General William Tecumseh Sherman is probably best remembered for his spectacular 1864 “March to the Sea” in which he stormed 225 miles through Georgia with no line of communication in a Union campaign to take the American Civil War to the Confederate population. Sherman, however, was not always so daring and independent, but rather he was a general who profoundly grew and developed during the Civil War.

One critical phase of this growth was Sherman’s successful Meridian Campaign in February 1864. It was on this raid to protect the Mississippi River from Confederate guerillas that Sherman first demonstrated the ability to operate independently deep in enemy territory, far from headquarters. It was on this raid that Sherman pioneered the art of destroying Confederate war-making capability.

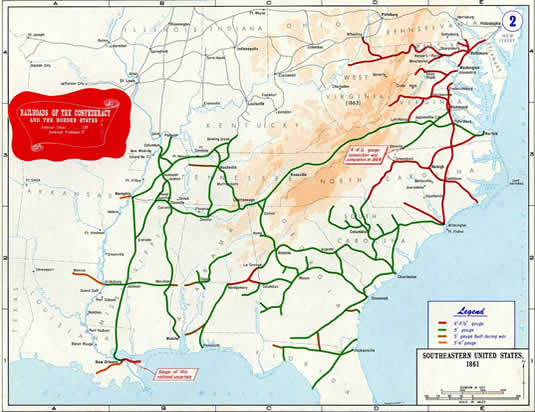

Meridian, where three railroads intersected, was a Confederate strategic point, lying roughly between the Mississippi capital of Jackson and the cannon foundry and manufacturing center of Selma, Alabama. It served as a storage and distribution center for not just the industrial products of Selma, but for grain and cattle from the fertile Black Prairie region to the immediate north. It all presented a tempting target for Sherman who did not want to sit idle waiting for weather sufficient to support the upcoming spring campaign.

Meridian was about 150 miles from Sherman’s location at Vicksburg that the Union had taken the previous summer in order to gain control of the Mississippi River. Sherman figured it would be an easy matter to finish his business in Meridian in plenty of time to return to Vicksburg and be ready for future operations; a precondition that Sherman’s commander, General Ulysses S. Grant, had given him. Thus, on February 3, he began his campaign “to break up the enemy’s railroads at and about Meridian, and to do the enemy as much damage as possible in the month of February, and to be prepared by the 1st of March to assist General [Nathaniel] Banks in a similar dash at the Red River [Louisiana] country…”

A graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, Sherman’s execution would be brilliant and it is a classic example of an operation that makes best use of the traditional characteristics of the offensive: audacity, tempo, surprise, and concentration.

Audacity: a simple plan of action, boldly executed.

Sherman’s military genius lay more in maneuver and logistics — preserving his own and disrupting his enemy’s — than it did in tactics. The Meridian Campaign is a case study in such methodology, but certainly not one without enormous risk. Sherman would be marching some 150 miles from his Vicksburg base, living off the land, and exposing himself to a potential Confederate concentration from three directions. If the Confederates were able to unite against him, Sherman’s entire army would face annihilation. It was an undertaking that caused “much anxiety” in Washington, but Sherman’s commander was not worried. Grant knew that any risk was lessened by the fact that Sherman, as the raider, could choose his line of retreat. Grant was confident Sherman would “find an outlet. If in no other way, he will fall back on Pascagoula, and ship from there under protection of [Admiral David] Farragut’s fleet.” For Archer Jones, historian of Civil War strategy, any threat was alleviated by “the offensive dominance of the raid over a persisting [territorially based] defense.”

Audacious commanders take prudent risks in order to achieve decisive results and dispel uncertainty through action. At Meridian and elsewhere, Sherman epitomized audacity.

Tempo: a faster tempo allows attackers to disrupt enemy defensive plans by achieving results quicker than the enemy can respond.

Sherman knew that his success would depend on speed. He would travel light, ordering, “Not a tent will be carried, from the commander-in- chief down.” He explained, “The expedition is one of celerity, and all things must tend to that.”

Sherman began his march in two columns of a corps each in order to facilitate both speed and foraging. Sherman’s army would be living off the land — this would keep important supplies from the Confederate Army and would also force Sherman to keep moving in search of more provisions. Confederate resistance was light, and Sherman refused to be distracted by minor skirmishes. He pressed forward, precluding the Confederates from disrupting his crossing of the Pearl River, one of the few places where there was a natural line of defense. By February 9, Sherman was in Morton, covering over half the distance from Vicksburg to Meridian in less than a week. By mid- afternoon on February 14, Sherman’s lead elements were in Meridian.

But while Sherman’s march had advanced with great dispatch, General William Sooy Smith’s cavalry advance had not. Sherman had ordered Smith to bring his large force from Memphis southeast in order to arrive at Meridian by February 10, and along the way, to destroy Nathan Bedford Forrest, the Confederate cavalry officer in north Mississippi. Sherman instructed Smith not to be encumbered by “minor objects” but instead to concentrate on destroying bridges, railroads, and “corn not wanted.” Part of Sherman’s own haste to reach Meridian had been motivated by his desire to rendezvous with Smith as planned, but now Smith was nowhere to be found. “It will be a novel thing in war,” Sherman lamented, “if infantry has to wait the motions of cavalry.” But such would be the case.

Smith’s failure to reach Meridian was a source of great frustration for Sherman who wrote that “Smith did not fulfill his orders, which were clear and specific,” but time was not to be wasted. Sherman waited almost a week for Smith, using the time “to wipe the appointed meeting place off the map,” and then departed. In the meantime, Smith had already retreated toward Memphis after a skirmish with Forrest at West Point. That retreat would turn into one of panic after Forrest caught and whipped him soundly in Okolona.

Surprise: attacking the enemy at a time or place he does not expect or in a manner for which he is unprepared.

Sherman would gain much in surprise from the speed of his advance, but he would also employ a series of feints, or deceptive movements, designed to keep General Leonidas Polk, the Confederate commander at Meridian, guessing. In an effort to maintain flexibility against all possible threats, Polk would never be able to concentrate his forces against Sherman’s true attack. To this end, Sherman played on Polk’s fear for the safety of Mobile. Sherman asked Nathaniel Banks, Union commander of the Department of the Gulf at New Orleans, to have “boats maneuvering” in the gulf near Mobile and to “keep up the delusion and prevent the enemy drawing from Mobile a force to strengthen Meridian.” Sherman told Banks he would “be obliged” if Banks would “keep up an irritating foraging or other expedition” in the direction of Mobile to help Sherman “keep up the delusion of an attack on Mobile and the Alabama River.” As Sherman advanced, he fueled this deception himself. He wrote, “I never had the remotest idea of going to Mobile, but had purposely given out that idea to the people of the country, so as to deceive the enemy and divert their attention.”

By threatening Polk with feints, Sherman forced the Confederate commander to keep forces at Mobile that he could have used against Sherman in Meridian. To further add to Polk’s confusion, Sherman sent gunboats and infantry up the Yazoo River “to reconnoiter and divert attention.” The intention was “to make a diversion” and “confuse the enemy.” Then when Sherman departed Clinton on February 5, he divided his command with General James McPherson advancing on Jackson from southwest to northeast while General Stephen Hurlbut marched due east. Polk had more than he could handle.

Polk’s confusion was compounded by a lack of courage to take the initiative and attack Sherman. Instead, Polk merely kept retreating without making any real attempt to confront Sherman. Convinced Sherman was headed for Mobile, Polk left Meridian and took up a position at Demopolis, Alabama, and waited to strike Sherman’s rear.

Sherman’s deception also affected other Confederate commanders. General Joseph E. Johnston feared Sherman was headed for Johnston’s own position at Dalton, Georgia. Rather than reinforcing Polk, Johnston husbanded his forces for an attack that never came. Throughout the Confederate ranks, inactivity, indecision, and confusion reigned.

Sherman called such a tactic “putting the enemy on the horns of a dilemma.” He had helped Grant do this to General John C. Pemberton in the Vicksburg Campaign, and Sherman would do it later in Georgia by keeping the Confederates guessing if his objective was Macon or Augusta, and then if Augusta or Savannah, on his March to the Sea. Sherman achieved the same effect in Mississippi during the Meridian Campaign. The result of this uncertainty was “enemy paralysis and hesitancy” — the objectives of surprise and the key to Sherman’s success.

Concentration: the massing of overwhelming effects of combat power to achieve a single purpose.

In spite of Sherman’s overriding concern for speed, he would not compromise in the size of his force. Sherman’s army consisted of four divisions — two from McPherson’s corps at Vicksburg and two from Hurlbut’s at Memphis — for a total of 20,000 infantry, plus some 5,000 attached cavalry and artillery. Sherman’s adversary Polk could muster a force only half that size and it was widely scattered, with a division each at Canton and Brandon, and cavalry spread between Yazoo City and Jackson.

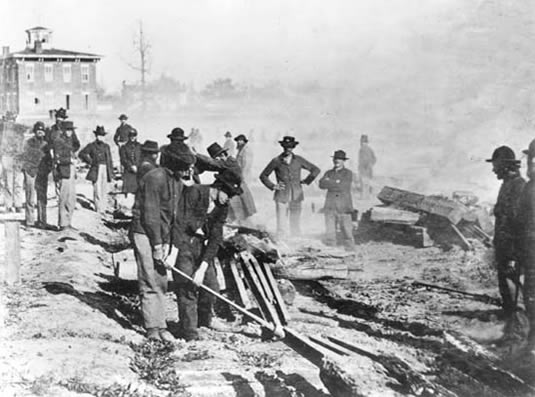

Sherman devoted his forces to the aim to “do the enemy as much damage as possible.” On February 9, his army entered Morton and spent several hours tearing up the railroad track, using the usual method of burning crossties to heat the rails and then bending the hot rails into useless configurations dubbed “Sherman’s neckties.”

At Lake Station on February 11, Sherman destroyed “the railroad buildings, machine-shops, turning-table, several cars, and one locomotive.” But it was after reaching Meridian itself that Sherman unleashed his full fury. For five days he dispersed detachments in four directions with Hurlbut leading the destruction north and east of Meridian, and McPherson focusing on the south and west. For his part, McPherson destroyed 55 miles of railroad, 53 bridges, 6, 075 feet of trestle work, 19 locomotives, 28 steam cars, and 3 steam sawmills. Hurlbut claimed 60 miles of railroad, one locomotive, and 8 bridges. Sherman reported, “10,000 men worked hard and with a will in that work of destruction, with axes, crowbars, and with fire, and I have no hesitation in pronouncing the work as well done. Meridian, with its depots, store-houses, arsenal, hospitals, offices, hotels, and cantonments no longer exists.” His work done, Sherman returned to Vicksburg on February 28.

The Confederates were able to repair their railroads within a month. But the weak Confederate industrial base could not replace the locomotives, and that placed the Confederate forces in a critical situation.

The shape of things to come

Considered in a vacuum, the Meridian Campaign is itself a classic case of the nearly flawless execution of a raid using the four characteristics of offensive operations. But the effects of the Meridian Campaign stretched far beyond the 115 miles of track, 61 bridges, 20 locomotives, and assorted depots, buildings, and structures Sherman laid to waste.

Shelby Foote called Meridian “something of a warm-up, a practice operation in this regard” for what Sherman would execute on a much grander scale in Georgia. More specifically, John Marszalek noted, “When Sherman later contemplated a march to the sea, the important lessons of Meridian were instrumental in his thinking. He could march an army through Confederate territory with impunity and feed it at the expense of the inhabitants. He could wage successful war without having to slaughter thousands of soldiers in the process.” Lawrence Smith cited Meridian as the validation of the strategy of exhaustion that Grant would employ thereafter until the end of the war. Archer Jones agreed that “Sherman’s Meridian raid confirmed the effectiveness of Grant’s new raiding logistic strategy.”

Thus, the Meridian Campaign was an important milestone in the evolution of strategy and the Civil War’s relentless ascent toward total war. Though much less well-known than Sherman’s later March to the Sea, the Meridian Campaign served as a proving ground for the strategy that would ultimately result in Union victory.

Kevin Dougherty is a history instructor at the University of Southern Mississippi, and the author of Civil War Leadership and Mexican War Experience, University Press of Mississippi.

-

Major General William T. Sherman, between 1860 and 1870. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, No. LC-DIG-cwpb-07316. -

Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk, date unknown. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, No. LC-USZ62-79794.

-

Railroads of the Confederacy, 1861. Map courtesy Department of History, United States Military Academy. -

A group of Union soldiers tearing up Confederate railroads, 1864 photograph. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, No. LC-DIG-stereo-1s01398. -

The completeness of Sherman’s destruction and recent urban sprawl have left little to preserve from the Meridian Campaign. One remaining landmark is Merrehope. General Polk used part of the original home as his headquarters, and it was spared by General Sherman. Photograph courtesy Meridian Restorations Foundation, Inc.

Bibliography

Ballard, Michael. Civil War Mississippi: A Guide. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2000

Bearss, Margie. Sherman’s Forgotten Campaign: The Meridian Expedition. Baltimore, Maryland: Gateway Press, Inc., 1987.

Bowman, S. M. and R. B. Irwin. Sherman and His Campaigns: A Military Biography. New York: Charles B. Richardson, 1865

Donald, David. Why the North Won the Civil War. New York: Collier Books, 1962

Flood, Charles. Grant and Sherman: The Friendship that Won the Civil War. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2005

Foster, Buck. Sherman’s Mississippi Campaign. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 2006.

Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative: Fredericksburg to Meridian. Vol 2. New York: Random House, 1963.

Hart, B. H. Liddell. Strategy. New York: New American Library, 1974

Hattaway, Herman and Archer Jones. How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983

Jones, Archer. Civil War Command & Strategy: The Process of Victory and Defeat. New York: The Free Press, a division of Macmillan, Inc.,1992

Marszalek, John. Sherman: A Soldier’s Passion for Order. New York: The Free Press, a division of Macmillan, Inc., 1993

Sherman, William. Memoirs of General William T. Sherman. New York: The Library of America, 1990

United States Department of the Army. Operations, FM 3-0. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, 2001

United States War Department. War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol XXXII. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1900