“Richmond and Corinth are now the great strategical points of war, and our success at these points should be insured at all hazards,” declared a Union general early in the American Civil War. A Confederate general agreed, saying, “If defeated here [Corinth], we lose the Mississippi Valley and probably our cause.”

Sieges, battles, and skirmishes were all fought in and around Corinth during the war, and the South lost each time. As the Confederate general predicted, the South thus lost the Mississippi Valley and the war. How much of a role Corinth’s military history played in the Confederacy’s defeat has been long debated by historians, but it is obvious that the Southern defeats in north Mississippi did not help their cause at all.

The main reason for Corinth’s military importance was because two major railroads, the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, running east and west, and the Mobile and Ohio Railroad, running north and south, crossed in its downtown. The relatively new transportation technologies, steamboats and railroads, revolutionized the art of war. These two railroads were perhaps the most important in the Confederacy because they extended nearly the entire height and breadth of the South. One Southern officer described them, in fact, as “the vertebrae of the Confederacy.”

The important crossroads town of Corinth, located in northeast Mississippi, contained over a thousand inhabitants when the Civil War began, and some of the fighting took place inside its limits. The structural damage and the dead and wounded left behind had a tremendous effect on the local population. Many houses, churches, and hotels became hospitals and many inhabitants cared for the wounded. As the town changed hands during the war, White residents sometimes found themselves under Union occupation while African Americans had their first taste of freedom in a “contraband” camp.

Confederate mobilization: Railroads and Shiloh

The story of Corinth in the Civil War began years before the conflict erupted. When railroad officials determined that two lines would cross there, the city’s fate was determined. Corinth sprouted while the railroads were being finished in the late 1850s and it quickly became a target when the war began.

Corinth’s railroads became especially busy early in the conflict, as the state of Mississippi and the Confederate government shipped troops, arms, food, and ordnance all over the Confederacy. Indeed, Corinth became a favorite area of mobilization for the Confederate war effort.

As Union forces made steady gains in Kentucky and Tennessee, they began to set their sights on Corinth’s railroads. The plan was to take the crossing point and thus deprive the Confederates of the railroads’ logistical benefit. As the Union military drew nearer to Corinth, the Confederates added more men and materiel to defend it. By April 1862, General Ulysses S. Grant’s Union Army of the Tennessee was within twenty miles of Corinth, while the majority of General Albert Sidney Johnston’s Confederate Army of the Mississippi held the city itself. The Battle of Shiloh on April 6-7, 1862, in which the Confederates surprised the enemy at nearby Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee, in an effort to defend Corinth, was actually fought over possession of the city’s railroads.

The Confederates lost the Battle of Shiloh and had to retreat to Corinth, bringing many of their wounded with them. Corinth became one vast hospital. The victorious and reinforced Union armies allowed the bloodied Southerners little respite, however, and followed the Confederates to Corinth, laying siege to the town in May 1862.

Union occupation: The siege and battle

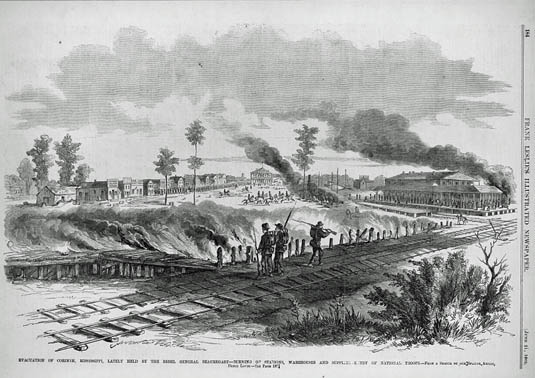

By the end of May, the 120,000-man Union force occupied a semi-circle around the north and east portions of Corinth. Dug into entrenchments and with heavy artillery ready to blast Corinth’s defenders, Union soldiers under General Henry W. Halleck were confident of victory. The Confederate army, under General P.G.T. Beauregard, knew they could not withstand the Union assault. In an elaborate game of trickery and deception, they retreated rather than surrender (as many Confederate armies did after a siege), leaving the town and its citizens to the enemy on May 30, 1862. Despite an earlier order for all citizens to evacuate, many did not and they came under Union occupation.

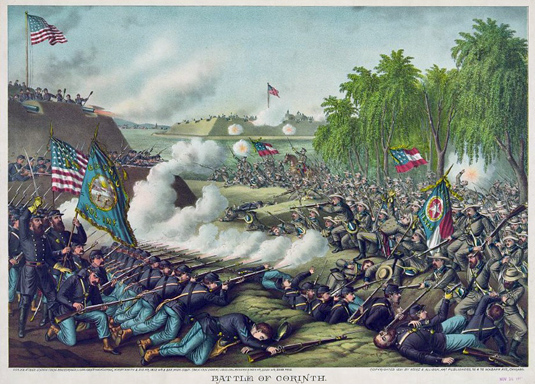

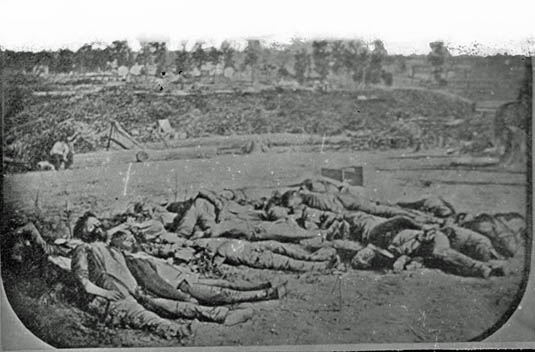

The Confederates were not willing to allow the enemy to keep Corinth and her railroads, however. After a summer of relative inactivity, the Southerners, now under General Earl Van Dorn, attacked the city in October 1862, hoping to drive General William S. Rosecrans’ Union soldiers out of town and retake the lost railroads. In a bloody battle on October 3-4, 1862, fighting raged all around Corinth to the north and west, and at times right into the very heart of downtown. Confederates penetrated several forts along the periphery of the town, including Battery Powell and Battery Robinett, and broke through the center all the way into downtown, where fighting raged around the railroad crossing and the nearby Tishomingo Hotel. Union soldiers retook their positions in a counterattack and drove off the Confederates, but at the cost of thousands of dead and wounded on each side. The buildings and citizens of Corinth, those who remained, were once again inundated with dead and wounded soldiers.

Once the fighting ended, there were no more Confederate attempts to recapture the town. The Union military then used Corinth and her railroads in relative safety for much of the remainder of the war, shuttling troops from theater to theater. During this time, a large garrison held the town, and it also became a major supply center for the area.

The local enslaved population, either freed by the Union army or escapees to Union lines, were gathered in a “contraband camp,” actually a small city in itself just east of Corinth. Many freedmen at the camp were formed into the 55th Regiment Infantry, United States Colored Troops. Commanded by White officers, the regiment served the remainder of the war at various locations, mostly doing garrison and guard duty.

Confederate return: End of the war and memory

By January 1864, the strategic situation had changed so much that Corinth was no longer needed by the Union, so the Federal army abandoned the town. The contraband camp was moved to Memphis, Tennessee, and Confederate military units returned to the city. But years of war and occupation had taken its toll, and Corinth would not serve a major role for the remainder of the war. The one exception was that the Confederate Army of Tennessee camped there a short time in the winter of 1864-1865 after its disastrous invasion of Tennessee and defeats at Franklin and Nashville.

The story of Corinth in the Civil War, therefore, is a tale of fighting, occupation, and carnage. But it is also a story of courage and freedom. In order to mark and interpret these Civil War events, the Federal government has taken several steps through the years. The twenty-acre Corinth National Cemetery, established in 1866 immediately after the war, contains the remains of nearly six thousand Union soldiers who fought at Corinth and in the surrounding area. There are also a few Confederates within its walls, but most Confederates are buried in long-lost mass graves around the town.

In the ensuing years, local preservation efforts marked several sites related to the siege and battle, but it was in 2004 that the National Park Service opened an interpretive center in Corinth. A unit of nearby Shiloh National Military Park, this visitor center sits at the site of the climactic fight at Battery Robinett and interprets Corinth’s rich Civil War history. It provides the visitor insight into the many different facets of war that occurred in this northeast Mississippi town that once sat at the crossroads of history.

Timothy B. Smith, Ph.D., is a veteran of the National Park Service (Shiloh National Military Park) who now teaches at the University of Tennessee at Martin. He is working on a study of Mississippi’s homefront during the Civil War for the Mississippi Heritage Series, and is also nearing completion of a study of Corinth in the Civil War.

Lesson Plan

-

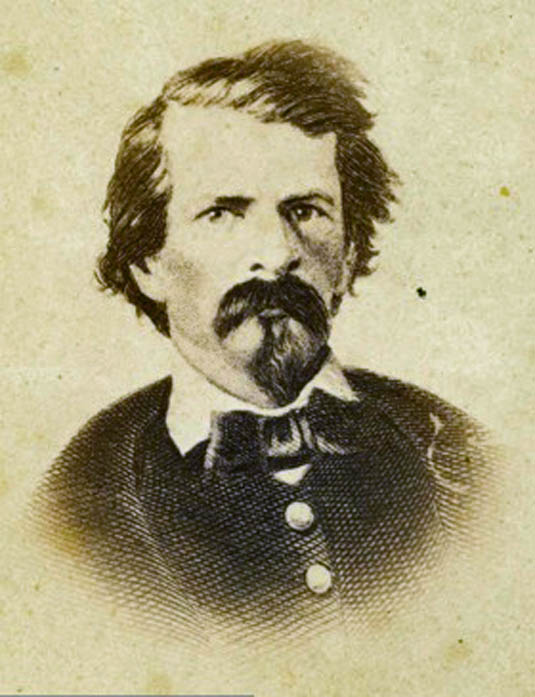

Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston. His Army of the Mississippi held Corinth in April 1862 at the time Union General Ulysses S. Grant's Army of the Tennessee was within 20 miles. Photograph courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/1985.0017, No. 34. -

Union General Henry Wager Halleck. Union soldiers under the command of General Halleck followed Confederates to Corinth after the Confederates lost the Battle of Shiloh in April. Halleck and his army lay siege to Corinth in May 1862. Photograph courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-08361.

-

Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard. In May 1862, General Beauregard, in an elaborate game of trickery and deception, evacuated Confederate soldiers from Corinth, rather than surrender. Photograph courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/1985.0017, No. 12. -

The May 1862 Confederate evacuation of Corinth and the burning of its warehouses and supplies. Image courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-132568. -

Confederate General Earl Van Dorn. The Confederates under General Van Dorn tried to recapture Corinth and retake the railroads in a bloody battle on October 3-4, 1862. The Union Army counterattacked and drove off the Confederates. Photograph courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/1985.0017, No. 48. -

Battle of Corinth, October 3-4, 1862. Image courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-01847. -

Confederate dead in front of Battery Robinette the morning after the October 4, 1862, attack. The October battle left thousands of dead and wounded soldiers on each side. Image courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-B811-1292. -

The Curlee House in Corinth served as headquarters for Union General Halleck and later for Confederate General Earl Van Dorn. Today the house is the City of Corinth's Verandah/Curlee House Museum. Photograph courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/2004.0018, No. 4.

Selected Bibliography:

Allen, Stacy D. “Crossroads of the Western Confederacy.” Blue and Gray Magazine 19, No. 6 (Summer 2002): 6-51.

Cozzens, Peter. The Darkest Days of the War: The Battles of Iuka & Corinth. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Dossman, Steven Nathaniel. Campaign for Corinth: Blood in Mississippi. Abilene: McWhiney Foundation Press, 2006.

Hess, Earl J. Banners to the Breeze: The Kentucky Campaign, Corinth, and Stones River. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

Marszalek, John F. “Halleck Captures Corinth,” Civil War Times 45 (February 2006): 46-52.

Smith, Timothy B. “A Siege From the Start: The Spring 1862 Campaign against Corinth, Mississippi.” Journal of Mississippi History, Vol. 66, No. 4 (2004): 403-424.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. 128 volumes in four series. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901. Series 1, Volume 10 covers the Siege of Corinth while Series 1, Volume 17 covers the Battle of Corinth.