hard for tariff reform, imposition of an income tax, anti-trust legislation, and an overhaul of the banking system. When opposition from the legal profession and businessmen arose to the president’s appointment of Louis Brandeis to the U. S. Supreme Court, Williams announced that he would vote for his confirmation because he did not think a man’s liberal academic views should be held against him if he were honest and a good lawyer. He was in full accord with President Wilson’s consideration of moral values in the conduct of foreign policy, and his refusal to recognize a Mexican government controlled by General Victoriano Huerta who had seized power by violent and illegal means.

The respect and confidence that Mississippians had in Senator Williams was evident in 1916 when he drew no opposition in his bid for re-election. He campaigned in the states of Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Illinois for President Wilson’s re-election. In September 1916, President Wilson and Williams traveled to Hodgenville, Kentucky, where they both spoke at the dedication of the Abraham Lincoln birthplace shrine. The Mississippi senator praised Lincoln as one of the greatest Americans and said that he was much like Thomas Jefferson, in that both were idealists and statesmen.

After the Great War broke out in Europe in 1914, Williams agreed with the president’s policies in dealing with violations of American neutral rights by both sides, and he strongly supported the president’s decision to hold Germany to strict accountability for the loss of American lives and property in submarine warfare. He accused those senators who opposed a declaration of war in April 1917 of “grazing on the edge of treason.” Frustrated and disappointed after waging a hard, unsuccessful fight for ratification of the Versailles Treaty and the League of Nations, Williams told his friends that it might be necessary for another great war to occur to convince America’s leaders to make some concessions to preserve world peace.

Williams personally opposed Prohibition — the outlawing of alcoholic beverages — but he explained that he voted for the Eighteenth Amendment because most Mississippians favored it. Independent of thought and action, however, the senator’s votes did not always reflect the popular opinion of the state’s citizens. After the war, for example, he opposed bonuses to able-bodied veterans because he thought patriotism should carry no price tag. In an uncharacteristic and unstatesmanlike stand, Williams, along with some other southern senators, opposed the Nineteenth Amendment, which gave women the right to vote, on grounds that the time was not right to enfranchise Black women because it might pose a threat to White political supremacy in the South.

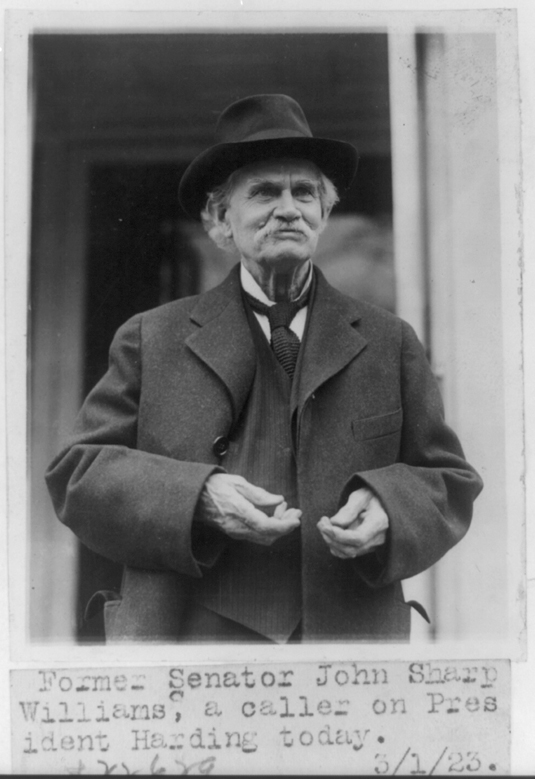

Like other Mississippi politicians, Williams believed in White supremacy, but he never exploited the race issue for political gain. In forwarding a letter to President Warren G. Harding from Isaiah T. Montgomery, one of Mississippi’s most respected Black leaders, asking the senator to help his son-in-law, Eugene P. Booze, get an appointment with the president, Williams wrote that he was “in absolute accord with the desire expressed by Isaiah Montgomery of doing all that I can to cultivate confidence and good will between the races of my state . . . . and to encourage the development of the Negro race so that it may be . . . . lifted to a plane where it can take a good part in the . . . . development of the country . . . .”

Williams in retirement

Williams did not seek re-election to a third term in 1922. Shortly after his election to a second term, he had announced that he would not run again, and he could not be persuaded by repeated requests of friends and supporters to change his mind. He had become hard of hearing and did not feel that he could continue to meet effectively the demands of political life. In March 1923, he left Washington and returned to his Mississippi plantation to read books, write letters, and enjoy nine years of retirement with family and friends. He made his last formal speech at the dedication of a monument to Jefferson Davis at the Vicksburg National Military Park in October 1927.

John Sharp Williams had his faults and weaknesses, but most political observers of that day characterized him as a statesman and a scholar who projected a positive image for the State of Mississippi over the course of his career. The New York Times, on October 2, 1932, reported that in a interview shortly before his death, he said, “I think that if a man can get to my age and looking back, believe a majority of things he did were worth the effort, he has nothing to regret.”

Thomas N. Boschert, Ph.D, is visiting assistant professor of history, Delta State University, Cleveland, Mississippi.

Lesson Plan

-

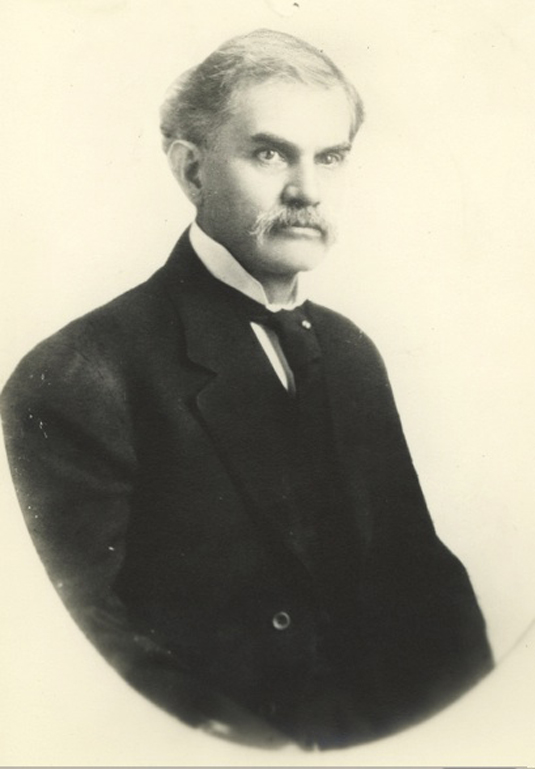

John Sharp Williams. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/PER/W56/No. 3. -

Cedar Grove, the plantation home of John Sharp Williams in Yazoo County. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/1992.0001/3201.

-

"Senatorial Courtesy in Mississippi" reads the cartoon depicting John Sharp Williams and James K. Vardaman during the 1907 Senate campaign. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/Z/220.1/Box 589/No. 13. -

John Sharp Williams at the Senate Office Building, Washington, D. C., in 1920. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/POL/1981.0078/No. 2. -

John Sharp Williams leaves the White House, March 1, 1923, after calling on President Warren G. Harding. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-39622. -

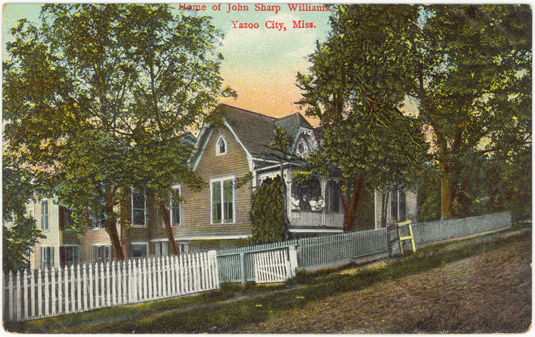

The Yazoo County home of John Sharp Williams. It was built in 1832. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/1992.0001/3200.

Bibliography

Boschert, Thomas N. “A Family Affair: Mississippi Politics, 1882-1932.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Mississippi, 1995.

Dickson, Harris. An Old-Fashioned Senator. New York. Frederick A. Stokes. 1925.

Grantham Jr., Dewey W. Hoke Smith and the Politics of the New South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana University Press, 1958.

Mississippi Department of Archives and History. The Official and Statistical Register of the State of Mississippi (1920-1924). Compiled by Dunbar Rowland. Jackson, Mississippi, 1923.

Osborn, George Coleman. John Sharp Williams: Planter-Statesman of the Deep South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana University Press, 1943.

Rand, Clayton. Men of Spine in Mississippi. Gulfport: The Dixie Press, 1940.

Williams, John Sharp. Lincoln Birthplace Farm at Hodgenville, Ky: Address Delivered on the Occasion of the Acceptance of a Deed of Gift to the Nation by the Lincoln Farm Association of the Lincoln Birthplace Farm at Hodgenville, Ky. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1916.