In its 19th century beginning, the seafood industry in Biloxi, Mississippi, supplied only local markets with its succulent shrimp and plump oysters, and coast residents had always enjoyed the bounty of the harvest. Located on the water’s edge of the Gulf of Mexico, the city erected the Biloxi Lighthouse in 1848 to guide fishermen safely home. Locally caught and processed seafood could not be shipped to any market of great distance since there was no way to prevent spoilage. Nevertheless, with the burgeoning tourist trade from New Orleans, Louisiana, in the late 1860s Biloxi and the Mississippi Coast’s seafood industry had ready markets, albeit limited ones.

Then, in 1870, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad joined the cities of New Orleans and Mobile, Alabama, and brought an even larger market for tourists in Biloxi and a better mode of transportation for locally harvested seafood. Moreover, with the invention of artificial ice in the mid-19th century, broader commercialization of Biloxi’s seafood industry became possible.

The canning factory

With the expanded coastal railroad service and the introduction of ice for refrigeration, Biloxi businessmen Lazaro Lopez, F. William Elmer, W. K. M. Dukate, William Gorenflo, and James Maycock invested $8,000 and opened the Lopez, Elmer & Company seafood plant, the first oyster packing enterprise in Biloxi. The men planned to profit from the abundant availability of seafood in the Gulf waters and to catch the rising tide of a developing industry. The facility opened at the foot of Reynoir Street in 1881, on Back Bay Biloxi. It canned oysters and shrimp and offered raw oysters in bulk.

Once the canning factory opened, Dukate traveled to Baltimore, Maryland, to study oyster and shrimp canning methods used in that already booming seafood processing area. There he learned the latest methods of canning oysters and shrimp and discovered that the factories also used a seasonal labor pool, the “Bohemians” or Polish workers. Upon returning to Biloxi, Dukate shared his knowledge of improved processes with his partners, along with information about the Polish workers. Subsequently, Lopez, Elmer & Company initiated improvements and experienced great success, spawning the rapid organization of other seafood endeavors by entrepreneurs. In the early 1880s, Biloxi’s population was approximately 1,500; however, by 1890, it had jumped to about 3,000. The expanding seafood industry doubled the population of the city since the seafood factories needed more workers to process the plentiful catches of shrimp and oysters.

The workers

The first workers in the factories were the migrant Bohemians from Baltimore whom Dukate had seen in that city. Arrangements were made between seafood factory owners in Biloxi to coordinate the transporting of the workers by boxcar from Baltimore factories to Biloxi facilities. On January 11, 1890, The Daily Herald reported the arrival of the first “Bohemian” workers into Biloxi’s Point Cadet area. Rows of shotgun clapboard houses, collectively referred to as camps, had been built by the factories’ owners to lodge the seasonal workers. Locals christened the seafood camps the “Hotel d’Bohemia.” One Biloxian, Amelia “Sis” Eleuteris, recalled that the Polish workers spoke English and “were good-natured people.” However, according to Eleuteris, the Polish workers’ wages were “pitiful,” since the cost of their transportation to Biloxi was deducted from their wages. Yet, the workers continued to migrate to Biloxi for twenty-eight years as itinerant laborers. Biloxi’s seafood industry continued to expand, harvesting the seemingly never-ending catches in the Gulf of Mexico and its numerous bays and bayous.

Seafood capital of the world

In 1890, an annual processing of two million pounds of oysters and 614,000 pounds of shrimp was reported by Biloxi’s canneries. By 1902, those numbers had skyrocketed as twelve canneries reported a combined catch of 5,988,788 pounds of oysters and 4,424,000 pounds of shrimp. By 1903, Biloxi, with a population of approximately 8,000, was referred to as “The Seafood Capital of the World.”

Seafood cannery owners sent out their boats, beautiful “white-winged” Biloxi schooners and others, to ply the waters for their bounties. Each seafood cannery engaged its own fleet, sometimes as many as 150 boats, in order to earn maximum profits and perhaps control the harvests. In the early 1900s, the cost of a schooner was approximately $2,200. The seafood workers who packed the catches and the fishermen who caught the shrimp and tonged the oysters were usually not able to afford their own boats, therefore, factory owners owned and controlled the fleets and harvests.

Owners began to use a new labor source, the Slavic nationalities from the Dalmatian Coast on the Adriatic Sea. They had migrated to the Biloxi region before the turn of the century, seeking political asylum from the troubled Austro-Hungarian empire and employment akin to their native pursuit of fishing. Consequently, Biloxi was flourishing. These cultural groups, along with Louisianans of French descent who arrived in Biloxi about 1910, worked together in the seafood factories and co-mingled in the hardscrabble fishing life. The vast seafood workforce, often reaching a thousand at one cannery, for example, was divided into distinct labor divisions. Schooner oystermen tonged for the bivalves during the winter months and shrimpers trawled for the crustaceans during the summer. They brought in their catches to the many seafood factories along Biloxi’s Back Bay or Front Beach.

Prices for shrimp and oysters

The price of oysters and shrimp off the boats varied from year to year, depending upon the market and ecological conditions. For example, in 1908, oystermen received eleven cents per pound, but by 1918, the price was down to three cents per pound. Shrimp prices averaged $3.00 for a two hundred-pound barrel. As the ships reached port, each factory’s distinctive whistle pierced the air, calling those shrimp or oyster workers to begin the process of unloading, cleaning, and packing. The oyster and shrimp work was always separate. All seafood factories dealt with both resources, but they accepted only one canning and packing endeavor at a time, as the shrimp and oyster seasons varied.

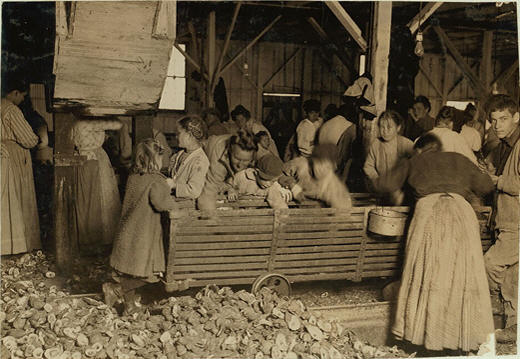

Workers inside the factory, who canned and packed, were paid by the hour, while those who worked outside, cleaning and shucking, were paid by the pound. Oyster shuckers had a one-half gallon bucket that they were expected to fill, and shrimp pickers had a metal “cup” that held approximately ten pounds of shelled shrimp. Both containers had holes in the bottoms so that the natural juices could drain. Once the shrimp were shelled and the oysters were shucked, the seafood was canned. Hourly rates varied from year to year; Eleuteris reported 20 cents per hour, while Teresa Croncich Ewing, who was born in Biloxi in 1898 and worked in the seafood industry all her life, reported earning only 10 cents per hour. Regardless of the salary, whether by barrel weight, poundage, or hourly rate, all seafood work was physically demanding.

The boats

The various ethnic groups who worked on the factory-owned Biloxi schooners and on newly developed gasoline-powered shrimpers, amply supplied the canneries with shrimp and oysters. With the advent of newer and more efficient boats, however, the Biloxi schooners’ popularity and usefulness waned. Around 1914, shrimpers began to favor gasoline-powered boats since they could drag heavy trawl nets. The otter trawl, a funnel-shaped net thirty to thirty-five feet long, required only two men to handle it from the boat, whereas the older seine nets, which were often up to twelve hundred feet long, required as many as six men to haul them onto the boat. Power boats could trawl with the otter net and bring in more harvest with fewer men. As a result, schooner production in Biloxi fell from 327 in 1906 to 277 by 1914, while motor-powered fishing vessels increased from 78 to 106. The last working seafood schooner in Biloxi was the Mary Margaret, built at Jacky Jack Covacevich’s Back Bay boatyard in 1929.

With the demise of the schooner, trawling technology continued to improve through the 1920s as a smaller gasoline-powered boat called a lugger came into use. The lugger was a low, sturdy, wide-beamed fishing boat ideally suited to the shoal waters of the Mississippi Sound. Inspired by Slavonian design, this craft proved to be an evolutionary replacement for the schooner and power boats. Luggers brought in greater catches; they were more powerful and required fewer men to work the nets. As schooners were much bigger than the lugger and required larger crews, factory owners divested themselves of their schooner fleets – in fact, in 1920, only 241 schooners remained out of the vast fleets of just thirty years earlier – but factory owners did not invest in luggers. After World War I as the seafood market floundered, local fishermen were able to purchase or finance the less expensive luggers individually, or in partnerships, and began harvesting shrimp and oysters to sell to the seafood factories that survived the tide of economic change. The cost of a lugger averaged approximately $800 if it was not outfitted with an engine and other equipment – $1,000 if sea-ready. As a result, “shrimp boat ownership shifted from factories to fishermen,” recalled Biloxians JoLyn and Jack Covacevich.

A family affair

Entire families worked in the industry, with a clear division of labor along gender lines. The male members of a household were boat owners or fishermen, while women and children of the family usually worked in the factories. Young children worked alongside adults until a 1908 Mississippi law made it illegal to hire children under age 12 to work in factories. The success of the seafood harvest was dependent on the entire family.

Although the seafood market suffered during and after World War I, in 1930 local citizens created the Seafood Festival to emphasize the importance of the seafood industry in Biloxi and perhaps to help the market. On September 26 that same year, Biloxi’s canneries reported that 20,000,000 cans of oysters and shrimp had been packed and 17,000 gallons of raw oysters had been shipped out of the city.

Biloxi’s seafood industry had experienced many transformations and labor struggles between fishermen and factory owners in the early 20th century, but regardless of its history, the seafood industry was a vital part of the Mississippi Gulf Coast economy and a powerful influence in the cultural fabric of the city of Biloxi.

Deanne Stephens Nuwer, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of history at the University of Southern Mississippi.

This article is an excerpt from Dr. Nuwer’s original one that appeared in The Journal of Mississippi History, Volume LXVI, No. 4, Winter 2004, under the title, “The Biloxi Fishermen Are Killing the Goose that Laid the Golden Egg:” The Seafood Strike of 1932. Used by permission of The Journal of Mississippi History.

Lesson Plan

-

The coast at Biloxi, circa 1901. Coast residents had always enjoyed shrimp and oysters from the Gulf of Mexico waters. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Call no. LC-D4-10566L -

In 1848 Biloxi erected a lighthouse to guide fishermen safely home. Photograph of the Biloxi Lighthouse circa 1901. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Call no. LC-DIG-det-4a08958

-

Factory owners built rows of shotgun clapboard houses, collectively referred to as camps, to lodge seasonal workers. Shown here is one of the labor camps for workers at Peerless Oyster Company in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi. About 18 families lived here. March 1911 photograph by Lewis Wickes Hine. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Call no. LC-DIG-nclc-00902 -

Dunbar & Dukate Oyster Cannery in Biloxi. February 1916 photograph by Lewis Wickes Hine. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Call no. LC-DIG-nclc-01036 -

Shrimp-pickers at Gorenflo Canning Company in Biloxi. Photograph taken at 7 a.m., March 1911, by Lewis Wickes Hine. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Call no. LC-DIG-nclc-00783 -

Oyster-shuckers in Barataria Canning Company in Biloxi. February 1911 photograph by Lewis Wickes Hine. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Call no. LC-DIG-nclc-00822 -

Oyster fishing schooner sails on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, call no. PI/1991.0005/1

References:

Barnes, Russell E. The Impact on Work and Culture in Biloxi Boatbuilding 1890-1930. Thesis. Hattiesburg, Miss.: University of Southern Mississippi, 1997

Covacevich, JoLyn and Jack, telephone interview by author, January 20, 2003

Desporte, Janie and Artie, telephone interview by author, January 8, 2003

Eleuteris, Amelia “Sis,” Oral History Interview, June 1975, Biloxi Public Library Oral History Collection

Ewing, Teresa Croncich, Oral History Interview, June 24, 1975, Biloxi Public Library Oral History Collection

Sheffield, David A. and Darnell L. Nicovich. When Biloxi Was the Seafood Capital of the World, ed. Julia Cook Guice. Biloxi, Miss.: City of Biloxi, 1979

Sullivan, Charles and Murella Hebert Powell. The Mississippi Gulf Coast: Portrait of a People. Northridge: Windsor Publications, 1985